По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

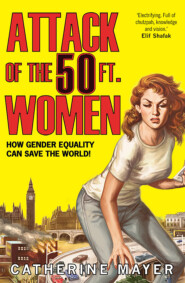

Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: From man-made mess to a better future – the truth about global inequality and how to unleash female potential

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The second category and reason for the ongoing failure to promote women sometimes still dares to speak its name in parties and organisations of the right: hostility towards women. In choosing to fight Conservative MP Philip Davies in the snap election, we highlighted a particularly flamboyant example of this. Davies joined Parliament’s cross-party Women and Equalities Committee and immediately proposed dropping the word ‘women’ from its title. He tried unsuccessfully to derail a bill to ratify the Istanbul Convention, an international accord to tackle violence against women, by filibustering in the hope that the bill would run out of time. On another occasion he gave a speech that inadvertently boosted sales of baked goods. ‘In this day and age the feminist zealots really do want women to have their cake and eat it,’ he declared. Women responded by posting photographs of themselves munching cake.

The left likes to imagine that it is exempt from such wrongheadedness. In reality, misogyny flourishes like knotweed, undermining foundations of parity and respect and periodically breaking into the open, rampant and destructive. The online abuse directed against female MPs who disagree with Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership has been different in degree and content to anything experienced by male dissidents. The invective may not emanate exclusively from the MPs’ left-wing opponents, but could less easily survive in a culture that made serious efforts to stamp out such abuse.

Labour is by no means the only offender. Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the Democratic Presidential nomination unleashed toxic attacks on Hillary Clinton, not by Sanders but by a rump of his followers, so-called Bernie Bros. Two British hard-left parties, the Workers’ Revolutionary Party and the Socialist Workers’ Party, both failed to curb sexual violence in their own ranks. The WRP disbanded after revelations that its leader Gerry Healy had sexually abused female members. The SWP responded to a rape allegation against a senior figure in the organisation by holding a kangaroo court that interrogated the complainant. Had she been drunk? Had she definitely said no?

George Galloway, a former MP who set up the Respect Party after his expulsion from Labour, dismissed rape charges brought in Sweden against Julian Assange. The WikiLeaks founder was guilty, said Galloway, of ‘personal sexual behaviour [that] is sordid, disgusting, and I condemn it’. This was, however, merely ‘bad sexual etiquette’. ‘Not everybody needs to be asked prior to each insertion,’ Galloway added.

In 2016, he campaigned to be Mayor of London. The Women’s Equality Party fielded a mayoral candidate at the same elections, party leader Sophie, together with a London-wide slate of candidates. WE attracted 343,547 votes – a 5.2 per cent vote share and a magnificent result for a first election. (The Green Party’s first electoral outing, at the October 1974 general election, claimed just 0.01 per cent of the vote.) The cherry on our feminist zealots’ cake was Sophie’s performance against Galloway. He started with an advantage as a public figure, a political veteran and one-time star of reality TV show Celebrity Big Brother; he had also presented shows for Iran-backed Press TV and the Russian-funded RT network. Sophie had come to politics as WE’s first leader, just ten months before election day. She outpolled him by almost 100,000 votes.

We celebrated Galloway’s defeat but there was nothing to cheer in the weakness of the British left. Labour performed better than expected in the 2017 snap election, buoyed by an increased youth vote for Jeremy Corbyn and a miserable campaign by the Tories, but still chalked up a third successive loss. The Conservative minority government, reliant on the votes of the socially conservative Northern Irish DUP, continue to tack further to the right.

This bodes ill for women, if not entirely for the reasons set out by traditional left-wing analyses. From the outset, Sandi and I conceived of the Women’s Equality Party as non-partisan. We did so not just because of the serial failures of the left to match deeds to words. Three-quarters of British voters identify themselves as centrists or to the right of centre. We need a chunk of those votes to make change. We want to reach Equalia. We want jam today.

A good starting point is to test a common assumption about women in politics: that women are pragmatic and collaborate across party lines. Academic research supports this view. Analysis of the progress of bills proposed in the US House of Representatives between 1973 and 2008 showed that women in minority parties did better than their male colleagues at keeping their bills alive because they were more adept at garnering support across the aisle.

(The US Senate demonstrated another female strength in January 2016. After a blizzard in Washington DC, women showed up for work. No men slogged through the snow. ‘As we convene this morning, you look around the chamber, the presiding officer is female. All of our parliamentarians are female. Our floor managers are female. All of our pages are female,’ said Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski. ‘Perhaps it speaks to the hardiness of women.’)

My own experience of covering politics encouraged me to believe women might be less inclined to party tribalism. I had seen Westminster women from different parties not only forming alliances in recognition of common goals, but bonding and swapping tips about how to avoid being slapped down or touched up.

