По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

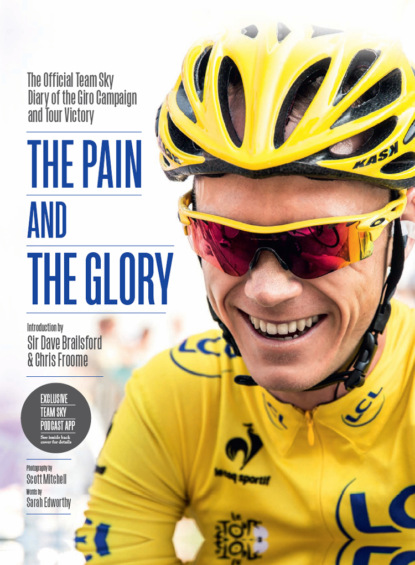

The Pain and the Glory: The Official Team Sky Diary of the Giro Campaign and Tour Victory

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The effort to get Urán back in the pack was exhausting, but Cataldo, Puccio and Zandio managed it 100m before that last ascent. Afterwards, Ljungqvist was quick to praise Cataldo’s stalwart efforts. ‘He’s done well to battle through his illness and hopefully now he’s coming out the other side.’

According to the team doctor, Richard Freeman, Cataldo picked up an infection early in the race. ‘It’s not unusual. When they’re training hard the immune system is diminished. The first week is actually the time riders are most likely to get sick. Training culminates, and tapers. Travel to the Grand Tours has its risks. They’re mixing with the general public, meeting people from all over the world. Dario was gutted. After months of training, it’s bad enough to fall off your bike – but to go down with a common-orgarden infection is frustrating. Because of the nature of the Giro, it was hard to get on top of his bug. Every day he was exhausting himself, four, five, six hours in the saddle. He was isolated and given his own room. The chef made special food, which I took up to him on a tray. He liked it so much that at 2.30am he called me, wanting more!’

Rain, punctures, crashes, illness . . . The sunny times on Ischia seemed a world away. ‘For sure, it happens every Grand Tour,’ said Dan Hunt, cheerfully. ‘There isn’t a team that doesn’t go through adversity. It’s a “here we go” sort of thing. That’s the kind of sport it is. Illness takes the edge off you, but you tend to get through it in a couple of days. We do express sympathy, but the guys are pretty brutal with each other. There’s a lot of banter and taking the piss.’

Skip photographs (#u35562de9-ff35-52c6-80e5-bfcb6b7692bf)

STAGE 6 (#ulink_f1ef03ae-39a9-53fb-b89a-19c2e7fcae8c)

‘Our goal will be to keep Bradley, Rigo and Sergio out of trouble and allow the other guys, like Dario, to rest up as much as possible before the tough test tomorrow.’ So declared Marcus Ljungqvist on the morning of a day on which the sprinters’ teams were expected to control things from start to finish. It was a sound idea but, as usual, Lady Luck had other plans. The route hugged the picturesque Adriatic coastline before arriving in Margherita di Savoia, where two laps of the 16.6km Circuito Delle Saline saw the sprinters move into their most maniacal form of queue-barging just as space became tight, making crashes inevitable.

Wiggins, who famously hates the first week of a Grand Tour, had yet another early scare on a fourth consecutive nerve-shredding day. First, he suffered a mechanical problem that forced a bike change. Just as he was settling back at pace, in position on the first of the two laps of the finishing circuit, he found himself barricaded behind a crash and an extensive tangle of bikes, spinning wheels and ripped Lycra. Aided by his team-mates, he managed to hitch back on to the leading group – which had slowed by convention, albeit somewhat reluctantly – and remarkably ended up leading the pack with 3km remaining.

It was an admirable show of resilience, but for road captain Knees it was an equally fretful experience. ‘Bradley needed a bike change minutes before that crash, so although he wasn’t involved in it, he did get stuck behind it,’ the German confirmed. ‘The boys did a brilliant job pacing him back on, but I got caught up the road. It was so loud in the bunch that I couldn’t hear over the race radio what had happened behind me until it was too late. When I found out, I went straight to the front and told the FDJ and Quick Step guys to stop pulling. They agreed to ease off a little, but the pace was still high, so the boys had to ride hard to bring Bradley back on. They did a great job, and I then moved him towards the front to keep him out of any further trouble. This was the last sprint day for a while, so that’s why it was so hectic. We knew we had to stay safe at the front. In the end we did that, so we’re all happy with how things turned out.’

Wiggins was relieved to tick off another stage with his overall title hopes intact. He was one of the first to congratulate former Sky team-mate Mark Cavendish, who – at last – had enjoyed a textbook lead-out from his new team, Omega Pharma-Quick Step. Cav went on to dedicate his win to the memory of Belgian rider Wouter Weylandt, who had crashed and died exactly two years ago to the day.

Ljungqvist was left relieved, if a tad rueful, about the difference a few hours can make to his day-by-day Giro overview. ‘That was a fantastic team performance today and everything worked out in the end. As soon as Bradley needed a new bike, there were seven riders around him and Christian was able to slow things down up the road. It took some hard work to bring Bradley back on, but these guys will recover tonight ahead of a tough day tomorrow.’

Skip photographs (#ua53c2a48-f5cb-53be-acac-558b4544928e)

STAGE 7 (#ulink_3b9ea7d8-1187-5bfe-a4ca-8a404b140ec6)

There is no such sentiment as ‘Thank God it’s Friday’ in the professional cyclist’s week. Nothing about the profile (a continuously testing route, marked by four tricky categorised climbs and an irritating series of small, steep ramps) or the conditions (heavy downpours and greasy roads) suggested that Friday 10 May would include a happy hour. The forecast had always been ‘tough’; the reality for Team Sky was worse. Every day, Brailsford had gee’ed up Wiggins by exhorting him to count down the days until Saturday’s individual time trial. ‘Get through today with concentration,’ he’d say from the rear of the team bus during the directeurs sportifs’ presentation of the day’s stage profile. ‘It’s another day gone, another box ticked.’ On paper, this was the last of those days that had to be survived.

The Giro seemed now to be travelling in its own microclimate of glowering skies and perpetual rain. However long the transfer between stages, whatever the bearing – eastwards, northwards, north-westwards – the team always stepped off the bus to find the weather had not brightened. ‘When it’s raining, I don’t love it,’ said Wiggins glumly. On that Friday ride into Pescara, the conditions were testing and the pace fast. The peloton went through its usual dynamic at accelerated speed – the riders settling into the stage, marshalling potential breakaways and eventually releasing a small group that wouldn’t threaten anyone’s specific ambitions – and then started to splinter dramatically under the lashing rain and the demands of the sharply undulating route.

‘It was a complicated day. The weather was very cold, the conditions were very difficult, we were going full-gas from the start,’ said Urán. ‘It was a fast day, uphill, very hard, attacking on climb after climb because of the pressure other teams were putting on Bradley. Both Sergio and I were working hard for Bradley to bring him back on to the lead group after each attack. We were leading him out. I was calm. I had no worries. And then Bradley fell.’

Wiggins was one of many, including race leader Paolini, who slid and fell as they powered downhill at high speed. His tumble came as he attempted to round one of the mountain hairpins on the final descent. ‘Sergio and I were waiting around the next corner for him, but he didn’t come,’ Urán continues. ‘Usually he gets straight back up, but when he didn’t appear we started to wonder if he’d broken his collarbone. Eventually he came back, but his head was not fully there. It was pissing down. It was cold. He was knackered. We tried to guide him back to the front to make up the time, but he’d lost his concentration.’

The Team Sky leader rode gingerly to the line – right elbow and knee bloodied, his ripped Lycra also revealing a grazed hip – to discover he had dropped from sixth place to 23rd, and had lost 1 minute and 24 seconds to all his major rivals.

‘It’s all about how much balls Brad has now,’ was how Brailsford put in to the media, as he consigned the day to the ticked-off list and pointed to the recovery potential offered by the next day’s individual time trial. Once earmarked as the stage on which Wiggins could unleash his natural prowess against the clock and launch himself into the high mountains with a comfortable lead over his rivals, the ‘Race of Truth’ was now another ultra-stressful day, a pivotal day of catch-up.

How serious were his injuries? Would they affect him going forward? ‘Bradley’s crash was not anything spectacular and would have had negligible effect on performance,’ said team doc Richard Freeman, who was following in the team car. ‘A graze is painful and uncomfortable. He lost skin on his hip, elbow and knee, but it wouldn’t have stopped him performing. Grazes are a normal issue. There was no deep tissue damage. It would have been worse if there had been a bleed into the muscle or a bruised bone. But if you’re already miserable, those kind of injuries make you even more miserable . . .’

