По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 2: Reader’s Guide PART 1

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

SHORTER BIOGRAPHIES

An ever-increasing number of shorter, illustrated biographies of Tolkien have also appeared, intended for younger (or more casual adult) readers. These include J.R.R. Tolkien: Man of Fantasy by Russell Shorto (1988); J.R.R. Tolkien: Master of Fantasy by David R. Collins (1992), made over in 2005 as J.R.R. Tolkien, significantly shortened and simplified, cluttered with inane sidebars (‘It’s a Fact!’), and injected with references to the Peter Jackson films of The Lord of the Rings (*Adaptations); Myth Maker: J.R.R. Tolkien by Anne E. Neimark (1996); J.R.R. Tolkien: The Man Who Created The Lord of the Rings by Michael Coren (2001); J.R.R. Tolkien: Creator of Languages and Legends by Doris Lynch (2003); J.R.R. Tolkien by Neil Heims (2004); The Importance of J.R.R. Tolkien by Stuart P. Levine (2004); J.R.R. Tolkien: Master of Imaginary Worlds by Edward Willett (2004); J.R.R. Tolkien by Vic Parker (2006); J.R.R. Tolkien by Jill C. Wheeler (2009); J.R.R. Tolkien by Mark Horne (2011); J.R.R. Tolkien by Alexandra Wallner (2011), a picture book in which Tolkien’s life is treated like a board game; and Caroline McAlister, John Ronald’s Dragons: The Story of J.R.R. Tolkien (2017). Each suffers to a degree from factual errors and (even allowing that these are necessarily short books) serious omissions; and many of the authors embroider or exaggerate for dramatic effect. Of these, Collins’ 1992 account is to be preferred for balance and accuracy, but the young person who has read The Lord of the Rings successfully should be equally capable of reading Carpenter’s Biography, and with greater reward.

CONSIDERATIONS IN TOLKIEN BIOGRAPHY

Almost all biographical writings about Tolkien rely to some degree on Carpenter, usually supplemented by reference to Tolkien’s published letters (1981). The best of the later biographies draw as well upon the large number of books and articles, by and about Tolkien, that have appeared since the Biography was published in 1977; the least of them are mere adaptations or reductions of Carpenter’s. The assiduous Tolkien biographer casts a wide net of research, but also must seek to understand what he finds, without assumptions based on his own age or culture – one finds, for instance, in some American accounts of Tolkien’s life, a lack of comprehension of English universities and their customs. It is possible to write an insightful biography without undertaking original research, relying only on existing sources (it is also possible, as we have seen in some books which claim to take a fresh approach to Tolkien’s biography, to turn the facts of his life into fiction); and yet, as shown especially by John Garth in Tolkien and the Great War and his other writings, and by the present book, important information is still to be gleaned from libraries and archives which can change the way we see Tolkien and interpret his works.

Nor can the biographer afford to be uncritical of sources. In the course of writing the Companion and Guide we discovered errors and discrepancies even in standard published works, and inconsistencies in manuscripts and recorded reminiscences. A wealth of information is to be found in a series of recordings of Tolkien’s family and friends made soon after his death by Ann Bonsor, and first broadcast on Radio Oxford in 1974; but in some of these, looking back to times long past, memory demonstrably failed. Nevill Coghill, for one, recalled how as secretary of the Exeter College Essay Club (*Societies and clubs) he had asked Tolkien to read a paper at one of their meetings. Tolkien agreed, and said that the subject of his paper would be ‘the fall of Gondolin’. Coghill remembered that he then spent weeks searching in reference books in vain to find a mention of ‘Gondolin’, not realizing that it was the name of a city in Tolkien’s mythology. Records show, however, that Coghill had not held any office in the Essay Club when Tolkien read The Fall of Gondolin (see *The Book of Lost Tales) to its members, and in fact was elected to the Club only on 27 February 1920, less than two weeks before the event.

Even Tolkien himself sometimes nodded. In referring to his lecture *On Fairy-Stories he twice gave an erroneous date for its delivery at the University of St Andrews (‘1940’ and ‘1938’, in fact 1939), and in his Foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings (1965) he wrote that the work ‘was begun soon after The Hobbit was written and before its publication in 1937’, though in fact he began the sequel between 16 and 19 December 1937, after publication of The Hobbit on 22 September 1937. The latter is clear from a reading of Letters, and yet occasionally one still sees it written in books about Tolkien that he began The Lord of the Rings before the publication of The Hobbit, uncritically accepting his misstatement of 1965.

As we state in our preface, we did not write the Companion and Guide to be a substitute for Carpenter’s Biography, nor, even now in the second edition, do we feel that our book replaces Carpenter, but rather is a different, if much more comprehensive approach, to Tolkien’s life. We would agree with John Garth’s comment that ‘with the arrival of the Companion and Guide there ought now to be no excuse, beyond sheer laziness, for other biographers to use Humphrey Carpenter’s 1977 J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography as virtually the sole source of information about Tolkien’s life, as too many have done’ (review of the Companion and Guide, Tolkien Studies 4 (2007), p. 258). On the contrary, David Bratman has suggested that the Companion and Guide, ‘while a chronology and encyclopedia, rather than a biography, instantly superseded Humphrey Carpenter’s long-standard Tolkien: A Biography as the source of first reference for biographical data on the man’ (‘The Year’s Work in Tolkien Studies 2006’, Tolkien Studies 9 (2009), p. 315).

In the present century numerous books and videos have been produced which purport to be accounts of Tolkien’s life. Some, as seen here, are genuine in their aims and have value. Others – to put it charitably – are less careful in reporting facts, indeed are largely (if not entirely) products of their author’s imagination. See further, our 2015–16 blog posts at wayneandchristina.wordpress.com titled ‘Tolkien Biographies Continued’ (i.e. since our 2006 edition).

‘Bird and Baby’ (Eagle and Child) seeOxford and environs

Birmingham and environs. Both of Tolkien’s parents came from this major manufacturing centre in the English *West Midlands, and he himself spent sixteen of his early years in or near the city. His father (*Arthur Tolkien) and paternal grandparents (see *Tolkien family) lived at ‘Beechwood’ in Church Road in the southern suburb of Moseley, while his mother *Mabel and her family (see *Suffield family) were from Kings Heath still further south. Mabel’s grandfather, John Suffield the elder, had once been a prosperous draper and hosier in Old Lamb House, Bull Street, Birmingham (demolished 1886), and other members of the family were employed in the business.

Tolkien himself came to Birmingham from *South Africa with his mother and brother at the end of April 1895; until summer 1896 they stayed at 9 Ash-field Road, Kings Heath with Mabel Tolkien’s parents and siblings. It was there in December 1895 that young Ronald Tolkien experienced his first wintry Christmas. In February 1896 his father died in Bloemfontein, and his mother decided that she and her sons should live independent of her parents’ crowded home, in the countryside where the boys could have fresh air. In summer 1896 Mabel rented a semi-detached cottage at 5 Gracewell Road (today 264a Wake Green Road) in the hamlet of *Sarehole not far to the east of Kings Heath, now part of the suburb of Hall Green. It was an idyllic setting, or became so in Tolkien’s memory, a rural paradise of fields, trees, and flowers and a working mill. But the interlude there was brief.

In September 1900 Tolkien began to attend classes at *King Edward’s School in New Street in the centre of Birmingham, some four miles distant, and at first walked most of the way between home and school since trams did not run as far as Sarehole, and Mabel could not afford train fare. It was a long walk for the family also to Sunday services at St Anne’s, the Roman Catholic church in Alcester Street, Moseley, in which Mabel had been received into the faith the previous June. In consequence, Mabel Tolkien later that September rented a small house at 214 Alcester Road, Moseley, near a tram route into the city. According to Humphrey Carpenter, however, ‘no sooner had [the family] settled than they had to move: the house was to be demolished to make room for a fire-station’ (Biography, p. 25). At the end of 1900 or the beginning of 1901 Mabel, Ronald, and his brother *Hilary moved once again, to 86 West-field Road, Kings Heath. Mabel chose their new home because it was close to the Roman Catholic church of St Dunstan, then a building of wood and corrugated iron on the corner of Westfield Road and Station Road. Tolkien now first came into contact with the Welsh *language, in names on passing coal-trucks.

Readers of Carpenter’s Biography, or of later *biographies which closely follow Carpenter, will have a mental picture of the Birmingham of Tolkien’s youth as purely an industrial city. Writing of Tolkien’s brief time in Moseley, Carpenter says:

Home life was very different [in the second half of 1900] from what [Ronald] had known at Sarehole. His mother had rented a small house on the main road in the suburb of Moseley, and the view from the windows was a sad contrast to the Warwickshire countryside: trams struggling up the hill, the drab faces of passers-by, and in the distance the smoking factory chimneys of Sparkbrook and Small Heath. To Ronald the Moseley house remained in memory as ‘dreadful’. [p. 25]

It is true to say that Birmingham was a centre of the Industrial Revolution, known for its metal-working, and that it was a focus of the railways. A contemporary observer called it ‘a metropolis of machinery … exceedingly interesting as a consistently developed exemplification of the nineteenth-century spirit’ (Harry Quilter, What’s What (1902), p. 236). Inevitably there was pollution and traffic, and substantial development was underway. But in residential suburbs such as Moseley factory smoke was less pronounced, and local industry supported the city’s excellent schools and museums, including an art gallery with works by the Pre-Raphaelites (see *Art). As Maggie Burns has pointed out (‘“… A Local Habitation and a Name …”’, Mallorn 50 (Autumn 2010)),

maps of the time [of Tolkien’s youth], in addition to contemporary descriptions by people living in Birmingham suburbs, give a different picture. The parts of Birmingham where Tolkien lived had parks, streams, gardens and trees. Birmingham was and is a city of trees. …

The Birmingham described as wasteland by Carpenter in the 1970s was not the Birmingham that Tolkien knew around 1900. Much of the town had been rebuilt during the 20 years before Tolkien arrived there as a three-year-old in 1985. There were many new and imposing buildings. …

The countryside was not distant from the city as implied in some Tolkien biographies. Sarehole was [only] four miles from the centre of Birmingham. … Horses were in the city as well as in the country.

In 1900 trams were still drawn by horses and cars were a rarity. [pp. 26–7]

Moseley in fact, situated on high ground, was relatively free from factory smoke – as a contemporary guidebook description put it, even more so than Edgbaston, which was considered the most fashionable suburb of Birmingham – and it was on the edge of the countryside, not far distant from Sarehole. In his poem *The Battle of the Eastern Field (1911, a parody of Macaulay) Tolkien writes of ‘Mosli’s [Moseley’s] emerald sward’ (and of ‘Edgbastonia’s [Edgbaston’s] ancient homes’). Kings Heath was to the south of Moseley, and although the Tolkiens’ home there was in a noisy and undoubtedly smoky location, near the railway with its coal-powered engines, the slopes of the cutting behind the house were covered with grass and flowers, and (as today) there were fields on the other side of the line.

Dissatisfied with St Dunstan’s, Mabel looked for a new place of worship and found the *Birmingham Oratory in the suburb of Edgbaston. In early 1902 she and her sons moved to 26 Oliver Road, Edgbaston (the house no longer exists), conveniently near the Oratory church and its attached grammar school, St Philip’s. There they stayed until April 1904, when Mabel was taken into hospital suffering from diabetes. Her boys lived for a while apart from their mother, until they were reunited in the hamlet of *Rednal, a few miles from the centre of Birmingham to the south-west, and were together until Mabel’s death on 14 November 1904.

Immediately after the loss of their mother Ronald and Hilary stayed with Laurence Tolkien, one of their father’s brothers, at Dunkeld, Middleton Hall Road, Kings Norton. By January 1905 *Father Francis Morgan, the priest whom Mabel had named her sons’ guardian, placed them instead with their Aunt Beatrice Suffield at 25 Stirling Road, Edgbaston, not far from the Oratory. Their room was on the top floor.

Early in 1908, life with Aunt Beatrice having proved unhappy for the boys, Father Francis moved them to 37 Duchess Road, Edgbaston, the home of the Faulkner family. Ronald and Hilary had a rented room on the second floor; on the first floor was another lodger, Edith Bratt (*Edith Tolkien), with whom they became friends. Edith played the piano and accompanied soloists at musical evenings given by Mrs Faulkner, but was discouraged from practising. Gradually Ronald and Edith fell in love. When their clandestine relationship came to the attention of Father Francis late in 1909 he took steps to end it. Ronald and Hilary were now removed to new lodgings with Thomas and Julia MacSherry at 4 Highfield Road, Edgbaston, at which address Tolkien lived until going up to Exeter College, *Oxford in October 1911.

During his years at King Edward’s School Tolkien became familiar with central Birmingham and with some of its merchants. Among these were Cornish’s bookshop in New Street, which Tolkien explored for books on *Philology; E.H. Lawley & Sons at 24 New Street, a jeweller at which Ronald and Edith bought each other presents in January 1910 (see Life and Legend, fig. 25); and Barrow’s Stores in Corporation Street (north from New Street), until the 1960s a flourishing grocer’s which had its origin in a shop founded in 1824 by John Cadbury (of Cadbury’s cocoa). An engraving of Barrow’s Stores is reproduced in The Tolkien Family Album, p. 26. Tolkien and some of his friends at King Edward’s School, having formed a Tea Club, met regularly in Barrow’s Tea Room. *Christopher Wiseman recalled that ‘in the Tea Room there was a sort of compartment, a table for six, between two large settles, quite secluded; and it was known as the Railway Carriage. It became a favourite place for us, and we changed our title to the Barrovian Society after Barrow’s Stores’ (quoted in Biography, p. 46). The group ultimately combined the names Tea Club and Barrovian Society, abbreviated as *T.C.B.S.

On 9 November 1916, having contracted trench fever during military service in France, Tolkien was admitted to the First Southern General Hospital, a converted facility of over one thousand beds at the then newly built Birmingham University in Edgbaston. He was a patient there until 9 December 1916, when he was able to take sick leave. During these few weeks in hospital he may have begun to write *The Book of Lost Tales.

Referring to Sarehole, Tolkien wrote in a draft letter to Michael Straight that he had been ‘brought up in an “almost rural” vilage of Warwickshire on the edge of the prosperous bourgeoisie of Birmingham’ (probably January or February 1956, Letters, p. 235). Maggie Burns has suggested that some of Tolkien’s relatives, many of whom lived in Moseley, could be described as ‘prosperous bourgeoisie’. Arthur Tolkien’s sister Mabel lived with her husband, Thomas Mitton, in ‘Abbotsford’, a large house with a garden in Wake Green Road in Moseley. His grandparents on his mother’s side lived off Wake Green Road in Cotton Lane, from 1904 to 1930; and on his father’s side, his grandparents lived in Church Road, also off Wake Green Road, until 1900. Mabel Tolkien’s sister’s family, the Incledons (*Incledon family), had what Maggie Burns describes as ‘a luxurious new house’ in Chantry Road, Moseley, ‘with a garden running down to a private park’ (‘“… A Local Habitation and a Name …”’, p. 27).

At least in the period 1913–15, Tolkien occasionally visited his friend *Robert Q. Gilson at his family home in Marston Green, near Birmingham to the east.

When Tolkien lived in Birmingham, most of the buildings in the city centre were still of recent vintage, having been built or re-built within the previous fifty years. But some were replaced within the next half-century, to Tolkien’s dismay. On 3 April 1944, having recently visited the new King Edward’s School in Edgbaston Park Road, he wrote to his son *Christopher: ‘Except for one patch of ghastly wreckage (opp[osite] my old school’s site) [Birmingham] does not look much damaged: not by the enemy [in wartime bombing raids]. The chief damage has been the growth of great flat featureless modern buildings. The worst of all is the ghastly multiple-store erection on the old site’ (Letters, p. 70).

Two towers in Birmingham have been suggested as the inspiration for those in the *Lord of the Rings volume title The Two Towers. One is Perrot’s Folly, built in 1758 by John Perrot and used by Birmingham University as a weather observatory from the 1880s to the 1970s; the other is the chimney of the Edgbaston Water Works. It hardly seems necessary, however, for Tolkien to have based any of the towers in The Lord of the Rings – there are more than two – specifically on any of the towers he may have seen in Birmingham – there are more than these two – or indeed on any particular tower, when such constructions are common in European architecture and in literature.

Contemporary maps and descriptions of the places in and near Birmingham where Tolkien lived, and recent photographs of his former homes, are reproduced in the booklet Tolkien’s Birmingham by Patricia Reynolds (1992) and in Robert S. Blackham, The Roots of Tolkien’s Middle Earth (2006; see also his ‘Tolkien’s Birmingham’, Mallorn 45 (Spring 2008)). Photographs of Tolkien homes are included also in the article on Tolkien in Some Moseley Personalities, Volume I (1991). Moseley and Kings Heath on Old Picture Postcards, compiled by John Marks (1991), is a useful collection of photographs of those places dating from Tolkien’s years in Birmingham. Additional resources are Hall Green, compiled by Michael Byrne (1996); Edgbaston, compiled by Martin Hampson (1999); and Christine Ward-Penny, Catholics in Birmingham (2004). Also see further, Maggie Burns, ‘Faces and Places: John Suffield’, Connecting Histories website; and pages on the website of the Library of Birmingham, www.libraryofbirmingham.com/tolkien.

Birmingham Oratory. The Oratory Order begun in Rome by St Philip Neri was formally recognized by Pope Gregory XIII in 1575. Its main mission is preaching, prayer, and the administration of the sacraments. John Henry Newman, later Cardinal Newman, introduced the order into England by founding the Oratorian Congregation in Birmingham in 1848. In 1852 the community moved to Hagley Road in the suburb of Edgbaston, where a house and church were built. (Their first chapel, in Alcester Road, Moseley, was replaced by St Anne’s Church, which Tolkien, his mother, and his brother attended for a while; see *Birmingham and environs.) In 1859 Newman also founded St Philip’s, a grammar school attached to the Oratory Church. The church was later extended, and beginning in 1903 a new building, designed by E. Doran Webb, was constructed over the old, in the style of the Church of San Martino in Rome as Newman had originally desired. A photograph of the old church is reproduced in The Tolkien Family Album, p. 23.

Tolkien’s mother *Mabel, a recent convert to Catholicism seeking a satisfactory place of worship, discovered the Oratory in 1901, and early in 1902 moved with her sons to Edgbaston. *Father Francis Morgan, a member of the Oratory community then carrying out the duties of parish priest, became a close family friend and after Mabel’s death the guardian of her children. Tolkien and his brother *Hilary briefly went to St Philip’s School, because it offered a Catholic education at low cost and was convenient to home, until it became clear that it could not provide the quality of learning that young Ronald Tolkien needed. (Tolkien returned to *King Edward’s School, which he had attended earlier; Hilary joined him after a period of tuition by their mother.)

As wards of Father Francis the Tolkien boys spend much of their time between 1904 and 1911 at the Oratory. Tolkien later recalled that he was ‘virtually a junior inmate of the Oratory house, which contained many learned fathers (largely “converts”). Observance of religion was strict. Hilary and I were supposed to, and usually did, serve Mass before getting on our bikes to go to [King Edward’s] school in New Street’ (letter to his son Michael, 1967, Letters, p. 395). In 1909 they also were in charge of three patrols of Boy Scouts under the aegis of the parish. In these years Ronald and Hilary would have witnessed the transformation of the Oratory Church from old to new.

Blackwell, Basil Henry (1889–1984). Basil Blackwell was educated at Merton College, *Oxford and trained at Oxford University Press in London. From 1913, for six years, he worked with his father’s publishing firm, B.H. Blackwell, which published Tolkien’s early poem *Goblin Feet in *Oxford Poetry 1915; the annual Oxford Poetry volumes, begun in 1913, were Basil’s idea. Although Tolkien came to dislike Goblin Feet, he expressed gratitude to Blackwell as his first publisher (silently omitting his schoolboy publications in the Chronicle of *King Edward’s School, Birmingham). In 1919 Blackwell became an independent publisher, and in succeeding years expanded his operation. In 1924, on his father’s death, he became head of the family bookselling business as well. During his long life he also presided over trade and scholarly associations, and held civic posts in Oxford. He received numerous honours, including a knighthood in 1956 and an honorary fellowship at Merton College in 1959.

For a few years, from 1926, Blackwell and Tolkien were neighbours in North Oxford, at 20 and 22 Northmoor Road respectively. When in 1929 Blackwell vacated no. 20, Tolkien purchased it; he moved his family into the comparatively larger house in 1930. Tolkien was also a frequent customer of Blackwell’s Bookshop in Broad Street, *Oxford, where by 1942 his account was seriously overextended. Blackwell offered to reduce Tolkien’s debt by publishing his translation of *Pearl (which existed in a finished form since 1926) and applying the translator’s payment against his account. The work was set in type, but Tolkien failed to write more than rough notes for an introduction, and in the end Blackwell abandoned the project with remarkable grace.

See also Rita Ricketts, Adventurers All: Tales of Blackwellians, of Books, Bookmen, and Reading and Writing Folk (2002), and Ricketts, Scholars, Poets & Radicals: Discovering Forgotten Lives in the Blackwell Collections (2015).

Bliss, Alan Joseph (1921–1985). Having received his B.A. at King’s College, University of London, Alan Bliss studied at *Oxford for a B.Litt. from 1946 to 1948. His thesis, supervised by Tolkien, was an edition of the Middle English poem *Sir Orfeo. In Hilary Term 1948 he delivered a series of lectures on that work, and in Trinity Term 1948 lectured on ‘The West Saxon Dialect in Middle English’, on both occasions acting on Tolkien’s behalf. Bliss later taught at Malta and Istanbul before taking up appointments in Old and Middle English at University College, Dublin. He succeeded to the Chair of Old and Middle English at Dublin in 1974.

Revised for publication, his Sir Orfeo appeared in 1954 in the *Oxford English Monographs, of which Tolkien was a general editor. In his introduction to Sir Orfeo Bliss thanks Tolkien, ‘whose penetrating scholarship is an inspiration to all who have worked with him’ (p. vi). Among other works Bliss wrote or edited are The Metre of Beowulf (1957); A Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases in Current English (1966); Spoken English in Ireland, 1600–1740 (1979); and *Finn and Hengest: The Fragment and the Episode (1982), an edition of Tolkien’s lectures on the ‘Finnesburg Fragment’ and the related episode in *Beowulf. In his preface to Finn and Hengest Bliss relates that in 1966 Tolkien had offered him all of his material on the story, to use in preparing for publication a paper on ‘Hengest and the Jutes’. Bliss did not receive the papers until 1979, however, after Tolkien’s death; and when he read Tolkien’s lectures ‘it became obvious to me that I could never make use of his work in any work of my own: not only had he anticipated nearly all my ideas, but he had gone far beyond them in directions which I had never considered’ (p. v). Bliss agreed instead, in response to a proposal by *Christopher Tolkien, to prepare Tolkien’s lectures for publication, with added notes and comments.

Bliss contributed an essay, ‘The Appreciation of Old English Metre’, to the Festschrift *English and Medieval Studies Presented to J.R.R. Tolkien on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday (1962), and another, ‘Beowulf Lines 3074–3075’, to J.R.R. Tolkien, Scholar and Storyteller: Essays in Memoriam, ed. Mary Salu and Robert T. Farrell (1979).

BloemfonteinseeSouth Africa

Blomfield, Joan ElizabethseeTurville-Petre, Joan Elizabeth

‘The Bodleian Declensions’. The earliest extant chart of noun inflections in Quenya (*Languages, Invented), edited with analysis by Patrick Wynne, Christopher Gilson, and Carl F. Hostetter, published in Vinyar Tengwar 28 (March 1993), pp. 8–34.

