По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

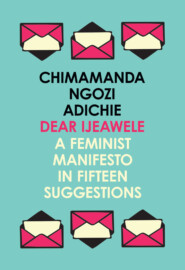

Half of a Yellow Sun, Americanah, Purple Hibiscus: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Three-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Olanna jumped each time she heard the thunder. She imagined another air raid, bombs rolling out of a plane and exploding in the compound before she and Odenigbo and Baby and Ugwu could reach the bunker down the street. Sometimes she imagined the bunker itself collapsing, squashing them all into mud. Odenigbo and some of the neighbourhood men had built it in a week; after they dug the pit, as wide as a hall, and after they roofed it with clay-layered palm trunks, he told her, ‘We’re safe now, nkem. We’re safe.’ But the first time he showed her how to climb down the jagged steps, Olanna saw a snake coiled in a corner. Its black skin glistened with silver markings and tiny crickets hopped about and, in the silence of the damp underground that made her think of a grave, she screamed.

Odenigbo bashed the snake with a stick and told her he would make sure the zinc sheet at the entrance of the bunker was more secure. His calmness bewildered her. The tranquil tone he used to confront their new world, their changed circumstances, bewildered her. When the Nigerians changed their currency and Radio Biafra hurriedly announced a new currency too, Olanna stood in the bank queue for four hours, dodging flogging men and pushing women, until she exchanged their Nigerian money for the prettier Biafran pounds. Later, during breakfast, she held up the medium-sized envelope of notes and said, ‘All the cash we have.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: