По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

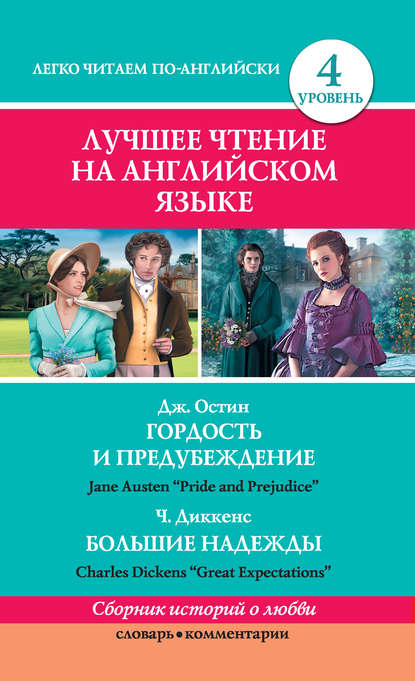

Гордость и предубеждение / Pride and Prejudice. Great Expectations / Большие надежды

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“And don’t you think he knows that?” asked Biddy.

It was such a very provoking question, that I said, snappishly —

“Biddy, what do you mean?”

“Have you never considered that he may be proud?”

“Proud?” I repeated, with disdainful emphasis.

“O! there are many kinds of pride,” said Biddy, looking full at me and shaking her head; “pride is not all of one kind[87 - pride is not all of one kind – гордость не у всех одинаковая] – ”

“Well? What are you stopping for?” said I.

“He may be too proud,” resumed Biddy, “to let any one take him out of a place that he fills well and with respect. To tell you the truth, I think he is.”

“Now, Biddy,” said I, “I did not expect to see this in you. You are envious, Biddy, and grudging. You are dissatisfied on account of my rise in fortune.”

“If you have the heart to think so,” returned Biddy, “say so. Say so over and over again, if you have the heart to think so.”

But, morning once more brightened my view, and I extended my clemency to Biddy, and we dropped the subject. Putting on the best clothes I had, I went into town as early as I could hope to find the shops open, and presented myself before Mr. Trabb,[88 - Trabb – Трэбб] the tailor.

“Well!” said Mr. Trabb. “How are you, and what can I do for you?”

“Mr. Trabb,” said I, “it looks like boasting; but I have come into a handsome property. I am going up to my guardian in London, and I want a fashionable suit of clothes.”

“My dear sir,” said Mr. Trabb, “may I congratulate you? Would you do me the favour of stepping into the shop?”

I selected the materials for a suit, with the assistance of Mr. Trabb. Mr. Trabb measured and calculated me in the parlor.

After this memorable event, I went to the hatter’s, and the shoemaker’s, and the hosier’s. I also went to the coach-office[89 - coach-office – контора дилижансов] and took my place for seven o’clock on Saturday morning.

So, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, passed; and on Friday morning I went to pay my visit to Miss Havisham.

I went to Miss Havisham’s by all the back ways, and rang at the bell. Sarah Pocket came to the gate, and positively reeled back when she saw me so changed.

“You?” said she. “You? Good gracious! What do you want?”

“I am going to London, Miss Pocket,” said I, “and want to say goodbye to Miss Havisham.”

Miss Havisham was taking exercise in the room with the long spread table, leaning on her crutch stick. She stopped and turned.

“Don’t go, Sarah,” she said. “Well, Pip?”

“I start for London, Miss Havisham, tomorrow,” I was exceedingly careful what I said, “and I thought you would kindly not mind[90 - you would kindly not mind – вы не сочтёте за дерзость] my taking leave of you. I have come into such good fortune since I saw you last, Miss Havisham, and I am so grateful for it, Miss Havisham!”

“Ay, ay!” said she, looking at envious Sarah, with delight. “I have seen Mr. Jaggers. I have heard about it, Pip. So you go tomorrow?”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“And you are adopted by a rich person?”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“Not named?”

“No, Miss Havisham.”

“And Mr. Jaggers is made your guardian?”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“Well!” she went on; “you have a promising career before you. Be good – deserve it – and abide by Mr. Jaggers’s instructions.”

She looked at me, and looked at Sarah. “Goodbye, Pip! – you will always keep the name of Pip, you know.”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“Goodbye, Pip!”

She stretched out her hand, and I went down on my knee and put it to my lips. Sarah Pocket conducted me down. I said “Goodbye, Miss Pocket;” but she merely stared, and did not seem collected enough to know that I had spoken.

The world lay spread before me.

This is the end of the first stage of Pip’s expectations.[91 - the first stage of expectations – первая пора надежд]

Chapter 20

The journey from our town to London was a journey of about five hours.

Mr. Jaggers had sent me his address; it was, Little Britain,[92 - Little Britain – Литл-Бритен] and he had written after it on his card, “just out of Smithfield.[93 - just out of Smithfield – не доезжая Смитфилда] We stopped in a gloomy street, at certain offices with an open door, where was painted MR. JAGGERS.

“How much?” I asked the coachman.

The coachman answered, “A shilling – unless you wish to make it more.”

I naturally said I had no wish to make it more.

“Then it must be a shilling,” observed the coachman. I went into the front office with my little bag in my hand and asked, Was Mr. Jaggers at home?

“He is not,” returned the clerk. “He is in Court at present. Am I addressing Mr. Pip?”

