По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

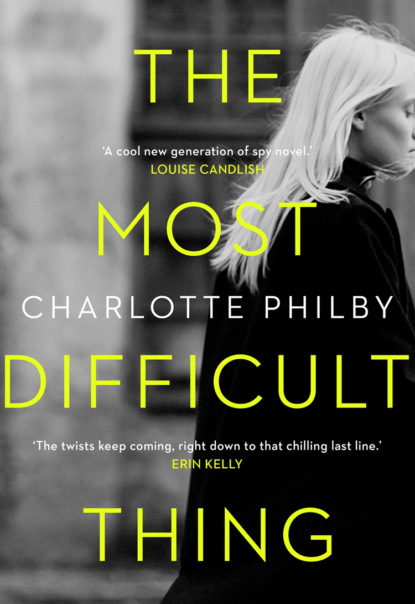

The Most Difficult Thing

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The only thing that was out of place was a single box of condoms, which he had gone to lengths to dig out; his ability to think so cautiously, even in the heat of the moment, pricked at me once it was over. At that moment, entangled in his arms, I would have risked anything never to let him go; it was the first clue, if only I had been willing to see it, as to how uneven the balance of power between us was.

‘Must be a reaction against my house, growing up,’ Harry said, watching my eyes react to the sparseness of it all, the precision. It was the first time he had mentioned his childhood and I stayed silent, willing him to carry on.

We were moving through to the living room now, my eyes scanning the original fireplace, unused; just a few books neatly stacked over purpose-built shelves. Hungrily, I drank in any detail I could latch my eyes upon.

Comparing the scene before me with the image of the flat I had created in my mind, I found my imagined version already slipping away.

‘When you’re one of six and there are other people’s things everywhere, I suppose a kind of efficiency grows out of craving your own personal space,’ Harry said.

I thought of the silence of my parents’ house, the endless space.

‘You grew up in Ireland, right?’

‘Galway.’ He turned to the door, the look passing over his face telling me he’d had enough of this kind of talk, and I was happy to follow him back to safer ground. Any question I asked him was liable, after all, to be turned back on me.

‘And this is my bedroom.’

Harry had moved across the hall and was standing in the doorway of the final room. There was a small double bed against one wall, a desk against the other, piled high with papers.

His eyes followed mine, over the bed, which was low to the ground, the sheets white and nondescript. Beside it, on stripped wooden floorboards, there was a square alarm clock and a notebook. Nothing else to betray the details of a life.

Moving towards the desk, my eyes trailed the papers neatly covering the surface.

‘So, what is it you’re working on?’

He moved to intercept me, pulling me towards him as I reached the desk.

‘If I told you that, I’d have to kill you.’

There was something so powerful about him, so far beyond my reach. And yet the truth was we weren’t so different, he and I. For all his bravado, for all his success. People like David, their lives were defined by what they had; Harry’s life, like mine, was defined by what he had lost.

‘It was a Saturday morning,’ Harry confided one night, our noses pressed together in the darkness of his flat, the occasional flash of a car headlight through the bedroom window the only sign that in this moment we weren’t the only two people left on Earth.

‘I’d been moaning on and on about a toy car I wanted. Little red thing I’d seen in the window in town a couple of days earlier. Wouldn’t quit. In the end, my pa says, “If it’ll shut you up, I’ll get you the damn car.” He walked out the house, and that was it. Ten minutes later, he lost control of the steering wheel and … Three people died.’

There was a pause and I felt the pain that moved across his face.

‘Oh, Harry.’ I moved so close to him that I could feel the muscles in his body contract with grief.

‘It was my fault.’ His voice was so quiet, but I felt the tears soaking into my scalp. ‘You can’t imagine what that’s like. To know—’

‘That was not your fault, Harry, don’t you ever think that.’ I clung him, hushing his cries with my own, as if soothing my younger self.

I squeezed him harder then, feeling my own confession pour from my lips; the relief of saying the words out loud tinged with fear. Our secrets reaching out for one another, their grip so tight I could hardly breathe.

