По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

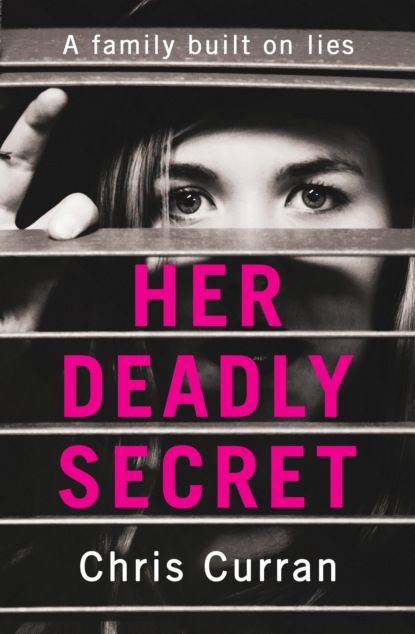

Her Deadly Secret: A gripping psychological thriller with twists that will take your breath away

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Chris Curran (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#ud6f98b2e-a18d-5fd9-bd14-a63d151d83b8)

This one is for Sue Curran and Jack Farmer, with love.

What would I do without you?

Chapter One (#ud6f98b2e-a18d-5fd9-bd14-a63d151d83b8)

Joe

As the police car brought him home, Joe saw a crowd outside and the cameras started up again. He still had black spots in front of his eyes from the last lot.

It was nearly midsummer, so still daylight at seven in the evening, and coming through the estate he’d noticed how run-down the area looked and realized their own house must seem no better. He had been doing it up, hoping to sell and move somewhere nicer, but he’d been away a lot recently. So the paintwork was peeling on the old front door and the bricks he’d bought to rebuild a wall were piled under the window. Lit up by those harsh flashes, with the knot of people crowding round the gate, it looked not half-finished but neglected.

The kind of place where bad things happen.

He’d used the word exhausted before, coming home from a surveying job at the other end of the country, but this was different. His whole body ached with it. He’d spent two nights driving around Swindon and, when it became light, walking the streets. He’d scoured the parks, getting funny looks from joggers and women with pushchairs, aware he must look half-mad.

The way Hannah was going on didn’t help. She stayed in her dressing gown the whole time, lying on the bed, or sitting at the kitchen table. When he tried to hold her she kept herself stiff, arms by her sides. He talked and talked, telling her where he’d been and what he planned to do next. Instead of speaking she pushed plates of toast or sandwiches in front of him and left him to it. When he did crawl into bed with her for a few minutes she turned away or got up and went downstairs.

At first, the police didn’t seem to take Lily’s disappearance seriously. Hannah had rung him about half past six that night in a panic. Lily was never late back from school and none of her friends had seen her. He’d driven fast, and as soon as he’d got in, dialled 999, and a patrol car came round. But the two uniforms seemed to think it was normal for a 14-year-old to stay out late without letting anyone know. Said they’d ‘look into it’, whatever that meant.

On the third day, they came back; three of them this time. He recognized the black woman constable from that first night, even though she was no longer in uniform. The one in charge introduced himself as Detective Chief Inspector Philips, and explained that Loretta was now their Family Liaison Officer. The woman nodded at Joe, her expression telling him she wouldn’t trust him as far as she could throw him, and went upstairs to see Hannah.

Philips said they now had to treat ‘the disappearance’ very seriously. ‘The likelihood is that she’s gone off somewhere. Maybe something’s upset her or she thinks she’s in trouble, but we need to find her as soon as possible.’

They asked him lots of questions about Lily. How did she get on at school; did she have a boyfriend? He answered as best he could, but too often found himself saying stupid things like, ‘You’d better ask her mum about that.’ All he wanted was to get out again. To do something. Anything but sit here with them watching him. He knew he was fidgeting as he tried to hear the voices upstairs, anxious in case Hannah’s answers were different from his, but he couldn’t help it.

Philips suggested a TV appeal. ‘If there’s still no sign of her by then. I’ll be with you and I can help you with what to say.’

Of course he agreed, and they said Hannah should be there too. She wouldn’t have to speak if she was too upset. But when the policewoman came down she gave the inspector a look and said Hannah wouldn’t do it; nothing could persuade her.

He’d hated doing the appeal and now, as they got out of the car, Philips told him to ignore the reporters. It wasn’t easy with all the cameras and with microphones shoved in his face, one of them knocking against his mouth. Philips stood close to him, and the smell of his sickly aftershave, which had bothered Joe all evening, was very strong. He turned away, preferring the whiff of BO and damp cloth coming from the crowd.

‘Clear the way now. Let us through. Mr Marsden has nothing more to say.’ Philips pushed them both forward, and Joe took the chance to stab his elbow into the guy with the microphone.

The Family Liaison Officer, the one they were apparently meant to call Loretta, was with Hannah at the kitchen table. Hannah didn’t even look up let alone ask how it had gone. Why was she leaving it all to him? Couldn’t she see he needed her?

Philips said, ‘Excuse me, Joe,’ and fumbled in his pocket as his phone chirruped. He kept calling Joe by his first name, even though he hadn’t asked if that was OK and hadn’t offered his own. He turned away muttering into the phone, and Hannah was suddenly standing, brushing off Loretta’s hand and walking towards Joe.

He felt the tears he’d been holding back for so long shift, a lump of rock in his throat, and he moved forward wanting only to cry at last in the warmth of her arms.

But she was looking past him. And her face was terrible. And Joe saw Philips. Saw the tight line of his mouth, the slight shake of his head as he looked over Hannah’s head at the policewoman.

The world stopped. Something hammered in his ears. There was an agony in his throat, and the kitchen had turned into a shimmering photograph; a place he didn’t know.

And in front of him – Hannah. Pale mouth stretched wide with no sound. Hands in her hair, as if she wanted to tear it out by the roots.

He made himself move. Reach for her as she began a broken chant, ‘No, oh no, no, no.’ He pulled her into his arms. She clung to him, and he closed his eyes pressing his face into her hair. Her heart thumped hard against his chest, echoing the rhythm of his own. If they could stay like this, just the two of them, they could hold back the nightmare.

But then she pushed him away and, as he tried to touch her again, she beat at him, hitting his chest, his face, his eyes, her hands clenched into stones. He tried to speak but, as Philips dragged him back, Hannah shrieked so loudly Joe was sure the whole world could hear.

‘Don’t touch me, Joe. Don’t touch me. Keep away from me.’

Rosie

It didn’t help that it was Alice’s birthday today – what would have been Alice’s birthday. At ten o’clock Rosie switched to another news channel just in time to see the photo of the missing girl again. A slim face and light brown hair, held up at one side with a blue clip. She had already watched the whole of today’s appeal three times. And now there was a sentence of breaking news rolling along the bottom of the screen.

Body found in search for missing teenager.

The girl’s family must have heard already, and she could imagine all too easily what it would be like in that house now.

She wrapped the soft throw more tightly around her legs on the big sofa, curling her bare feet under her. It crossed her mind to put the central heating on or move to the kitchen. The sitting room, which had seemed so elegant when they bought the place, always felt cavernous when Oliver wasn’t at home; the windows too large even with the curtains closed. She wished they hadn’t positioned the sofa in the middle of the room near the fireplace and TV, where you had to look behind you to see the door and the hallway.

The kitchen was large too, and they’d extended it to make a dining area which was nearly all glass. She shivered at the thought of pulling the blinds in there, one by one, while the lights turned the garden into a black emptiness. She always had the feeling that someone was out there, staring in at her.

Here was the news conference again, coming from Swindon. She’d never been there, but thought it was in Wiltshire, about a hundred and fifty miles away from their home in Hastings. The policeman in charge was explaining they were seriously concerned about Lily, because she was only 14 and she wasn’t the kind of girl to go off without letting her parents know. Unusually, the mother was absent and the dad looked very lonely up there, flanked by the row of uniforms, a bank of microphones in front of his face.

He was coughing now, the father, as the police inspector said Mr Marsden had a message for his daughter and cameras clacked like a volley of gunshots in the man’s face.

‘Lily, love, if you can hear this we’re worried about you … sweetheart. So come home if you can. We won’t be cross with you if you’re in … I mean, if you’ve done something wrong.’ He stumbled to a halt, cleared his throat and glanced at the policeman, whose nod told him to go on. ‘Your mum’s beside herself with worry.’ He gulped at a glass of water. ‘We both are; so, please call us if you can. Just to say you’re all right.’

The father stopped, looked up then flinched back into himself as the cameras flashed. He turned to the policeman. ‘That’s all.’ Looking down, his face red and voice gruff, suggesting tears held back, he muttered to the table, ‘We love you, Lily.’

As the cameras clattered and flared at him again, Rosie wondered whether he knew that, if the body they’d found was his daughter’s, he would soon be the prime suspect.

‘Mummy, Muuum.’

The cries must have been going on for some time, and she bounded across the hallway, the parquet floor cool under her feet.

Fay’s room was warm, but she was sitting up in bed, eyes puffy with sleep and tears. ‘I had a dream and you didn’t come.’

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t hear you.’ Rosie sat on the bed, holding her daughter and kissing her hair. It smelled musty with sleep.