I signified that he was addressing Mr. Pip.

“Mr. Jaggers left word, would you wait in his room.”

Mr. Jaggers’s room was lighted by a skylight only, and was a most dismal place. There were not so many papers about, as I should have expected to see; and there were some odd objects about, that I should not have expected to see – such as an old rusty pistol, a sword, several strange-looking boxes and packages.

I sat down in the chair placed over against Mr. Jaggers’s chair, and became fascinated by the dismal atmosphere of the place. But I sat wondering and waiting in Mr. Jaggers’s close room, and got up and went out.

It was such a very provoking question, that I said, snappishly —

“Biddy, what do you mean?”

“Have you never considered that he may be proud?”

“Proud?” I repeated, with disdainful emphasis.

“O! there are many kinds of pride,” said Biddy, looking full at me and shaking her head; “pride is not all of one kind[87 - pride is not all of one kind – гордость не у всех одинаковая] – ”

“Well? What are you stopping for?” said I.

“He may be too proud,” resumed Biddy, “to let any one take him out of a place that he fills well and with respect. To tell you the truth, I think he is.”

“Now, Biddy,” said I, “I did not expect to see this in you. You are envious, Biddy, and grudging. You are dissatisfied on account of my rise in fortune.”

“If you have the heart to think so,” returned Biddy, “say so. Say so over and over again, if you have the heart to think so.”

But, morning once more brightened my view, and I extended my clemency to Biddy, and we dropped the subject. Putting on the best clothes I had, I went into town as early as I could hope to find the shops open, and presented myself before Mr. Trabb,[88 - Trabb – Трэбб] the tailor.

“Well!” said Mr. Trabb. “How are you, and what can I do for you?”

“Mr. Trabb,” said I, “it looks like boasting; but I have come into a handsome property. I am going up to my guardian in London, and I want a fashionable suit of clothes.”

“My dear sir,” said Mr. Trabb, “may I congratulate you? Would you do me the favour of stepping into the shop?”

I selected the materials for a suit, with the assistance of Mr. Trabb. Mr. Trabb measured and calculated me in the parlor.

After this memorable event, I went to the hatter’s, and the shoemaker’s, and the hosier’s. I also went to the coach-office[89 - coach-office – контора дилижансов] and took my place for seven o’clock on Saturday morning.

So, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, passed; and on Friday morning I went to pay my visit to Miss Havisham.

I went to Miss Havisham’s by all the back ways, and rang at the bell. Sarah Pocket came to the gate, and positively reeled back when she saw me so changed.

“You?” said she. “You? Good gracious! What do you want?”

“I am going to London, Miss Pocket,” said I, “and want to say goodbye to Miss Havisham.”

Miss Havisham was taking exercise in the room with the long spread table, leaning on her crutch stick. She stopped and turned.

“Don’t go, Sarah,” she said. “Well, Pip?”

“I start for London, Miss Havisham, tomorrow,” I was exceedingly careful what I said, “and I thought you would kindly not mind[90 - you would kindly not mind – вы не сочтёте за дерзость] my taking leave of you. I have come into such good fortune since I saw you last, Miss Havisham, and I am so grateful for it, Miss Havisham!”

“Ay, ay!” said she, looking at envious Sarah, with delight. “I have seen Mr. Jaggers. I have heard about it, Pip. So you go tomorrow?”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“And you are adopted by a rich person?”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“Not named?”

“No, Miss Havisham.”

“And Mr. Jaggers is made your guardian?”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“Well!” she went on; “you have a promising career before you. Be good – deserve it – and abide by Mr. Jaggers’s instructions.”

She looked at me, and looked at Sarah. “Goodbye, Pip! – you will always keep the name of Pip, you know.”

“Yes, Miss Havisham.”

“Goodbye, Pip!”

She stretched out her hand, and I went down on my knee and put it to my lips. Sarah Pocket conducted me down. I said “Goodbye, Miss Pocket;” but she merely stared, and did not seem collected enough to know that I had spoken.

The world lay spread before me.

This is the end of the first stage of Pip’s expectations.[91 - the first stage of expectations – первая пора надежд]

Chapter 20

The journey from our town to London was a journey of about five hours.

Mr. Jaggers had sent me his address; it was, Little Britain,[92 - Little Britain – Литл-Бритен] and he had written after it on his card, “just out of Smithfield.[93 - just out of Smithfield – не доезжая Смитфилда] We stopped in a gloomy street, at certain offices with an open door, where was painted MR. JAGGERS.

“How much?” I asked the coachman.

The coachman answered, “A shilling – unless you wish to make it more.”

I naturally said I had no wish to make it more.

“Then it must be a shilling,” observed the coachman. I went into the front office with my little bag in my hand and asked, Was Mr. Jaggers at home?

“He is not,” returned the clerk. “He is in Court at present. Am I addressing Mr. Pip?”

I signified that he was addressing Mr. Pip.

“Mr. Jaggers left word, would you wait in his room.”

Mr. Jaggers’s room was lighted by a skylight only, and was a most dismal place. There were not so many papers about, as I should have expected to see; and there were some odd objects about, that I should not have expected to see – such as an old rusty pistol, a sword, several strange-looking boxes and packages.

I sat down in the chair placed over against Mr. Jaggers’s chair, and became fascinated by the dismal atmosphere of the place. But I sat wondering and waiting in Mr. Jaggers’s close room, and got up and went out.