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_ee1f5ae0-8f79-5459-aa7d-0f12eb5cc24d)

Anna (#ulink_ee1f5ae0-8f79-5459-aa7d-0f12eb5cc24d)

If it had happened a few months earlier, I would have told Meg about Harry and me, regardless of what I had promised. How different things might have turned out if I had. There was nothing she and I did not share, back then, nothing we wouldn’t have told each other, until suddenly there was.

At first I put the cracks that began to show in Meg’s armour down to the pressures of office life – the spikiness that had always been offset by a natural generosity and easy humour falling away into something that would have been otherwise unexplainable.

David had picked up on it too, on the occasions when we still found time to hang out together, the three of us, between the various pulls of our respective working lives. He had tried to raise it with me but I had played the ignorant, telling myself I would not discuss Meg behind her back but knowing deep down that I just did not want to think about it.

And then, one day, the blinkers were torn off.

I was sitting at the table in the kitchen of our flat, typing up a piece on monochrome accenting. Behind me, a single panel of wall was lined incongruously with illustrations of botanical branches: a single roll of statement wallpaper which I had plucked from a box of samples at the office, with Clarissa’s encouragement; one of a number of disjointed acquisitions with which I had started to embellish the flat over the past months. I was squinting at the computer, trying to block out the churn of Camden High Street filtering in through the sash, when Meg walked through the front door, slamming her keys onto the counter, pulling open the door to the fridge and closing it again.

‘Where have you been? Are you OK?’

It had been two or three days since I had last seen her, only an unfinished cup of coffee on the counter when I woke that morning offering any sign that she had been home at all.

She looked odd, changed somehow, in a way that I could no longer ignore: her fingers scratching at her thighs, front teeth chewing her bottom lip. There was a darkness that had taken hold, its shadow stretching beneath her; an anger, barely contained, slowly tightening its grip.

‘Why?’

‘You just seem a bit … I tried to call.’

‘I’m fine, I’m tired. Work’s full on …’ Her eyes skittered around the room as if in search of an answer.

‘David rang, a minute ago, wanted to know if we were going to his party.’

Even as I said it, I knew I was setting myself up for a fall. Harry was away on a job, and although house parties were not my scene, especially not without Meg there to create a distraction, something had made me say yes.

‘Can’t, there’s something I’ve got to do.’ Meg’s voice was distant.

‘What is it?’

It stung that I even had to ask.

‘Just something for work.’

She walked out of the kitchen, and even though her bedroom stood directly on the other side of the wall, she could have been on the other side of the world.

When she came back out, half an hour later, her expression had softened slightly.

‘Sorry, I’m not myself at the moment, it’s just a lot of pressure.’

She held my gaze for a second before snapping her face away again. Without looking me in the eye, she stepped forward and kissed my cheek. There was a flicker of electricity between us and then she turned, the door slamming shut before I had time to reply.

The bus stop stood opposite our flat on the high street, illuminated in a sickly streetlight. Fifteen minutes later I stepped off the bus at South End Green, where the road veered right towards Hampstead Heath station.

Keeping the pub on my left I followed the right fork which led up to the Heath.

In all the years David and I had known each other, I had never been to his London house. After leaving halls, he had his own apartment in Brighton, on one of the smarter Regency squares, a very different proposition to the house we had shared the year previously.

The flat had been bought for him by his father, he let slip one afternoon. We were lazing on the nobbled rectangle of grass that stood between a U of buildings, sharing a bag of chips from soggy newspaper, the sea lapping at the shore on the other side of the main road. Back then, David still told himself he was uncomfortable with the level of wealth his father had started to accrue as his business grew from small-time independent to leading international trading company TradeSmart. The irony of his faux-liberal university lifestyle, banging on about the importance of fair trade while snorting lines of cocaine from supply chains involving child exploitation and murder, paid for by Daddy’s money, was not so much lost on him as ignored.