По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

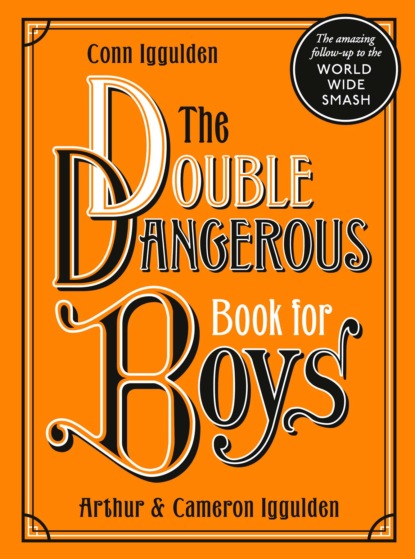

The Double Dangerous Book for Boys

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Additional contributors (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture credits (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

In this long-awaited follow-up to his much-loved bestseller, written with his sons Cameron and Arthur, Conn Iggulden presents a brand-new compendium of cunning schemes, projects, tricks, games and tales of extraordinary courage.

Whether it’s building a flying machine, learning how to pick a lock, discovering the world’s greatest speeches or mastering a Rubik’s cube, The Double Dangerous Book for Boys is the ultimate companion, to be cherished by readers and doers of all ages.

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_0a6416b1-ba6f-547f-9563-f0a3a62d66b9)

‘Boys – you are here to study, and while you are at it, study hard. When you have got the chance to play outside, play hard. Do not forget this, that in the long run the man who shirks his work will shirk his play. I remember a professor in Yale speaking to me of a member of the Yale eleven some years ago, and saying: “That fellow is going to fail. He stands too low in his studies. He is slack there, and he will be slack when it comes to the hard work on the gridiron.” He did fail.

‘You are preparing yourself for the best work of life. During your schooldays, and in after-life, I earnestly believe in each of you having as good a time as possible, but making it come second to doing the best kind of work possible. And in your studies, and in your sports in school, and afterwards in life in doing your work in the great world, it is a safe plan to follow this rule – a rule I once heard preached on the football field: Don’t flinch, don’t foul, and hit the line hard.’

THE ADVICE OF US PRESIDENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT, GIVEN TO THE READERS OF THE BOY’S OWN PAPER IN 1903

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_2257bc3c-3c6c-5379-9fad-ed1eed7e19e4)

In 2006, there didn’t seem to be many books of the kind I used to love. I wanted adventures, catapults, crystals, knowledge, history and craftsmanship. I wanted to read dozens of chapters, each different from the last. In short, I wanted a book I could hide in a treehouse – after I’d used it to build one. With my brother Harry, I worked for six months in a shed and wrote chapters on all the things that interested us – from cloud formations and astronomy, to juggling and tripwires. When it was finished, we sent it to the publishers. We didn’t set out to write a bestseller. We just wanted to celebrate the wonderful, daft ideas of boyhood – when all doors are open, the future is unwritten and summers seem to last a really long time.

Thank you to all those who recommended it to friends and family. You made the publisher reprint that red and gold hardback over and over. You gave the book to a wider audience – to sons, grandsons, nephews, brothers and fathers. We said it would appeal to ‘every boy from eight to eighty’ and that was about how it turned out. If I am remembered for just one book, if my tales of Caesar and Genghis and the Wars of the Roses are all forgotten, I don’t mind too much if someone dusts off the Dangerous Book in an attic and settles down to read with a smile.

I wrote this one with my two sons. One has become a young man since the original Dangerous Book came out. The other has reached the age of ten. He runs around like Huckleberry Finn and should wear shoes more often, probably. I thought for a while that I’d covered everything in the first book, but there’s nothing like raising boys for surprising you.

Twelve years have passed since I first roughed out a chapter on conkers for a publisher. I wrote then, ‘In this age of video games and mobile phones, there must still be a place for knots, treehouses and stories of incredible courage.’ That’s just as important today – though how we missed picking a lock, making an elastic-band gun and learning sign language, I’ll never know. In the intervening years, I wrote down a good idea whenever I heard one. Perhaps I always knew I’d go back and do another book. These are all new chapters, from casting things in resin, doing table tricks and wiring a lamp, to learning strength exercises, the twelve Caesars, stress balls and ancient ruins. There is also a design for a paper aeroplane – and, yes, it’s even better than the last one. The world is full of fascinating things. You’ll see.

Conn Iggulden

NOTES FROM THE TREEHOUSE (#ulink_ab0e5558-ceb2-5636-b065-e2a66dac6e74)

For us, this has been a chance to act like boys without consequences: to make catapults, build igloos and mix chemicals. We spent two days casting our grandfather’s beans in resin to preserve them for ever, and who knows how many evenings playing cards with our family. We learned to make a paper frog jump and to polish shoes like the British Army.

Yet it was also a chance to show our dad some of the things we knew and he didn’t. Those sunny afternoons the three of us spent learning sign language or struggling to teach him how to solve a Rubik’s cube will be some we never forget. For all that, we are very grateful.

So when we have sons of our own and we pick up this book, what will stay in our minds and our memories will not be individual triumphs and disasters.

No. In the end, what matters most is that we did these things together.

Cameron Iggulden Arthur Iggulden

PICKING LOCKS (#ulink_af76ac68-89aa-53ab-abfd-c42a5e78189b)

To open a padlock or the cylinder lock of a door without a key, you need to have an idea of how that lock works. The process of picking the lock is actually fairly simple and involves just two tools. When we were young, all the spies and heroes on TV seemed to be able to do it in five seconds with a bent hairpin. It felt a little like a superpower. The truth is that it’s a little trickier, but not that much. While researching this, we managed to open an old padlock – and that was one of the most satisfying moments of a lifetime.

Before we get to picks, look at all the illustrations in this chapter, preferably with a padlock in hand. A standard padlock is identical in function to the cylinder lock on a front door. A cylinder – usually of brass – has to turn to release the lock. It cannot turn while a number of pins pass through it, blocking it from moving. Those pins come in two parts: a driver pin and a differ pin, with a spring pressing them down and the shape of the lock holding them in place. The different lengths of the differ pins match the key to the lock.

Cylinder lock

Standard tools

Pin set-up

When the correct key is pushed in, it raises those pins, one by one, to a shear point. When the differ pins are raised to the shear point, the cylinder turns. The trick, then, is to copy the action of that key.

LOCK PICKS

Slightly to our surprise, two pieces of wire might work. However, we discovered that only after purchasing four different sets of lock picks. The cheapest was £3 and fitted inside a fake credit card. The most expensive came with two Perspex locks and about twenty different lock picks. We don’t usually recommend internet purchases. In this case, though, search for ‘lock picks’ and consider buying a Perspex lock or asking for one as a present. They’re interesting things.

Although this chapter is not intended to make you into a professional locksmith, it is our hope that, with a bit of practice, you’ll be able to open a padlock of your very own. Or your front door.

The first tool is called a tension tool or tension wrench. It keeps a slight turning force on the lock as you attempt to raise the pins. You’ll need a stiff piece of metal – an ordinary paperclip would bend too easily. Examples can be seen below. Note that they all have a sharp bend in common.

Types of tension tool

Some hooks and rakes

The idea is to insert the tension tool into the lock and maintain a constant clockwise turning pressure as you insert the lock pick. That pressure strains the pins slightly so they remain in place as you adjust them. It also means that if something goes right and the lock is freed, it turns immediately. In practice, we got used to keeping gentle pressure on – beginners usually press too hard – until it suddenly turned, sometimes quite unexpectedly.

The second tool is the actual lock pick – a hook or a rake. The rakes might look a little like a key, while a hook is designed to raise pins to the shear line one by one. That is why a stiff hairpin with a bent end can be used by a skilful locksmith.

Practise on a cheap padlock – as large as you can find, so that the pins are obvious. Begin by looking into the lock and seeing where the first pin sits.

When you are ready, insert the tension tool, moving it as far out of the way as you can. Put a little pressure in the direction the key would turn the lock. Then insert your lock pick. If it is the rake style, you’ll have to fiddle it back and forth, getting a feel for the pins within. That action can result in lifting the pins into place, so try that first – just move the pick back and forth like a key a dozen times, while keeping that gentle turning pressure on. Alternatively, if your pick has a bend at the end – the one known as a hook – you’ll want to reach right to the back and feel the ends of the pins, one by one, raising them up to the shear line.

The first time we tried this on a proper padlock, it took about two minutes. We decided there and then that we were lock-picking geniuses. Unfortunately, that overconfidence led to the lock being snapped shut again. The second attempt took well over half an hour of constant fiddling with both a hook and a rake. It was harder than we’d realised, but the wonder of it was that it worked at all. For those of you, like us, who have never understood how lock picks, or indeed cylinder locks, worked, this was a thing of awe.

In our research, we also came across the idea of a ‘bump’ key. These are keys for cylinder locks that do the job of a rake and tension tool in one go. They are inserted into a lock and either wiggled back and forth like a rake or tapped. We’ve included an example to show what they look like, but we had no luck in using ours at all. Lock picks are clearly better.

The most satisfying combination was the padlock pictured, opened with a hook and a broad wire tension wrench.

Finally – enjoy the knowledge and the skill. One day, it might even come in useful.

EXTRAORDINARY STORIES – PART ONE: ERNEST SHACKLETON (#ulink_e349fb50-dbb7-5a60-9797-22affed1c8a8)

PA/PA Archive/PA Images

‘For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.’

Raymond Priestley, part of Shackleton’s Nimrod polar expedition team as well as Scott’s Terra Nova expedition

Born in Ireland to an Anglo-Irish family on 15 February 1874, Ernest Shackleton came to England at the age of ten and was educated at Dulwich College in London, of which more later. Along with a small group of elite explorers at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, Shackleton chose to pit himself against the last truly unknown continent: Antarctica. When things went wrong, he called on depths of character and courage that still inspire today. Wherever leadership is taught around the western world, the name of Shackleton is spoken with quiet reverence.

Shackleton learned his seacraft in the Merchant Navy, joining at the age of sixteen. In 1898, aged just twenty-four, he passed as Master: a qualification to command a British ship anywhere in the world. When he was twenty-seven, he joined the 1901 Discovery expedition under Robert Falcon Scott, mapping the first part of the Antarctic continent. There, Shackleton fell ill and had to be sent to New Zealand to recover. He was bitterly disappointed.

Three years later, Shackleton returned as leader of his own Nimrod expedition – named after the ship. Shackleton and three companions made an attempt on the South Pole in horrific weather conditions. They came to within 97 miles of it, but by then they were dangerously low on food. Shackleton made the decision to turn back, though they had come closer than anyone before them. Wryly, he told his wife, ‘I thought you would prefer a live donkey to a dead lion.’ He came home a hero and was knighted by King Edward VII. However, the Pole remained unconquered – and Shackleton had caught the bug for the strange ‘white warfare’ of the south.