Hmm. For the first time, observers started to wonder if there was something else gnawing at Wiggins beyond the first-week trials and tribulations. Vincenzo Nibali had also had a fall on the same descent, but had bounced back up and pressed on like a man possessed, to rejoin the group that vainly chased the day’s breakaway winner, Adam Hansen. Wiggins seemed a tiny percentage off his characteristic form. How much was he out of sorts?

‘Not much seemed out of the ordinary to us,’ said Danny Pate. ‘Those days are still kind of normal for the Giro. But Brad really compartmentalises his own emotions. He may have seen the storm coming. He was feeling bad in his own health and he was really not enjoying those bad-weather days. But he was getting through them. One thing a team leader doesn’t do is be super-negative and drag down the team. Brad’s best quality is that he doesn’t do that. We never knew until much later that he was starting to feel ill.’

Urán and Henao also plummeted out of the top ten – Urán was down to 22nd, when he might have been in the maglia rosa had he not turned back for his leader. Typically, he was not bothered. ‘I do what the team asks me to do, whether I’m working for a team leader or I’m leading myself. It might have put me in a good position if I hadn’t had to stop, but my job is to wait for my team leader.’ But with that sense that the team leader was not descending well, the outside world questioned the team principal on the decision to send the Colombians back. ‘It’s the team’s call,’ said Brailsford. ‘Urán and Henao are here to ride for a leader. When you’re dedicated to a single leader, that’s the call that the team makes and that’s the right call as far as I’m concerned. You’ve got to take setbacks on the chin and you have to show character. That’s what it’s all about. You have to keep fighting right until the end and that’s what we’ll aim to do.

‘There’s a long way to go. Bradley’s fine. There’s no physical injury. Ultimately, when you have difficult conditions like these and hard racing, this type of thing can happen. It’s the Giro. You can have good days and bad days, and you have to wait until the end to tot them all up and see where you are. It’s a setback, but Brad’s still very much in the hunt. We’ve now got to take each day as it comes, focus on fully recovering tonight and hitting the time trial hard tomorrow. We’ll see where we are tomorrow night, and take stock of the situation then.’

Skip photographs (#u799ba038-c731-51d6-b323-13333f1ad110)

STAGE 8 (#ulink_3660a6f7-30d0-53f4-89c8-f4f60cabfc5e)

The pivotal day dawned. Could Wiggins do his stuff and claim the maglia rosa? Waiting for each rider, rolling down the start ramp at two-minute intervals, was a 54.8km course that challenged technical skill as much as stamina and judgement of pace. The fan-lined ramp up to the finish at Saltara was a sting in the tail, giving spectators a close-up view of the agony etched on each rider’s face as they eked out their last watt of power towards the line. As Wiggins noted, ‘It’s one of those tests where you have to be good from start to finish. If you die off at the end, you’re going to lose three minutes on the final climb.’

Team Sky approached the potential Sir Bradley Wiggins masterclass with customary forensic scrutiny. Wiggins had ridden the route, studied videos and absorbed the opinions of his support team. The plan was to get up early, ride the first 30km again, drive the final 25km, then get on the turbo bike, plug in the pump-up music and let the adrenalin take over.

Under cloudy skies and sporadic sunshine, Alex Dowsett – a former Team Sky rider and Giro débutant – set a time early on that was proving unmatchable for rider after ever more highly placed rider. As Wiggins sped off the starting gantry, alone in a private world of pain and focus, his junior compatriot’s time of 1 hour, 16 minutes and 27 seconds was still the time to beat. Wiggins was the Olympic road time trial champion, an undisputed expert at getting from A to B with superb aerodynamic efficiency, but it was nerve-wracking watching his progress over the tight, technical course. The winding narrow country lanes made it difficult to get into a rhythm. The previous day had not been an ideal lead-in, but surely here he could reverse the momentum of the last week for himself?