Women are diverse but there is always a reservoir of shared experience. The more privileged among us may never truly understand the harsh realities of being doubly or triply disadvantaged by the intersections of race or age or sexuality or gender identity or disability or poverty. We occupy different positions in the kyriarchy – a word coined to describe these intersections and acknowledge the ways in which they enable women to oppress other women – but all of us have found ourselves on the receiving end of the patriarchy. Women of the right may not recognise either expression and are more likely to believe patriarchal structures should be reformed rather than eradicated, but they can be seriously effective in bringing about such reforms as Angela Merkel has shown. Moreover, the impulses of the right increasingly align behind the promotion of women, as the market increasingly recognises the value of women. The later chapter on business explains why that is – and why that recognition isn’t yet matched by equal representation in boardrooms or equal pay at any level.

May’s own record on gender equality was at best a curate’s egg even before her alliance with the DUP. A first tasty morsel came in 2005 with her co-founding of Women2Win, an organisation dedicated to increasing female representation on the Conservative benches. As Home Secretary she introduced new powers to curb domestic abuse, in particular in cases of coercive and controlling behaviour, and then chivvied the police to use these powers. By contrast, her handling of Yarl’s Wood, a detention centre holding women and children pending immigration hearings, was truly rotten. She extended the contract with the private company Serco that runs the facility, despite allegations of sexual violence and other abuses towards its inmates by Serco staff.

Once she became leader, the Conservatives continued to pull further to the right. This probably helped win votes back from UKIP, which was anyway flailing. In entering into a so-called confidence-and-supply arrangement with the DUP, she aligned herself with a party with a history of opposing abortion and LGBT rights.

Regressive social conservatives don’t just try to block progress. They often invoke a future that turns the clocks back: to an age of safety and certainty and homogeneity; to faith in strong leaders who take care of the big stuff.

Such worlds have, of course, never existed, but that makes their pull more potent – and more dangerous. Worlds-that-never-were operate according to laws-that-never-work. Parties of the hard right identify real problems – the competition for scant resources, the democratic deficits created by globalisation, and religious extremism and misogyny dressed up as ‘cultural practice’ – but proposes responses that will make everything worse: xenophobia and a retreat into isolation. Often the nostalgia invokes a natural order threatened by the forces of social change – and that supposed natural order never turns out well for women. Beata Szydło’s Law and Justice Party in Poland has cut state funding for IVF treatment, tightened the availability of contraception and only backed away from a total ban on abortion, even in cases of rape, after mass protests. Some hard rightists allow themselves to imagine that a lack of contraception or access to abortion will encourage young couples to marry. Some hard rightists seem to believe that hostility towards homosexuality will make it go away.

The hard right also routinely mistakes feminism for the cause of bad relations between the sexes, rather than recognising feminism as a response and solution to the conflict. Even so, parties of the hard right are often led by women. Frauke Petry – like Merkel, a former chemist who grew up in East Germany – led Germany’s Alternativ für Deutschland to its biggest successes, entry into five state parliaments in 2016 and in Saschen-Anhalt an astonishing 24.3% of the vote. Pia Kjærsgaard, co-founder and former leader of the Danish People’s Party, moved on to become the Speaker of Denmark’s Parliament and a prominent critic of multiculturalism. Siv Jensen has brought Norway’s Progress Party into government for the first time, in coalition with Erna Solberg’s Conservatives. Jensen, who serves as Finance Minister, has moderated her anti-Islam rhetoric since taking office but opposes her own coalition’s agreement to expand the numbers of Syrian refugees it accepts.

That women rise in such parties is a reflection of the fractious nature of such groups – remember: crises create room for movement – but the hard right has also got wise to the way a female face can lend an air of friendly modernity to their movements. They draw inspiration from a prominent role model. In 2011 Marine Le Pen took control of France’s Front National from its founder, her father Jean-Marie, and four years later oversaw his expulsion from the party after he downplayed the Holocaust as ‘a detail of history’. Under her stewardship the party has flourished, successfully expanding its reach to voters who shied away from its original incarnation. Her slicker, friendlier Front National sublimates its racism into messaging linking immigration to Islamism and an increased threat of terrorism. Regional elections in 2015 saw it come first in the opening round of voting with 28 per cent. She and her niece Marion Maréchal-Le Pen both won more than 40 per cent in their contests. For a time, it looked as if Le Pen might beat that score in her 2017 race for the Élysée Palace. She trounced traditional conservatives and old-style leftists in the first round, but lost out in the second to the only candidate who could also present himself as a political outsider, Emmanuel Macron, leader of En Marche!, a party he’d founded only a year earlier.

Le Pen reinforces the warning against expecting of female leaders a more compassionate politics. Yet she also illustrates strong arguments for prising open political clubs to admit more women. For one thing, traditional politics has been weakened precisely because it operates clubs. If mainstream parties had kept closer touch with voters, they might have done a better job of answering the real concerns of those voters. Instead they’ve created space for demagogues to masquerade as truth-tellers and champions of the working man (if more rarely of the working woman).

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: