По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

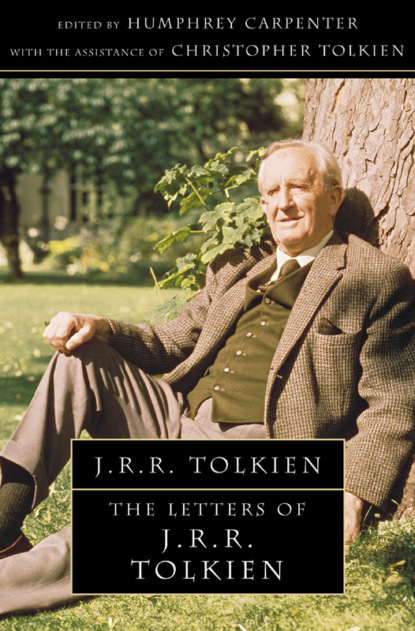

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

88 From a letter to Christopher Tolkien

28 October 1944 (FS 58)

This empty year is fading into a dull grey mournful darkness: so slow-footed and yet so swift and evanescent. What of the new year and the spring? I wonder.

89 To Christopher Tolkien

7–8 November 1944 (FS 60)

20 Northmoor Road, Oxford

. . . . Your reference to the care of your guardian angel makes me fear that ‘he’ is being specially needed. I dare say it is so. . . . . It also reminded me of a sudden vision (or perhaps apperception which at once turned itself into pictorial form in my mind) I had not long ago when spending half an hour in St Gregory’s before the Blessed Sacrament when the Quarant’ Ore

was being held there. I perceived or thought of the Light of God and in it suspended one small mote (or millions of motes to only one of which was my small mind directed), glittering white because of the individual ray from the Light which both held and lit it. (Not that there were individual rays issuing from the Light, but the mere existence of the mote and its position in relation to the Light was in itself a line, and the line was Light). And the ray was the Guardian Angel of the mote: not a thing interposed between God and the creature, but God’s very attention itself, personalized. And I do not mean ‘personified’, by a mere figure of speech according to the tendencies of human language, but a real (finite) person. Thinking of it since – for the whole thing was very immediate, and not recapturable in clumsy language, certainly not the great sense of joy that accompanied it and the realization that the shining poised mote was myself (or any other human person that I might think of with love) – it has occurred to me that (I speak diffidently and have no idea whether such a notion is legitimate: it is at any rate quite separate from the vision of the Light and the poised mote) this is a finite parallel to the Infinite. As the love of the Father and Son (who are infinite and equal) is a Person, so the love and attention of the Light to the Mote is a person (that is both with us and in Heaven): finite but divine: i.e. angelic. Anyway, dearest, I received comfort, part of which took this curious form, which I have (I fear) failed to convey: except that I have with me now a definite awareness of you poised and shining in the Light – though your face (as all our faces) is turned from it. But we might see the glimmer in the faces (and persons as apprehended in love) of others. . . . .

On Sunday Prisca and I cycled in wind and rain to St Gregory’s. P. was battling with a cold and other disability, and it did not do her much immediate good, though she’s better now; but we had one of Fr. C’s best sermons (and longest). A wonderful commentary on the Gospel of the Sunday (healing of the woman and of Jairus’ daughter), made intensely vivid by his comparison of the three evangelists. (P. was espec. amused by his remark that St Luke being a doctor himself did not like the suggestion that the poor woman was all the worse for them, so he toned that bit down). And also by his vivid illustrations from modern miracles. The similar case of a woman similarly afflicted (owing to a vast uterine tumour) who was cured instantly at Lourdes, so that the tumour could not be found, and her belt was twice too large. And the most moving story of the little boy with tubercular peritonitis who was not healed, and was taken sadly away in the train by his parents, practically dying with 2 nurses attending him. As the train moved away it passed within sight of the Grotto. The little boy sat up. ‘I want to go and talk to the little girl’ – in the same train there was a little girl who had been healed. And he got up and walked there and played with the little girl; and then he came back, and he said ‘I’m hungry now’. And they gave him cake and two bowls of chocolate and enormous potted meat sandwiches, and he ate them! (This was in 1927). So Our Lord told them to give the little daughter of Jairus something to eat. So plain and matter of fact: for so miracles are. They are intrusions (as we say, erring) into real or ordinary life, but they do intrude into real life, and so need ordinary meals and other results. (Of course Fr. C could not resist adding: and there was also a Capuchin Friar who was mortally ill, & had eaten nothing for years, and he was cured, and he was so delighted about it that he rushed off and had two dinners, and that night he had not his old pains but an attack of plain ordinary indigestion). But at the story of the little boy (which is a fully attested fact of course) with its apparent sad ending and then its sudden unhoped-for happy ending, I was deeply moved and had that peculiar emotion we all have – though not often. It is quite unlike any other sensation. And all of a sudden I realized what it was: the very thing that I have been trying to write about and explain – in that fairy-story essay that I so much wish you had read that I think I shall send it to you. For it I coined the word ‘eucatastrophe’: the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears (which I argued it is the highest function of fairy-stories to produce). And I was there led to the view that it produces its peculiar effect because it is a sudden glimpse of Truth, your whole nature chained in material cause and effect, the chain of death, feels a sudden relief as if a major limb out of joint had suddenly snapped back. It perceives – if the story has literary ‘truth’ on the second plane (for which see the essay) – that this is indeed how things really do work in the Great World for which our nature is made. And I concluded by saying that the Resurrection was the greatest ‘eucatastrophe’ possible in the greatest Fairy Story – and produces that essential emotion: Christian joy which produces tears because it is qualitatively so like sorrow, because it comes from those places where Joy and Sorrow are at one, reconciled, as selfishness and altruism are lost in Love. Of course I do not mean that the Gospels tell what is only a fairy-story; but I do mean very strongly that they do tell a fairy-story: the greatest. Man the story-teller would have to be redeemed in a manner consonant with his nature: by a moving story. But since the author if it is the supreme Artist and the Author of Reality, this one was also made to Be, to be true on the Primary Plane. So that in the Primary Miracle (the Resurrection) and the lesser Christian miracles too though less, you have not only that sudden glimpse of the truth behind the apparent Anankê

of our world, but a glimpse that is actually a ray of light through the very chinks of the universe about us. I was riding along on a bicycle one day, not so long ago, past the Radcliffe Infirmary, when I had one of those sudden clarities which sometimes come in dreams (even anaesthetic-produced ones). I remember saying aloud with absolute conviction: ‘But of course! Of course that’s how things really do work’. But I could not reproduce any argument that had led to this, though the sensation was the same as having been convinced by reason (if without reasoning). And I have since thought that one of the reasons why one can’t recapture the wonderful argument or secret when one wakes up is simply because there was not one: but there was (often maybe) a direct appreciation by the mind (sc. reason) but without the chain of argument we know in our time-serial life. However that’s as may be. To descend to lesser things: I knew I had written a story of worth in ‘The Hobbit’ when reading it (after it was old enough to be detached from me) I had suddenly in a fairly strong measure the ‘eucatastrophic’ emotion at Bilbo’s exclamation: ‘The Eagles! The Eagles are coming!’. . . . And in the last chapter of The Ring that I have yet written I hope you’ll note, when you receive it (it’ll soon be on its way) that Frodo’s face goes livid and convinces Sam that he’s dead, just when Sam gives up hope.

And while we are still, as it were, on the porch of St Gregory’s on Sunday 5 Nov. I saw the most touching sight there. Leaning against the wall as we came out of church was an old tramp in rags, something like sandals tied on his feet with string, an old tin can on one wrist, and in his other hand a rough staff. He had a brown beard, and a curiously ‘clean’ face, with blue eyes, and he was gazing into the distance in some rapt thought not heeding any of the people, cert. not begging. I could not resist the impulse of offering him a small alms, and he took it with grave kindliness, and thanked me courteously, and then went back to his contemplation. Just for once I rather took Fr. C. aback by saying to him that I thought the old man looked a great deal more like St Joseph than the statue in the church – at any rate St Joseph on the way to Egypt. He seems to be (and what a happy thought in these shabby days, where poverty seems only to bring sin and misery) a holy tramp! I could have sworn it anyway, but P. says Betty

told her that he had been at the early mass, and had been to communion, and his devotion was plain to see, so plain that many were edified. I do not know just why, but I find that immensely comforting and pleasing. Fr. C says he turns up about once a year.

This is becoming a very peculiar letter! I hope it does not seem all very incomprehensible; for events have directed me to topics that are not really treatable without erasions and re-writings, impossible in air letters!. . . . Let us finish the diary. . . . . On Monday (I think) a hen died – one of the bantam twins; cert. it was buried that day. Also I saw C.S.L. and C.W. from about 10.40 to 12.50, but can recollect little of the feast of reason and flow of soul, partly because we all agree so. It was a bright morning, and the mulberry tree in the grove just outside C.S.L.’s window shone like fallow gold against colbalt blue sky. But the weather worsened again, and in the afternoon I did one of the foulest jobs. I grease-banded all the trees (apple) tying 16 filthy little pantelettes on. It took 2 hours, and nearly as long to get the damned stuff off hands and implements. I neglected it last year, and so lost ½ a glorious crop to ‘moth’. It will be like this ‘cacocatastrophic’ fallen world, if next year there ain’t no blossom. Tuesday: lectures and a brief glimpse, at ‘The Bird’, of the Lewis Bros. and Williams. The Bird is now gloriously empty, with improved beer, and a landlord wreathed in welcoming smiles! He lights a special fire for us!. . . .

A propos of yr. reminder about ‘Lord Nelson’ – it was in the preliminary meeting to form a United Christian Council – he’s always about. I forgot to tell you that at Gielgud’s ‘Hamlet’ he seized on a quiet moment to yell from the Dress Circle ‘A very fine performance, and I’m enjoying it very much, but cut out the swear-words!’ He did the same at the Playhouse. He was nearly lynched in the New Theatre. But he goes on his odd way. . . . .

Your own Father.

90 To Christopher Tolkien

24 November 1944 (FS 64)

20 Northmoor Road, Oxford

My dearest, there has been a splendid flow of letters from you, since I last wrote. . . . . We were most amused by your account of the Wings ceremony. I wonder how the ‘native band’ enjoyed being whizzed through the air! I also wondered how you came to have seen and to have remembered the quotation from the Exeter Book Gnomics – which (though I had not thought of it before) does cert. provide a most admirable plea in defence of singing in one’s bath. It cheered me a lot to see a bit of Anglo-Saxon, and I hope indeed that you’ll soon be able to return and perfect your study of that noble idiom. As the father said to his son: ‘Is nu fela folca þætte fyrngewntu healdan wille, ac him hyge brosnað.’ Which might be a comment on the crowding of universities and the decline of wit. ‘There is now a crowd of folks that want to get hold of the old documents, but their wits are decaying!’ I have to teach or talk about Old English to such a lot of young persons who simply are not equipped by talent or character to grasp it or profit by it. . . . . Yesterday 2 lectures, re-drafting findings of Committee on Emergency Exams. . . . and then a great event: an evening Inklings. I reached the Mitre at 8 where I was joined by C.W. and the Red Admiral (Havard), resolved to take fuel on board before joining the well-oiled diners in Magdalen (C.S.L. and Owen Barfield). C.S.L. was highly flown, but we were also in good fettle; while O.B. is the only man who can tackle C.S.L. making him define everything and interrupting his most dogmatic pronouncements with subtle distinguo’s. The result was a most amusing and highly contentious evening, on which (had an outsider eavesdropped) he would have thought it a meeting of fell enemies hurling deadly insults before drawing their guns. Warnie was in excellent majoral form. On one occasion when the audience had flatly refused to hear Jack discourse on and define ‘Chance’, Jack said: ‘Very well, some other time, but if you die tonight you’ll be cut off knowing a great deal less about Chance than you might have.’ Warnie: ‘That only illustrates what I’ve always said: every cloud has a silver lining.’ But there was some quite interesting stuff. A short play on Jason and Medea by Barfield, 2 excellent sonnets sent by a young poet to C.S.L.; and some illuminating discussion of ‘ghosts’, and of the special nature of Hymns (CSL has been on the Committee revising Ancient and Modern). I did not leave till 12.30, and reached my bed about 1 a.m. this morn. . . . .

Your own father.

91 To Christopher Tolkien

29 November 1944

20 Northmoor Road, Oxford

My dearest,

Here is a small consignment of ‘The Ring’: the last two chapters that have been written, and the end of the Fourth Book of that great Romance, in which you will see that, as is all too easy, I have got the hero into such a fix that not even an author will be able to extricate him without labour and difficulty. Lewis was moved almost to tears by the last chapter. All the same, I chiefly want to hear what you think, as for a long time now I have written with you most in mind.

I see from my Register that I sent 3 chapters off on October 14th, and another 2 on October 25th. Those must have been: Herbs and Stewed Rabbit; Faramir; and The Forbidden Pool; and Journey to the Crossroads; and the Stairs of Kirith Ungol. The first lot should have reached you by now, I hope about your birthday; the second should soon come; and I hope this lot will get to you early in the New Year. I eagerly await your verdict. Very trying having your chief audience Ten Thousand Miles away, on or off The Walloping Window-blind. Even more trying for the audience, doubtless, but authors, qua authors, are a hopelessly egotist tribe. Book Five and Last opens with the ride of Gandalf to Minas Tirith, with which The Palantir, last chapter of Book Three closed. Some of this is written or sketched. Then should follow the raising of the siege of Minas Tirith by the onset of the Riders of Rohan, in which King Theoden falls; the driving back of the enemy, by Gandalf and Aragorn, to the Black Gate; the parley in which Sauron shows various tokens (such as the mithril coat) to prove that he has captured Frodo, but Gandalf refuses to treat (a horrible dilemma, all the same, even for a wizard). Then we shift back to Frodo, and his rescue by Sam. From a high place they see all Sauron’s vast reserves loosed through the Black Gate, and then hurry on to Mount Doom through a deserted Mordor. With the destruction of the Ring, the exact manner of which is not certain – all these last bits were written ages ago, but no longer fit in detail, nor in elevation (for the whole thing has become much larger and loftier) – Baraddur crashes, and the forces of Gandalf sweep into Mordor. Frodo and Sam, fighting with the last Nazgul on an island of rock surrounded by the fire of the erupting Mount Doom, are rescued by Gandalf’s eagle; and then the clearing up of all loose threads, down even to Bill Femy’s pony, must take place. A lot of this work will be done in a final chapter where Sam is found reading out of an enormous book to his children, and answering all their questions about what happened to everybody (that will link up with his discourse on the nature of stories in the Stairs of Kirith Ungol).

But the final scene will be the passage of Bilbo and Elrond and Galadriel through the woods of the Shire on their way to the Grey Havens. Frodo will join them and pass over the Sea (linking with the vision he had of a far green country in the house of Tom Bombadil). So ends the Middle Age and the Dominion of Men begins, and Aragom far away on the throne of Gondor labours to bring some order and to preserve some memory of old among the welter of men that Sauron has poured into the West. But Elrond has gone, and all the High Elves. What happens to the Ents I don’t yet know. It will probably work out very differently from this plan when it really gets written, as the thing seems to write itself once I get going, as if the truth comes out then, only imperfectly glimpsed in the preliminary sketch. . . . .

All the love of your own father.

92 From a letter to Christopher Tolkien

18 December 1944 (FS 68)

Your news of yourself does not in some ways add to my equanimity: a dangerous trade, but may God keep you, dear boy; but as you seem to be enjoying part of it more than anything up to now, I take comfort in that. I should feel happier, if your time was better organized, so that you could get reasonable rest: training by straining seems irrational. But I fear an Air Force is a fundamentally irrational thing per se. I could wish dearly that you had nothing to do with anything so monstrous. It is in fact a sore trial to me that any son of mine should serve this modern Moloch. But such wishes are vain, and it is, I clearly understand, your duty to do as well in such service as you have the strength and aptitude to do. In any case, it is only a kind of squeamishness, perhaps, like a man who enjoys steak and kidney (or did), but would not be connected with the butchery business. As long as war is fought with such weapons, and one accepts any profits that may accrue (such as preservation of one’s skin and even ‘victory’) it is merely shirking the issue to hold war-aircraft in special horror. I do so all the same. . . . .

This morning. . . . I saw C.S.L. for a while. His fourth (or fifth?) novel is brewing, and seems likely to clash with mine (my dimly projected third).

I have been getting a lot of new ideas about Prehistory lately (via Beowulf and other sources of which I may have written) and want to work them into the long shelved time-travel story I began. C.S.L. is planning a story about the descendants of Seth and Cain. We also begin to consider writing a book in collaboration on ‘Language’ (Nature, Origins, Functions).

Would there were time for all these projects!

93 From a letter to Christopher Tolkien

24 December 1944 (FS 70)

I am v. glad that you enjoyed the next three ch. of the Ring. The 3rd consignment shd. reach you about Dec. 10 and the last on 14 Jan. I shall be eager for more comments when you have time. Cert. Sam is the most closely drawn character, the successor to Bilbo of the first book, the genuine hobbit. Frodo is not so interesting, because he has to be highminded, and has (as it were) a vocation. The book will prob. end up with Sam. Frodo will naturally become too ennobled and rarefied by the achievement of the great Quest, and will pass West with all the great figures; but S. will settle down to the Shire and gardens and inns. C. Williams who is reading it all says the great thing is that its centre is not in strife and war and heroism (though they are understood and depicted) but in freedom, peace, ordinary life and good liking. Yet he agrees that these very things require the existence of a great world outside the Shire – lest they should grow stale by custom and turn into the humdrum. . . . .

By the way, you wrote Harebell and emended it to Hairbell. I don’t know whether it will interest you, but I looked up the whole matter of this name once – after an argument with a dogmatic scientist. It is plain (a) that the ancient name is harebell (an animal name, like so many old flower-names), and (b) that this meant the hyacinth not the campanula. Bluebell, not so old a name, was coined for the campanula, and the ‘bluebells’ of Scotland are, of course, not the hyacinths but the campanulas. The transference of the name (in England, not in Scotland, nor indeed in uncorrupted country-speech in parts of England) and its fictitious alteration hairbell seems to be due to ignorant (of etymology) and meddlesome book-botanists of recent times, of the sort that tried folk’sglove for foxglove!, by whom we’ve been led astray. As for the latter, the only part of the name that is doubtful is the glove, not the fox. Foxes glófa occurs in Anglo-Saxon but also in form -clófa: in old herbals, where it seems pretty rashly applied to plants with big broad leaves, e.g. burdock (called also foxes clife, cf. clifwyrt

=foxglove). The causes of these ancient associations with animals are little known or understood. Perhaps they sometimes depend on lost beast-fables. It would be tempting to try and make some fables to fit the names.

Are you still inventing names for the nameless flowers you meet? If so, remember that the old names are not always descriptive, but often mysterious! My best inventions (in elvish of the Gnomish dialect) were elanor and nifredil; though I like A-S symbelmynë or evermind found on the Great Mound of Rohan. I think I shall have to invent some more for Sam’s garden at the end.

94 To Christopher Tolkien

28 December 1944 (FS 71)

20 Northmoor Road, Oxford

My dearest:

You have no need to reproach yourself! We are getting lots of letters from you, and v. quickly. . . . . I am glad the third lot of Ring arrived to date, and that you liked it – although it seems to have added to yr. homesickness. It just shows the difference between life and literature: for anyone who found himself actually on the stairs of Kirith Ungol would wish to exchange it for almost any other place in the world, save Mordor itself. But if lit. teaches us anything at all, it is this: that we have in us an eternal element, free from care and fear, which can survey the things that in ‘life’ we call evil with serenity (that is not without appreciating their quality, but without any disturbance of our spiritual equilibrium). Not in the same way, but in some such way, we shall all doubtless survey our own story when we know it (and a great deal more of the Whole Story). I am afraid the next two chapters won’t come for some time (about middle of Jan) which is a pity, as not only are they (I think) v. moving and exciting, but Sam has some interesting comments on the rel. of stories and actual ‘adventures’. But I count it a triumph that these two chapters, which I did not think as good as the rest of Book IV, could distract you from the noise of the Air Crew Room!. . . .

The weather has for me been one of the chief events of Christmas. It froze hard with a heavy fog, and so we have had displays of Hoarfrost such as I only remember once in Oxford before (in the other house

I think) and only twice before in my life. One of the most lovely events of Northern Nature. We woke (late) on St Stephen’s Day to find all our windows opaque, painted over with frost-patterns, and outside a dim silent misty world, all white, but with a light jewelry of rime; every cobweb a little lace net, even the old fowls’ tent a diamond-patterned pavilion. I spent the day (after chores, that is from about 11.30, as I got up late) out of doors, well wrapped up in old rags, hewing old brambles and making a fire the smoke of which rose in a still unmoving column straight up into the fog-roof. . . . . The rime was yesterday even thicker and more fantastic. When a gleam of sun (about 11) got through it was breathtakingly beautiful: trees like motionless fountains of white branching spray against a golden light and, high overhead, a pale translucent blue. It did not melt. About 11 p.m. the fog cleared and a high round moon lit the whole scene with a deadly white light: a vision of some other world or time. It was so still that I stood in the garden hatless and uncloaked without a shiver, though there must have been many degrees of frost. . . . .

Mr Eden in the house

the other day expressed pain at the occurrences in Greece ‘the home of democracy’. Is he ignorant, or insincere? δημοχρατìα was not in Greek a word of approval but was nearly equivalent to ‘mob-rule’; and he neglected to note that Greek Philosophers – and far more is Greece the home of philosophy – did not approve of it. And the great Greek states, esp. Athens at the time of its high art and power, were rather Dictatorships, if they were not military monarchies like Sparta! And modern Greece has as little connexion with ancient Hellas as we have with Britain before Julius Agricola. . . . .

Your own Father.