По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

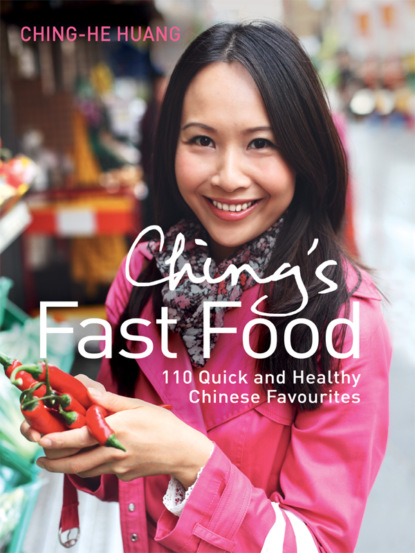

Ching’s Fast Food: 110 Quick and Healthy Chinese Favourites

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

2 tbsps of cornflour mixed with 4 tbsps of water

1 large spring onion, finely sliced

180g (6½oz) cooked crayfish tails in brine, drained

1. Pour 1 litre (134 pints) of water into a large wok or saucepan and bring to the boil. Add the crabmeat, sweetcorn and tomato and bring back up to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 5 minutes.

2. Add the beaten eggs and stir gently to create a web-like pattern in the soup as the eggs start to cook. Season with the soy sauce, sesame oil and salt and pepper, adding more to taste if necessary. Bring to the boil and then stir in the cornflour paste to thicken the soup. Reduce the heat, sprinkle in the spring onion and leave to simmer on a gentle heat until ready to serve.

3. Ladle the soup into serving bowls, top with a few crayfish tails (which will warm through in the heat of the soup) and serve immediately.

ALSO TRY

You could substitute the crabmeat with cooked sliced chicken breast or, for a vegetarian option, use diced marinated dofu or sliced shiitake mushrooms (or chestnut mushrooms if you are on a budget). If you want a creamier consistency, use tins of creamed sweetcorn instead.

Mum’s herbal eel soup

I wanted to include this more unusual recipe even though it doesn’t really have a connection to Chinese takeaways in the West. In Hong Kong, on the other hand, there are eateries that serve herbal soups such as this to take away. Don’t be put off by the sound of this soup – it’s actually quite delicious, although admittedly an acquired taste. You will either love or hate it – for me, it’s love. It’s also very good for you. If you can, add a few dried goji berries to the soup 15 minutes before the cooking time is up; it lends a mellow sweetness to the broth. These, together with the other herbs, can be bought from a Chinese supermarket.

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 65 minutes

SERVES: 4

600g (1lb 5oz) fresh river eel, head and tail discarded and any fins removed (or ask your fishmonger to do this for you)

2 tbsps of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

½ tsp of salt

1 tbsp of vegetable bouillon powder or stock powder

5g (¼oz) Angelica sinensis (Chinese angelica or dong quai)

5g (¼oz) rhizome of rehmannia

8g (

/

oz) Ligusticum wallichii (Sichuan lovage)

5g (¼oz) matrimony vine

5 dried red dates

2 x 5cm (2in) sticks of cassia

1 x 5cm (2in) stick of cinnamon

Small handful of dried goji berries (optional)

1. Slice the eel into 5cm (2in) pieces, keeping the bones intact, then rinse well. Place the pieces in a large saucepan of boiling water to blanch for 2 minutes and then drain and set aside.

2. Place the blanched eels back in the pan. Pour in 1.5 litres (2½ pints) of water and add all the remaining ingredients except the goji berries. Bring to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 1 hour or until the eel is tender and delicious. If using the goji berries, add these for the final 15 minutes of cooking.

ALSO TRY

If you’re not so keen on the idea of cooking eel, then simply substitute it with chicken or pork ribs.

Appetisers

‘No, Peking duck is better.’ This is what my father would insist whenever he saw crispy aromatic duck on the menu at a Chinese restaurant. On one occasion I felt I had to intervene; I could see the disappointed look on the Swiss husband of one of my father’s guests. I told my father I had a craving for crispy duck and he called me a wai guo ren (foreigner) in front of his friends, at which everyone laughed, the Swiss man included. I couldn’t believe it! For the first time, I had put myself in the firing line to satisfy someone else’s craving for a particular dish. On the plus side, I now occupied the moral high ground. I had been selfless in the sacrifice of my dignity for the happiness of another and thought my Buddhist master would be proud of my spiritual development (even if I was still a self-confessed carnivore).