Eighteen minutes in – yet more wretched luck. Wiggins was indicating ‘puncture’ with a frantic gesture to the team car shadowing him. He was off his new Pinarello Bolide time trial bike, chucking it into the hedge, and back on his old Graal model, trying to stay in the zone, striving to re-establish his rhythm. It was another blow. The loss of precious seconds left him ‘a bit ruffled’. At the first intermediate split, he was 52 seconds down, only seventh fastest.

‘We did a swift bike swap but he lost advantage there and broke his rhythm,’ said Dan Hunt, who was in radio contact with him from the car behind. ‘I started to get this feeling . . . There are problems everywhere we turn.’

Digging in deep, Wiggins made up time in the latter part of the course and finished second, 10 seconds down on Dowsett. It was a result that left him not in the pink jersey – and not with a sizeable cushion of a lead to defend in the mountains – but in fourth place overall, 1 minute and 16 seconds down on Nibali, and behind Cadel Evans and the Dutchman Robert Gesink. ‘It’s all to play for, still,’ he said phlegmatically. ‘There was initial disappointment because I wanted to win the stage. But it is what it is. It’s going to be a hell of a race for the next two weeks.’

Skip photographs (#u002727c7-409e-5128-a0fe-db8bf5500194)

STAGE 9 (#ulink_b08a75e6-208c-5eb2-b4cb-b89e54c91d0d)

It was another thrilling day of unpredictable action and unsung heroes – and yet more skid-pan corners, as leaden skies dropped relentless waves of heavy rain. While Maxim Belkov of Russia broke clear of a breakaway on the penultimate climb, the Vallombrosa, soloing his way to a 44-second clear victory, the peloton was hyperactive with all sorts of attacks and probing moves. ‘It wasn’t super pleasant out there,’ said Danny Pate. ‘It was fast from the start. A couple of different groups formed and then finally we got the breakaway. It was quite big, and having one guy in there – Juan Manuel Garate, who was only 5 minutes down in the GC – the peloton never let it go out very far.

‘The two big climbs in the middle were hard, too. When it was time to bridge the gap we stayed together. Any time you have to do a chase, one of the key things is not to panic. We tried to bring our group back to the main group and we managed it right on the Category-3 climb. We had Rigo and Sergio ahead, and everyone else was behind helping Brad. After he got back on, that was it – I was pretty much blown!’

All eyes were on Wiggins, who had dropped back on the long series of bends off the same mountain Belkov used as his launch pad to victory. Although his team-mates escorted him at pace for 20km to regain contact with the maglia rosa group, questions were arising about whether the British knight had lost his ‘descending mojo’. The toil required to rejoin the group demanded an enormous effort from Wiggins, too. Although he had his Team Sky colleagues to help, he did much of the work himself, leaving himself empty as he struggled to hold on during the day’s final two climbs, shorter and punchier than those that had preceded them, and looked in peril again on the descent from Fiesole.

‘I was riding right behind him,’ said Giovanni Visconti. ‘I could see he was handling the descents very badly. I think when it comes to descents he’s now got some kind of mental block.’ You could dismiss that as a bit of psychological warfare from another team, but Christian Knees made a similar observation: ‘Bradley was a little bit nervous downhill. Bad luck with the weather meant the roads were very slippery. He still had confidence in his climbing skills and his ability. He kept fighting. He was the same Bradley, mentally thinking all the time about how to win, but he was a little bit cautious.’ Two days later, Wiggins, never one to make excuses, reflected on his performance and said: ‘Let’s be honest. I descended like a bit of a girl after the crash . . . Not to disrespect girls, I have one at home. But that’s life and we have to push on and deal with the disappointments.’

‘Everyone thinks uphill is the big challenge, but downhill can play a big part,’ said Pate. ‘Uphill, you need a good power-to-weight ratio. Downhill, you need to be a bit crazy. Some descents are over 100 km/h. They’re fun, exhilarating, scary, frightening . . . how you take them all depends on who you are. Some guys have way more confidence than skill and ability. Some guys are out of their minds. People think the sprinters are crazy. Some of the downhill guys are crazy, too. Personally, I’m okay downhill, but if I crash it definitely takes me back a notch. It takes me a while to regain confidence. You can get really shaken up – but some guys don’t get shaken up; a crash doesn’t affect them.

