По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

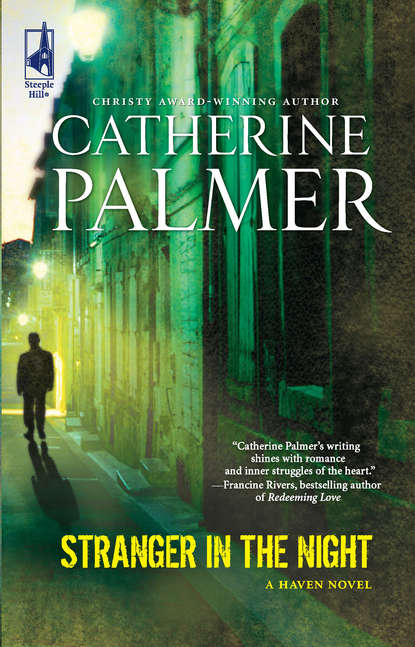

Stranger In The Night

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“A Scot. I’m Irish.”

“American, actually.” She pulled her hand away and stuck it in the pocket of her slacks. “So, Semper Fi and all that. I appreciate the interest you’ve taken in these people, Sergeant, but Refugee Hope is accountable only for the families we relocate. If you’re responsible for this group, you’ll have to—”

“Semper Fi and all that?” He leaned forward, as if he weren’t sure he heard her correctly.

Oh, great, Liz thought. She picked up her flask, unscrewed the lid and poured the third cup. Praying he couldn’t see her hand trembling, she lifted the mug to her lips. The tea slid down her throat.

This was not what she needed a few minutes after eight in the morning. Not an overwhelming, overbearing, overly handsome sergeant with a death grip. And certainly not a pair of striking blue eyes that never seemed to blink.

“Sergeant Duff.” She found a smile and hoped it looked sincere. “Please forgive my lack of courtesy. I have a large number of families in my caseload. An overwhelming number. This group isn’t among them.”

With effort, she dragged her focus from the man’s sculpted cheekbones and clean-shaven square jaw. The group huddled under his protection shrank into each other as she assessed them. A man, midforties, she guessed. His wife, hard to tell her age behind those big glasses, clearly traumatized. Two children. The girl, about seven, needing new clothes. The boy, probably five, missing several front teeth.

“This is Reverend Stephen Rudi,” Sergeant Duff said, clamping his big hand on the man’s shoulder. “His wife, Mary. Their children, Charity and Virtue. They’re from Paganda.”

Paganda. Images flashed into Liz’s mind. Photographs she’d seen. Villages burning. Mass graves. Boy soldiers toting machine guns. She thought of the people she had met in Congo. They spoke of Paganda in hushed tones. Even worse than most places, they said. Genocide. A bloodbath.

Liz shuddered and sized up the little family more closely. Who knew what these people had endured? Too often these days, she caught herself regarding the refugees as line items on one of her many lists. Family from Burundi: mother, father, eight children. Family from Bosnia: mother, her brother, four children. Family from Ivory Coast: mother (pregnant), father, six children.

When had they ceased to be human beings?

“Reverend Rudi, good morning.” Liz offered her welcome in the African way—right hand extended, left hand placed on the opposite arm near the crook of the elbow. A demonstration of honor, as if to say, “I will not greet you with one hand and stab you with the other.”

The man stepped forward, shook her hand and made a little bow. “Good morning, madam. Thank you very much for your time. My family is in great need of assistance.”

How often had she heard these words, Liz wondered. The need was a pit, bottomless and gaping. A hungry mouth, never sated.

“Which agency brought you to St. Louis?” she asked him. It was a relief to turn her attention from Sergeant Duff. Like a male lion poised to spring, the man didn’t budge. His presence filled the cubicle with a sort of expectant energy Liz could hardly ignore.

Reverend Rudi’s voice was strained but warm, carrying familiar ministerial overtones. “Madam, Global Care brought my family from a refugee camp in Kenya. We traveled by airplane from Nairobi to Atlanta. My wife’s brother invited us to St. Louis.”

“Global Care doesn’t have an office here,” Duff inserted. “The Rudis will need your help.”

Liz returned her focus to his face. The man had moved closer to her desk now, his fingertips touching her stack of files, his shoulder tilted in her direction.

“I’m sorry, Sergeant. As I said before, if Refugee Hope didn’t bring this family to the States, we won’t be able to provide assistance. The Rudis need to contact Global Care in Atlanta and make arrangements.”

“But as you see, they’re here now. So what can you do for them?”

“Nothing. I’m authorized to work only with my families. Those brought in by Refugee Hope.”

“So transfer them.”

She studied the blue eyes. He really did expect her to obey. He thought she would capitulate right on the spot. The man was used to giving orders, and to having them followed.

Liz had never done well with authority figures. She simply didn’t buckle.

“If Global Care wants to make provisions for this family,” she informed him, “you will need to speak to someone at their headquarters in Atlanta. Refugee Hope is based in Washington, D. C. St. Louis is a resettlement point. We follow our agency’s rules.”

Joshua Duff straightened. His eyes narrowed. Then he turned to the family. “Pastor Stephen, how about you go find a snack machine and get the kids something to eat.”

He fished a wallet from his pocket. Liz tried not to gawk at an accordion of cash that unfolded when he opened it. He removed several bills and held them out. The African minister took the money with some reluctance. Duff misunderstood.

“Snack machine.” He motioned as if he were pushing buttons with his index finger. “Food. Candy bars. Crackers.”

With a nod, Reverend Rudi shepherded his little flock out of the cubicle. The moment they were out of sight, Duff leaned into her desk.

“Listen, ma’am, I came across this family last night. I agreed to help them. You work for a refugee agency, right? These are refugees. So do your job.”

Liz stepped around her desk. “This is not the Marine Corps, Sergeant. But we do have a protocol and you’re asking me to violate it. I will not do that.”

The dark eyebrows lifted. “All right, I understand. So, what do we have to do to make this happen?”

“I’ve told you. Call Global Care and turn the family over to them.”

“And where is that pitiful bunch supposed to go while the agency figures out what to do with them?”

“You could put them on a bus and send them back to Atlanta.”

“They don’t want to live in Atlanta. They want to stay here and look for the lady’s brother.” He set one hip on her desk, bringing himself down to her eye level. “Ms. Wallace, you wouldn’t be working for this agency if you didn’t have compassion. These folks need a place to stay, decent jobs, a way to get around. That’s what you do, isn’t it? Why don’t you just help them out of the goodness of your heart?”

“Why don’t you? ”

“Because I live in Texas.”

He looked away, the muscle in his jaw flickering. Liz could see the man was struggling for control. Good. She had a full day of work ahead, and she didn’t like being pushed around.

In a moment, he faced her again. “Look, I’ve just spent seven months hunting insurgents in the Afghan mountains. My third deployment. I’m tired. My patience—never a strong suit—is wearing real thin right now. I came to St. Louis to visit a friend for a couple of days, and this morning he sent me out on a little mercy mission on behalf of Reverend Rudi and his family. Now, they’re nice folks, and they’ve been through an ordeal worse than most. I believe you know exactly how to arrange a happy American life for them, ma’am. Am I wrong about that?”

“I know how to resettle refugees, yes. But as I said, I’m not allowed to work with families who aren’t on my list. If you’re so worried, you help them. It’s time-consuming but not all that complicated. I’ll tell you what to do step by step. How does that sound?”

He bent his head and chuckled. “Well, well, well. You know something, Liz Wallace? You’re more trouble than a couple of Pashtuns haggling over the price of a camel. I can handle them. I can track a sniper across five miles of bare rock. I can even talk a sheikh into turning loose a few goats to feed some hungry beggars. But I can’t seem to get a social worker to help a family of refugees. Did I catch you on a bad day, or are you always this mean?”

Liz rolled her eyes. “Move. You’ve got your Duff on my files, Sergeant.”

With a laugh of disbelief, he stood. Liz scooped up her paperwork and flipped open the first file.

“You see this family?” she said, covering the name with her thumb. The photographs of four Somalis were lined up along one side. They looked like criminals posing for mug shots.

“This mother was raped by guerrilla soldiers. Seven of them. In front of her husband and children. They killed the father, the baby and the other two youngest of her five kids. Chopped them up with machetes. They took the oldest girl, raped her, tied her legs and arms together and then threw her into the back of their truck. They took the oldest boy as a slave. Then they drove away.”

She paused and glanced at Duff. His grim expression told Liz she was getting through.

“The mother never saw her children again,” she continued. “She was left with one daughter, a thirteen-year-old who had been fetching water from a stream when the rebels attacked. This woman and her daughter walked more than a hundred miles across the Somali desert into Kenya. They lived in a mud hut inside a United Nations refugee camp for five years. They ate gruel and got water from a spigot that served twenty other families. Both gave birth to sons. This mother, her daughter, son and grandson are here now. In St. Louis. Are you with me, Sergeant?”

“All the way.”

“Shall I continue?”