Since my ‘enlightening’ crispy duck experience, I was actually enlightened once again, years later, to find that crispy aromatic duck is basically Chinese in origin and not something just concocted for foreigners, bearing a resemblance to tea-smoked Sichuan duck, Cantonese roast duck and Peking duck. All four dishes use Chinese five spice, the difference being that crispy aromatic duck is deep-fried rather than oven-roasted. When I told my father this, he still maintained in his father-knows-best tone that ‘crispy duck is no good anyway because they fry the duck on its last days of freshness’.

Crispy aromatic duck seems to be confined to the UK. The debate continues about who invented it. According to the previous generation of Chinese food lovers, the Richmond Rendezvous Group – a chain of restaurants that created the boom in Chinese cuisine in the mid-1960s – was responsible for this delicious recipe that is consistently voted as the No. 1 Chinese takeaway dish in Britain.

Peking duck is equally popular: Beijingers see it as the national dish of China, the crème de la crème of all dishes. Chefs are super-proud of the delicious smoky golden skin of the duck and tender, succulent flesh, achieved by first slathering the bird in a maltose glaze and airdrying for eight hours before filling with water and cooking it in a wood-fired oven so that the meat is steamed on the inside while the outside remains crisp. At a good restaurant, the waiter will meticulously carve the skin and meat in front of you and serve the skin with some fine sugar. This will be served with thin steamed pancakes made from wheat flour, sliced cucumber, spring onions and a good tian mian jiang (sweet flour sauce). You should also expect a good restaurant to ask you how you would like the rest of the duck cooked – either in a delicious herbal broth soup or in a stir-fry with lush greens (I usually go with the chef’s recommendation). Both Peking duck and crispy duck are on my top list of favourite starters, so they are both included in this chapter, although my version of Peking duck is more like Cantonese roast duck because it is easier to recreate in the home kitchen.

I now have a tendency to judge dinner hosts based on their diplomacy when it comes to ordering (even if they are paying) and I am careful to be as sensitive as possible, to the point where I might be accused of being too nice. But better to be that, in my opinion, than greedy and selfish with no manners. There is a real art to ordering and being a good host; it takes real skill or gong-fu (kung fu). The Chinese are known for their generosity when it comes to dining, but a fine line needs to be trodden there as well: order too much and you look like a show-off; too little and you are seen as a scrooge. I take advice from my Buddhist master and that is: always finish what is on the table. It is better not to waste good food – think of all the people who go hungry.

When it comes to dinner parties at your own home, one thing is for sure: the very first dishes should impress. First impressions count. Like a teaser trailer to a blockbuster film, it should give you a hint of what to expect but without giving the whole plot away. It should excite and thrill you, satisfying you up to a point while leaving you hungry for more.

I usually serve a combination of ‘yang’ dishes, ‘yang’ being my label for ‘fried’ because it doesn’t sound so bad. Yes, we all know that fried food comes with an ‘unhealthy’ tag, but it is all a matter of what you choose to eat. If you served and ate only fried food, you would soon be in A&E. Like everything in life, food choices are about balance. ‘Yang’ is appropriate because, in food terms, it means ‘hot’ energy, i.e. food that creates more ‘heat’ within the body. The opposite of this is ‘yin’ or cooling energy. It is not good for the body to be too ‘yang’, as it puts stress on the body. So my ‘yang’ menu carries this health warning – do not serve all these fried dishes in one meal; they are meant to be served only as an accompaniment to a variety of balanced dishes.

I have included many of my favourite naughty ‘yang’ takeaway starters (see Appetisers) such as Pork and Prawn Fried Wantons and Crispy Sweet Chilli Beef Pancakes, my take on crispy duck pancakes. If this is all too ‘yang’ for you, then fear not, as I have also included some ‘leng’ starters, i.e. ‘cooling’ dishes that are more balanced and not fried (see Appetisers).

Vegetable spring rolls (chun juen)

Some may think this isn’t a traditional Chinese dish – but it is, usually eaten at the Spring Festival or Chinese New Year. It has northern Chinese roots where wheat flour is the main form of carbohydrate and bings – semi-rolled pancakes – are eaten, with various delicious fillings wrapped inside.

PREP TIME: 20 minutes, plus 10 minutes for cooling COOK IN: 7 minutes

MAKES: 12 small rolls

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

1 tsp of peeled and grated root ginger

100g (3½oz) shiitake mushrooms, sliced

100g (3½oz) tinned bamboo shoots, drained and cut into matchsticks

1½ tbsps of light soy sauce

1 tbsp of Chinese five-spice powder