‘The Giro is an annual race, but every edition has different stages, routes, climbs and descents,’ he continues. ‘Some descents are fast, some are more technical, with tight turns. It’s a real mix, all on one road. I think the Giro is unique in that aspect. A lot of road we’re riding pretty blind. We have profiles, radio information, maps, but there’s always going to be stuff we haven’t raced down. It can be pretty tricky. To my mind, there’s risk and there’s reward, but some guys are definitely big risk-takers. Nibali is known for being good at going downhill, but I’ve seen him crash quite a bit. He crashed twice that same day Brad did, but he doesn’t get shaken up. A guy crashed at the same time, just behind Nibali, and he broke ribs, a scapula and collarbone. That could have been Nibali – out of the Giro, and all for an unnecessary downhill attack.’

Tellingly, Nibali told Italian TV station RAI afterwards that he had not been exploiting the difficulties Wiggins was encountering because he was unaware of them. His team car had been relegated to last position after a previous rule infraction. By the time BMC and Garmin-Sharp had moved to the front to try and force the pace, Wiggins and Team Sky were already bridging back across.

So, Wiggins remained in fourth going into the rest day. The day’s big loser was Ryder Hesjedal, who lost more than a minute to his rivals and slipped out of the top ten after being dropped on the final climb. ‘The stage worked out well in the end for us,’ said Ljungqvist. ‘The guys raced as a team, didn’t panic and that was the key. We were able to chase down the gap and we’ve moved up the GC with Rigoberto and Sergio. We have to be happy with that after a hard stage like this.’

Skip photographs (#u489a4835-d235-5092-a8c4-2c422ac3c16a)

STAGE 10 (#ulink_549f6158-6c62-5f56-a378-41d919625573)

The race moved to the high mountains of north-east Italy to deliver the first summit finish. The climb to Altopiano del Montasio was new to the Giro – one of those supersteep peaks that Ljungqvist jokes the organisers manage to discover each year – and posed one of the hardest finishes in the race. At the toughest part of the ascent, which lasts about a kilometre, the gradient registered 20 per cent. It was a key stage, the day when the big GC contenders came up against the climbers, with a major reshuffle expected in the overall standings.

This is where Team Sky’s Colombian riders – Rigoberto Uran and Sergio Henao – come into their element. Both have superb all-round qualities, but explosive climbing is their speciality. While most professional cyclists spend short periods in altitude training camps (where the body adapts to the relative lack of oxygen by increasing the mass of red blood cells that oxygenate the body), many Colombians have a natural physiological advantage as a result of their country’s topography.

It was no surprise that it was a Colombian 1–2 on the podium at the end of the day, after a stunning solo victory from Urán, who powered off from 8km to go, without getting out of the saddle. Wiggins, meanwhile, saw his team-mate off, but lost touch as the gradient ramped up in that final stretch. He maintained fourth place overall, 1 second behind Urán, losing further time to Nibali.

‘I love the mountains, particularly when I look around on a climb and see how much the other riders are suffering!’ said Urán. ‘Every rider is picked with his own job to do. We all know what our job is and once we have done it we drop back at certain pre-planned points. On a high-mountain stage, once the group is down to the 30 best riders, the pain starts and then I attack. I have other attributes, but I really love climbing.’

‘In the morning meeting it was Brad’s idea to be aggressive with Rigo, and Brad would follow,’ said Danny Pate. ‘We would ride the Sky way, on the forefront, and everyone would just pack up. The plan was to be aggressive and, I guess, progressive. You want to have your own plan and execute it.’

‘It was an incredible day, the teamwork was strong and we rode hard all day to put pressure on other teams,’ said Urán. ‘The plan was for me to attack at 7 to 8km out. Looking at the stage profile card, I knew that meant 30 minutes of effort, giving my maximum at gradient, right on the limit. I knew if I scaled my effort according to the distance, I could win. Over the radio, they were telling me the finish line was close, but when you hear that, it somehow stretches out! You feel you’re never going to reach it. When I actually saw the finish, I felt energy flood through me, even though I was riding off the scale. It was an unforgettable moment. After three Grand Tours, it was a massive thing to win my first stage, an emotional day for me – and for the team, after all the expectations on Bradley and the problems we were encountering. To pull off that win was a special moment.’

‘Rigo’s win was a huge boost,’ said Pate. ‘You finish a tough day with a result like that and it makes you look forward to the next one. If you remember you won on the last hard day, you almost start to look forward to them.’