По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

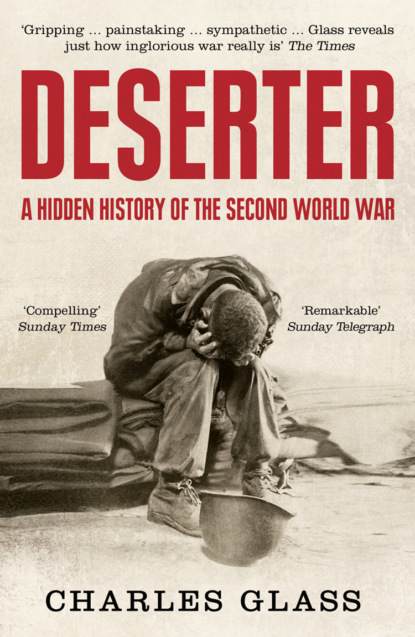

Deserter: The Last Untold Story of the Second World War

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

b. They feign physical and mental illness.

c. They hide out for days to avoid being placed on an overseas shipment list.

d. They go AWOL in order to stand trial and be confined.

e. They dispose of clothing and equipment.

f. They throw away their identification tags.

g. They answer for absentees on roll call.

h. When an officer approaches the area, the word is passed along and they dash for the woods through windows and doors, even jumping from upstairs screened windows, taking the screens with them.

General Cooke extended his mission to Camp Edwards on Cape Cod, where 2,800 soldiers who had deserted in the eastern United States were imprisoned. (Deserters west of the Mississippi went to a similar prison in California.) Cooke asked the camp’s commandant how long the men remained behind bars. ‘As long as it takes to find out who they are and what outfit they belong to,’ he said. ‘Then we take them under guard and put them on a ship.’ When trainees broke their spectacles or false teeth to avoid shipping out, the army changed the regulations so they could be sent to battle without them. Many went into hiding. The commandant said, ‘We’ve dug them out of bins under the coal and rooted them out of caves and tunnels dug underneath their barracks.’ Camp guards resorted to confining deserters in special compounds without explanation a few hours before putting them on trains for embarkation ports. Cooke asked whether any men tried to bolt outside the camp. ‘Only when they’re being taken to the port. Then they’ll jump out of windows, off of moving trucks and even over the sides of harbor boats.’ The army name for it was ‘gangplank fever’.

Cooke spoke to the prisoners. Some had family worries that they had to deal with before they could leave the United States. One soldier said he could not abandon his wife, who was pregnant and sick. Others told him: ‘I can’t fire a gun or go under fire.’ ‘I can’t kill anyone, I don’t believe in killing people.’ ‘I was afraid, I guess, so I went home.’ ‘I wanted to see my girl; I don’t like the Army and I’m scared of water.’

From Fort Meade, Steve Weiss, Sheldon Wohlwerth and the other graduate trainees went to Newport News to board ships. None of them knew their destination or their future divisions and regiments. As infantry ‘replacements’, they would fill positions left in the ranks by men who had been killed, captured, disabled physically or mentally or were missing in action. Some of the battlefield missing, about whom no one spoke, had gone ‘over the hill’, deserting the army with no intention of returning. As the replacements neared the Straits of Gibraltar aboard troop transports that were prey to German U-boats, a rumour circulated that they were bound for a place they had never heard of, Oran. The French Algerian port town, occupied by the Americans and British since November 1942, had become the US Mediterranean Base Section and theatre supply depot. A few of the replacements were so sure Oran was Iran that they lost a month’s pay betting on it.

Brigadier General Elliot D. Cooke had beaten Weiss to North Africa, where he continued his research into the high rate of desertions and nervous breakdowns. He asked a nineteen-year-old corporal, Robert Green, if he had been afraid when the patrol he was leading ran into the Germans. ‘Yes, sir, I was scared all right! Anybody tells you he isn’t scared up front is just a plain liar.’ Cooke probed the young soldier about men who ‘cracked up’. He answered, ‘Some of them do. But you can see it comin’ on, and sometimes the other guys help out.’ Cooke asked how he could see it ‘coming on’. Green said they became ‘trigger happy’:

They go running all over the place lookin’ for something to shoot at. Then, the next thing you know they got the battle jitters. They jump if you light a match and go diving for cover if someone bounces a tin hat off a rock. Any kind of a sudden noise and you can just about see them let out a mental scream to themselves. When they get that way, you might just as well cross them off the roster because they aren’t going to be any more use to the outfit.

Cooke wondered how to help such men, and Green answered,

Aw, you can cover up for a guy like that before he’s completely gone. He can be sent back to get ammo or something. You know and he knows he’s gonna stay out of sight for a while, but you don’t let on, see? Then he can pretend to himself he’s got a reason for being back there and he still has his pride. Maybe he even gets his nerve back for the next time. But if he ever admits openly that he’s runnin’ away, he’s through!

In Algiers, a senior officer told Cooke, ‘If a soldier contracts a severe case of dysentery from drinking impure water, his commander feels sorry for him and is glad to see the man sent to a hospital. But if the soldier becomes afflicted with an equivalent ailment from stress and strain, that same commander becomes incensed and wants the soldier court-martialed.’

General Cooke wryly proposed a cure, ‘Then the only remedy is to eliminate fear.’

After two weeks in a camp near Oran, Steve Weiss and eighty-nine other replacements from Fort Meade boarded a converted British passenger liner, the Strathnaver, for the four-day cruise to Naples. The Allies had conquered Naples on 1 October 1943. By May 1944, when Weiss arrived, the Allied armies, the Mafia and the Allied deserters who controlled the black market in military supplies jointly ran the city. Thousands of soldiers were enriching themselves at army expense, stealing and selling Allied supplies. Some Italian-Americans had deserted to drive trucks of contraband for American Mafia boss Vito Genovese. Other deserters had joined armed bands in the hills, robbing both the Allies and Italian civilians. Reynolds Packard, the United Press correspondent who had lived in Italy before the war and returned on the first day of the invasion, wrote,

Within a few weeks Naples became the crime center of liberated Italy. And the word ‘liberated’ became a dirty joke. It meant to both the Italians and the invaders that an Allied military government got something for nothing: such as an Italian’s wife or a bottle of brandy he took from an intimidated bartender without paying for it. Prostitution, black marketing, racketeering, and confidence games were rampant … It was a mixed-up circle. The GIs were selling cigarettes to the Italians, who in turn would sell them back to the Americans who had run out of them. But the main trade was trafficking in women.

Norman Lewis, an Italian-speaking British intelligence officer in Naples, noted the same phenomenon: ‘Complaints are coming in about looting by Allied troops. The officers in this war have shown themselves to be much abler at this kind of thing than the other ranks.’ The officers were both American and British, some of whom had sent looted artworks back to England on Royal Navy ships. When Lewis investigated corruption in Naples, the black marketeers’ influential friends blocked him. He wrote,

One soon finds that however many underlings are arrested – and sent away these days for long terms of imprisonment – those who employ them are beyond the reach of the law. At the head of the AMG [American Military Government] is Colonel Charles Poletti, and working with him is Vito Genovese, once head of the American Mafia, now become his adviser. Genovese was born in a village near Naples, and has remained in close contact with its underworld, and it is clear that many of the Mafia-Camorra sindacos [mayors] who have been appointed in the surrounding towns are his nominees … Yet nothing is done.

Army gossip about these activities circulated among the troops, some of whom believed that the officers’ behaviour justified their own acts of theft or extortion. Steve Weiss, as yet unaware of the war’s seamier side, saw the Italian campaign in terms of his father’s experiences of the First World War. The cargo wagons on the train he took from Naples to Caserta were just like the ‘previous war’s forty men and eight horses’.

At Caserta, the new GIs were stationed at the Replacement Depot (which they called the ‘repple depot’ or ‘repple depple’), near the palatial headquarters of the 5th Army Group under British Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander. The former royal palace was also home to Allied press correspondents. One of the best, Australian Alan Moorehead of the British Daily Express, thought the headquarters ‘a vast and ugly palace’, even if it was more commodious than the GIs’ tents. ‘Unlike the field marshal,’ Weiss wrote, ‘we at the “repple depot” were herded together like cattle, waiting for assignment to any one of a number of infantry divisions fighting across the Italian peninsula. I was adrift, alone and friendless, as usual, in a sea of olive drab, feeling more like a living spare part.’ For two weeks in May, the young soldiers had nothing to do while the army decided where to put them. At the end of the month, a sergeant called out the names of ninety soldiers for posting to the 36th Infantry Division at Anzio. Among them were two trainees from Fort Blanding, Privates Second Class Sheldon Wohlwerth and Stephen J. Weiss.

The 36th was a Texas National Guard division that had come under federal control in November 1940, whose men wore the Texas T, like a cattle brand, on their left shoulders. The commanding officer of the ‘T-Patchers’ was Major General Fred Livingood Walker, a First World War veteran with a Distinguished Service Cross for exceptional gallantry and a strong supporter of his troops. Ohio-born Walker had assumed command of the Texas division in 1941.

War for the 36th began with the first American landing on the European continent at the Bay of Salerno in southern Italy on 9 September 1943. German artillery dug into the Roman ruins at Paestum hit the invaders hard, pinning down one battalion of the 36th Division’s 141st Regiment on the beach for twelve hours. The Texans pushed inland to launch a frontal assault on Wehrmacht units in the village of Altavilla. Misdirected American artillery, however, halted their advance and forced the men to scramble for shelter in the brush. When they eventually conquered the village, a German detachment moved onto a summit above to batter Altavilla with artillery. The 36th withdrew, momentarily exposing its divisional headquarters to a German onslaught. Assisted by hastily armed rear echelon cooks, typists and orderlies, the 36th retook Altavilla and secured the southern portion of the beachhead. The Salerno invasion cost the 15,000-man division more than 1,900 dead, wounded and missing.

As murderous as their first few days in Italy proved, the Texans soon suffered worse. When the Wehrmacht poured in reinforcements from the north, the counter-offensive hit the 36th head-on. The division suffered another 1,400 casualties while taking San Pietro, a key village in the Liri Valley on the route to Rome, in December. In January, Fifth Army commander General Mark Clark ordered General Walker to send his division across the Rapido River as part of an operation to break out of the Salerno beachhead. It was nothing less than a suicide mission. The fast flowing river at that time of year measured between twenty-five and fifty feet wide and around twelve feet deep, not an insurmountable obstacle. However, other factors militated against a successful crossing. Winter rain made the current both fast and powerful. The river’s wide, muddy flood plain was impassable to trucks, forcing the men to carry boats to the bank. The Germans had planted a dense field of landmines, and they positioned heavy artillery on the heights beyond the river’s west bank. General Walker opposed the operation, but he obeyed Clark’s orders. His men, as he feared, were slaughtered during three attempted crossings. Those who made it to the other side fought without air or armour support. Lacking communication with the friendly shore, they ran out of ammunition and were driven back by German artillery. The two-day ‘battle of guts’ ended on 22 January with 2,019 officers and men lost – 934 wounded, the rest killed or missing in action. Some of the missing had drowned, and their bodies were swept downstream. General Walker wrote in his diary after the Rapido failure, ‘My fine division is wrecked.’ Raleigh Trevelyan, a twenty-year-old British platoon commander in Italy, summed up the 36th’s resulting reputation, ‘The 36th had, frankly, come to be looked down on by the other divisions of the Fifth Army. It was considered not only to be a “hard luck outfit”, but trigger happy.’

In eleven months of Italian fighting, the division lost 11,000 men. Only 4,000 thousand of the original cadre remained, the rest having been replaced by inexperienced young recruits like Steve Weiss. When Weiss arrived in Italy in May 1944, there were few less hospitable divisions than the war-drained 36th and no more dangerous place than the Anzio beachhead. In his memoirs, General Clark called Anzio a ‘flat and barren little strip of Hell’. British platoon commander Trevelyan wrote that ‘nowhere in the Beachhead was safe from bombs or shells’. Even the naval shore craft, the only means of supplying the troops from the rear area at Naples, were subject to German fire.

Only thirty miles from Rome, the beaches had been peacetime resorts with first class hotels, restaurants, cafés and ice-cream shops. Allied bombardment of Anzio and Nettuno before the landing, intended as an end run north of Salerno that would ease the advance to Rome, emptied both towns of most of their inhabitants. The Anzio invasion began at two o’clock on the morning of 22 January 1944, when the US 3rd Infantry Division hit the undefended beach and British commandos and American Ranger units took control of the surrounding area. As with the landing at Salerno, early success was undermined by the Allies’ failure to take advantage of weak German defences by pushing quickly inland. The Germans thus had time to regroup and counter-attack. By May 1944, when Private Steve Weiss and the other replacements arrived to fill the ranks of the badly depleted 36th Division, the Allies were still dug in on the exposed beachhead.

The first soldiers Weiss encountered were barricaded in a makeshift stockade of wood and barbed wire. The fifty dishevelled troops were not German prisoners of war, but, to Weiss’s astonishment, Americans. ‘Under armed military police guard, some of the prisoners seemed very weary and disoriented, like vagrants down on their heels and luck,’ Weiss wrote. ‘Others, more aggressive than the others, threatened and hurled obscenities at us, warning, with pointed finger or clenched fist, we’d end up like them, misunderstood and deserted by the army.’ The army, though, had not deserted these men. They had deserted the army.