The chart is so called because it was found among Tolkien’s manuscripts at the Bodleian Library, Oxford (*Libraries and archives), neatly written in ink c. November 1936 on one page within a draft of Beowulf and the Critics (*Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics). Like *‘The Plotz Declension’, the Bodleian manuscript is concerned with a Quenya word for ‘ship’, here kirya, but also with pole (probably ‘oat’).

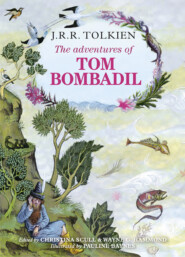

Bombadil Goes Boating. Poem, first published in *The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book (1962), pp. 17–23.

Bombadil Goes Boating is a sequel of sorts to *The Adventures of Tom Bombadil. The new poem follows merry Tom as he rows a boat down stream on an autumn day, intending to meet his friend Farmer Maggot (from *The Lord of the Rings). Along the way a wren, a kingfisher, an otter, a swan, the hobbit-folk of Hays-end and Breredon, and finally Farmer Maggot scold with insults, but Tom gives back as good as he gets. At last Tom goes to Maggot’s home: there ‘songs they had and merry tales, the supping and the dancing’, and they swap ‘all the tidings / from Barrow-downs to Tower Hills’. Tom returns home unseen. Later the boat he left at Grindwall is taken back up the Withywindle by Otter-folk, the Old Swan, and the King’s fisher, but they forget to bring the oars.

Tolkien developed Bombadil Goes Boating for the 1962 volume from an earlier, isolated poem, or fragment of a poem, which he called the ‘germ of Tom Bombadil’ (‘Ho! Tom Bombadil / Whither are you going / With John Pompador / Down the River rowing?’); this was first published in *The Return of the Shadow (1988), pp. 115–16, and printed also in the expanded edition of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book (2014), pp. 138–9.

In the process, Tolkien called the work variously The Fliting of Tom Bombadil, The Merry Fliting of Tom Bombadil, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil II: The Merry Fliting before settling on its final, more prosaic title. Fliting, from the Old English for ‘strive’ or ‘quarrel’, refers to a contest of insults, such as the exchange in *Beowulf between Beowulf and Unferth before Beowulf faces Grendel. The insults traded by Tom and the others in Bombadil Goes Boating parallel his challenges in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, but here the exchanges are light and laced with humour, without the menace that underlies the earlier poem (‘Ho there! beggarman tramping in the Marish!’ ‘Well, well, Muddy-feet! From one that’s late for meeting /away back by the Mithe that’s a surly greeting!’).

In a letter to his publisher *Rayner Unwin on 12 April 1962 Tolkien allowed that an understanding of Bombadil Goes Boating required a knowledge of The Lord of the Rings: ‘at any rate it performs the service of further “integrating” Tom with the world of the Lord of the Rings into which he was inserted.’ He felt that it tickled his ‘pedantic fancy’ because it contains an echo of the Norse Nibelung legends and ‘one of the lines comes straight … from The Ancrene Wisse [*Ancrene Riwle]’ (Letters, p. 315). On 1 August 1962 he wrote to *Pauline Baynes that he had placed the fictional time of the poem ‘to the days of growing shadow’, that is, before Frodo’s departure from Hobbiton in The Lord of the Rings (Letters, p. 319).

The Book of Lost Tales. Series of tales in which a traveller, Eriol (*Eriol and Ælfwine), having come to the Lonely Island (or Isle) of the Elves, Tol Eressëa, is told of the Creation of the World and the history of the Elves until the time of his arrival in their midst. For convenience in *The History of Middle-earth, the tales were published in two volumes, *The Book of Lost Tales, Part One (1983) and *The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two (1984): these follow the chronology of events within the mythology, but not the order of writing of the tales, nor necessarily Tolkien’s original plan for the order of their telling. Each volume also includes descriptions and commentary by Christopher Tolkien, poems by Tolkien related to the tales, and appendices on the meanings of names within his invented languages. In the Reader’s Guide summaries of the tales and consideration of their place in the evolution of the mythology are dealt with in relation to the chapters of the published *Silmarillion (1977); these are listed, with cross-references, in the separate entries for Part One and Part Two.

HISTORY