Raleigh Trevelyan, the British platoon commander who spent months at Anzio, wrote that not all deserters were in the stockade: ‘There were said to be three hundred deserters, both British and American, at large on the Beachhead. At first nobody made out where they could hide themselves in such a small area.’ Another British officer, Lord John Hope of the Scots Guards, was bird-watching in some deserted gardens east of Nettuno, when he uncovered a cache of canned food under a pile of wood. He told Trevelyan:

I turned a corner and was confronted by two unshaven GIs, one with a red beard, with rifles. I knew it was touch and go. ‘What are you doing here?’ one of them asked. I showed him my British badges, and when I said I was bird-watching they burst out laughing. They pretended they were just back from the front.

Hope reported the deserters to the American Provost Marshal, who sent MPs in a jeep with Hope on the hood to show the way. They found the deserters, who, in Hope’s words, ‘jumped up and ran like hell into a tobacco field; the men in the jeep belted off into the crops … No expedition was organized to go into the bushes to find out who was there. Men just couldn’t be spared.’

United Press correspondent Reynolds Packard came across another deserter near Anzio. The American soldier had no rifle, a court martial offence. Packard asked where it was. ‘Fuck it,’ the GI said. ‘I threw it away. I’ve quit fighting this goddamn war.’ Packard told his jeep driver to hold the deserter while he searched for the missing weapon. He found it and gave it to the soldier, who threw it away again. ‘Fuck this war,’ he said. ‘I’m not fighting anymore.’ Packard decided to take him to division headquarters:

Just before we got there, I hauled off and hit him, knocking him unconscious.

‘What the hell are you doing?’ my driver, Sergeant Delmar Richardson, asked. ‘Gone nuts?’

‘I don’t want to take him into a hospital while he’s talking about not fighting this fucking war anymore. That’s all.’

The deserters in the Anzio beach stockade, like sentries at the inferno’s gates, persisted in their warnings to Weiss and the other arrivals. The replacements endured the abuse, until trucks pulled up to take them away. They drove through Anzio town, most of it destroyed by Allied and then German bombardment, to a hill above the beach. There they made camp for the night.

In the morning, Steve Weiss attended the Catholic chaplain’s outdoor Mass. He then went to find his friend from Fort Meade, Hal Sedloff. Sedloff had been posted to the 45th ‘Thunderbird’ Infantry Division, composed of National Guard units from Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico. The 45th had fought as part of General George Patton’s Seventh Army in Sicily the previous July, took the beach at Salerno in September and landed at Anzio in January 1944. Although Sedloff went into the line with the 45th as it fought its way north to Rome, Weiss discovered he was still near Anzio in a field hospital. A nurse there told Weiss that Sedloff had taken part in two battles, but he had been incapable of fighting due to ‘night blindness’. His wounds were not physical. Weiss did not understand. The nurse explained that he had ‘battle fatigue’, a term Weiss heard for the first time. In his father’s war in 1918, they called it ‘shell shock’. Army psychiatrists had begun using the term ‘psychoneurosis’, while the British preferred ‘battle exhaustion’ with its implication that rest could cure it. The nurse whispered to Weiss, ‘No one is immune.’ Weiss was unaware that, by this stage of the war, a quarter of all combat casualties were psychiatric.

Deciding that Sedloff’s trauma made him a risk to a combat unit, medical staff recommended him for rear echelon duty. This was a discreet and humane way to retain the services of men rendered unfit for combat. One battalion officer, after relieving a veteran from further frontline duty, explained, ‘It is my opinion, through observation, that he has reached the end of endurance as a combat soldier. Therefore, in recognition of a job well done I recommend that this soldier be released from combat duty and be reclassified in another capacity.’ Weiss, who guessed that Hal Sedloff cracked because he still missed his wife and daughter, left the hospital without being allowed to see his friend.

‘I thought Hal, at twenty-eight, was someone to depend on, because of his age and experience,’ Weiss wrote. ‘I was chilled by the prospect of carrying on, alone, without the support of and belief in some kind of father figure.’

Weiss’s initiation into the war zone had been a beach stockade filled with men who ran from battle and an older friend comatose with fear. Neither increased his confidence in himself or the army. Aged 18 without someone to trust, he questioned his capacity to measure up under fire. A study of American combatants had found that 36 per cent of men facing battle for the first time were more afraid of ‘being a coward’ than of being wounded. Weiss needed an experienced commander to show the way, but officers and non-commissioned officers did not survive much longer on the line than enlisted men. Many were replacements themselves, without time to become acquainted with soldiers under their command. The replacement system, as the army was beginning to realize, undermined morale. Weiss did not know that, not yet.

The system in earlier conflicts withdrew whole regiments or divisions from battle to absorb replacements during re-training. This permitted new soldiers to know their officers and their squad-mates. General George C. Marshall, the US Army Chief of Staff, had initiated a policy of replacing individual soldiers within each division without pulling them back from the front. Marshall explained, ‘In past wars it had been the accepted practice to organize as many divisions as manpower resources would permit, fight those divisions until casualties had reduced them to bare skeletons, then withdraw them from the line and rebuild them in a rear area … The system we adopted for this war involved a flow of individual replacements from training centers to the divisions so they would be constantly at full strength.’ The First World War’s 30,000-man divisions had been cut in half for the Second, and divisional losses in combat left many with a majority of troops who did not know one another. Marshall concluded, ‘If his [an army commander’s] divisions are fewer in number but maintained at full strength, the power for attack continues while the logistical problems are greatly simplified.’ Logistics were simpler, but group loyalty evaporated.

In the evening after Weiss’s attempt to visit Hal Sedloff, Luftwaffe planes breached the Anzio defences and bombed the beachhead. Steve Weiss watched five German HE-111 medium bombers soar only 500 feet above him. Ground fire, he wrote, was ‘erratic, no spirited defense here’. Why weren’t the anti-aircraft batteries doing their job? The planes hit several targets, including an American ammunition depot, and flew away untouched. Weiss felt that American soldiers were unsafe everywhere, even on a beachhead that had been established four months before. How much worse would it be in the hills where the 36th Division was face to face with the Germans? Ordnance from the ammo dump exploded and burned all night, its unnatural light reminding Weiss of the war his father never told him about.

EIGHT (#u37e40da0-1303-54c8-9430-5cf02a79a713)

They enlisted in a condition almost like drunkenness and some woke up to find themselves under arms and with a headache.

Psychology for the Fighting Man, p. 306

A CACOPHONY OF TIN WHISTLES and shouts from the prison yard woke SUS John Bain from the refuge of sleep. His eyes adjusted gradually to dawn trickling through three small windows set high in the wall opposite his cell door. On this first morning at the Mustafa Barracks, he experienced a double awakening: to the curses and groans of his eight fellow prisoners and to ‘a drench of pure horror as the full knowledge of his circumstances drove like a bayonet to the gut’. Sight and sound disturbed him less than the smell of ‘unclean bodies and bodies’ waste, the reek of disgrace and captivity’.

Staff Sergeant Pickering unbolted the door. The nine prisoners snapped to attention, grasping their ‘chocolate pots’. Pickering ordered them to the latrines to ‘slop out’ the pots, back to the cell to fetch their wash bags and double-time outside again. Pressing their faces to a wall, they waited for Pickering to bring a tray of razors. The used blades were so blunt that Bain cut his cheek. A staff sergeant whom Bain had not seen the day before relieved Pickering: ‘The NCO advancing towards them across the square was short, not a great deal over five and a half feet, but he looked powerful, his shoulders wide and the exposed forearms thick and muscular. He had a neat dark moustache and his eyes were small and very bright, like berries.’ He was Staff Sergeant Brown.

Under the barking of Brown’s commands, the SUSs marched, double-time, to the storehouse for buckets and brushes. For an hour on hands and knees, they scrubbed the barrack square. With that completed, they carried their mess tins to the cookhouse. Kitchen workers filled half of each tin with congealed porridge and bread, the other half with tea. The SUSs rushed back to their cell, inevitably spilling tea, to eat. Next came Physical Training, which veteran inmates called Physical Torture.

Under a cloudless African sky, Staff Sergeant Henderson directed standard military calisthenics: jumps, bends, push-ups and sit-ups. Wearing full combat uniform, including heavy boots, in heat over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the men tired more rapidly than during the toughest training in Britain.

Sweat flowed within seconds. In minutes, the men were winded. When one collapsed onto the sand, Henderson kicked his ribs to get him back up. The men were ‘gasping for air like stranded fish and trying desperately and ineffectually to press their bodies clear of the ground’. Then, along with another two hundred or so inmates in the square, they halted.