По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

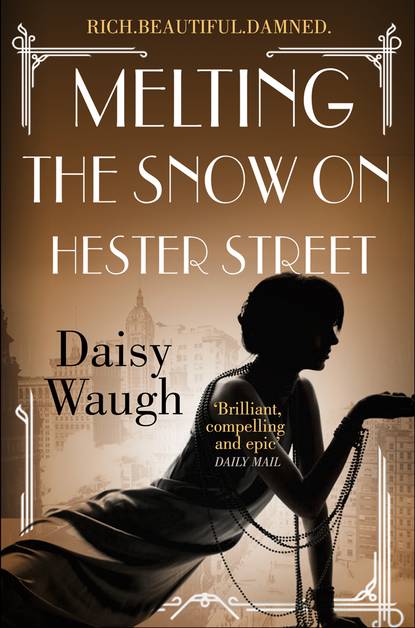

Melting the Snow on Hester Street

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Ah, Miss Beekman!’ he would sigh, above all the racket of the whirring. ‘A born machinist, if ever there was one!’ As if that were any kind of compliment. And he would turn to the rest of the row, heads bowed, necks and backs twisted over their work: ‘If only all you girls could work as efficiently as the lovely Miss Beekman!’

She corrected him once. ‘It’s Mrs Beekman, Mr Blumenkranz.’ Though, strictly speaking, it wasn’t. She was still Miss Kappelman. She and Matz weren’t yet married. It was something Eleana’s mother protested about from time to time. But somehow they had never quite got around to it. There was always something else more urgent to be done, some other more essential way to spend the time and money.

Mr Blumenkranz knew perfectly well she lived with Matz Beekman the cutter – Union sympathist and nothing but trouble, as far as Blumenkranz was concerned. If he could have his way the man would be fired. But a good cutter was hard to find. And everyone knew, Matz was the best they had. So Blumenkranz ignored Eleana’s comment. He laid a plump, yearning hand on her thin shoulder. ‘Continue your work like this, Miss Beekman,’ he said to her, ‘and before long we shall make you head of the line!’

Head of the line. Meant an extra $1 a week.

‘Head of the line, Miss Beekman! I don’t need to remind you – it’s another dollar a week!’

She let his hand rest on her shoulder – glanced across at Matz briefly, at the far end of the same floor, where the cutters stood. But Matz was oblivious – busy with his knife, slashing away, muttering Marxist revolution into the ear of the cutter beside him. She let Blumenkranz’s finger touch the skin at the top of her neck. Felt nothing – not a shiver of revulsion, because after all, the moment would pass.

When he finally wandered away, Dora, working beside Eleana, glowered at her closest friend.

‘Dershtikt zolstu vern!’ she said furiously. ‘You’re such a fool.’

‘You think so?’ Eleana giggled. ‘Why’s that? The stupid man is driving me crazy!’

‘“Miss” Beekman. “Mrs” Beekman. Who the hell cares? Not you! That’s for sure. Or you might have done something about it.’

‘Oh!’ Eleana tutted mildly. ‘For sure I care.’

‘Blumenkranz adores you, Miss Eleana Kappelman. You’re his One and Only.’

‘Nonsense! Shh!’

Dora chortled. ‘For sure – you’re his Chosen One, Ellie! The Only Girl for Him.’

‘Shut up, Dora!’

‘He loves you better than his own life!’

‘You’ll have us both fired!’

‘Carry on treating him as you do, Eleana, and pretty soon you shall be out of a job. That’s for certain.’

Eleana tipped her head to imply disagreement, but said nothing.

‘You want another a dollar a week? Or don’t you?’ her friend burst out impatiently.

‘Of course I want an extra dollar a week.’

‘Because if you don’t want it, “Mrs” Beekman, I surely do! Mr Blumenkranz can call me anything he likes! I’ll take an extra dollar for it, gladly.’

‘I’m sure you would, my friend,’ Eleana smiled.

‘You think I’m a kurve? Very well. Perhaps it’s so. I am a survivor. That’s what I am.’

‘And a kurve,’ Eleana added, laughing now. ‘And I shall tell your mama, too. The very next time I see her.’

Dora smiled. ‘You think my mama was any better in her day?’

‘Well … yes, Dora.’ Eleana looked at her, quite startled. ‘Indeed I do! And you know it too! You’re mother is a good woman.’

‘Well, Eleana, and so am I. That is exactly my point. I, too, am a good woman. And so are you. But a “good woman” needs to survive. And these are different times. This is America. Life isn’t what it was in the Old—’

‘Oh, please don’t start …’

It wasn’t that Eleana disagreed with her. Far from it. She only wished that all roads, all conversations – everything – didn’t have to lead to the same point. Dora’s socialism was becoming more irksome, more all-consuming than even Matz’s.

Nevertheless, Eleana didn’t correct Mr Blumenkranz again. She put up with his calling her Miss Beekman, leaning over her shoulder so his warm breath ran damp down her spine, and always smiled brightly when he passed. By the time of the strike neither the salary raise, nor the promised head-of-line advancement had materialized. On the other hand, she still had a job at the factory.

And here he was still, all these months later, slip-sliding after her over the ice as she returned from the Greene Street picket line. ‘Wait, Eleana!’ he panted, skidding in the frozen grime. ‘Can’t you stop a moment? I have something terribly important—’

‘I have to get home, sir,’ she said, still walking. ‘I have a small daughter waiting. Unless …’ Away from the factory floor, in these teeming streets, it was harder to hide her disdain. She threw him a glance, mid-stride. ‘Unless of course you have a message for the workers?’ She smiled at him, without warmth. ‘In which case, I’ll be sure to pass it on.’

‘Not for all the workers. No.’

‘Oh. Well then.’

‘Eleana.’ He took hold of her sleeve and pulled her to a halt. She might have snatched it back. She fought the urge. Because – even now, in the street, with the pathetic, pleading look in his eye, he was still powerful. The strike would not last forever, and there was the life beyond it to consider, when Mr Blumenkranz would once again be standing behind her, his hand on her shoulder, his finger on her neck – choosing whether to fire her, or to make her head of the line.

‘What is it, Mr Blumenkranz?’ she snapped.

He seemed surprised, as if he hadn’t really expected her to stop. ‘I have an offer for you,’ he said. ‘I wrote it down …’ He fumbled in the pockets of his thick winter coat. Eleana, standing still and wearing a jacket far thinner than his, began to shiver. ‘Wait a moment,’ he mumbled. ‘Wait there …’ But the paper could not be found, not in all the many pockets of his thick, warm coat and, finally, he abandoned the search. ‘I simply wanted to say … that you’re better than all this! It is irresponsible nonsense, what you are engaged in, and you can do better, Eleana. Much, much better.’

‘Better than what?’

‘Look at you – so cold. Your coat is so thin.’

‘Certainly it is thinner than yours.’

‘Eleana, my dear, you know you cannot win. None of you can win!’

‘Several other factories have already settled. You know they have.’

‘But not Triangle! Mr Blanck and Mr Harris have both said that they will fight you to the end. And they can because they have the rescources, and they have done so and, trust me, they will continue to do so. They will keep the factory working with or without you. They will never accept the Union. Never.’

He looked up at her, spotted the split-second of uncertainty in her eyes and, instinctively, he pressed his advantage. ‘But I could help you,’ he wheedled. ‘If you would allow me, Eleana, I could help you. Did you have breakfast this morning? I’ll bet you didn’t.’ His eyes were on her lips. ‘I can organize a payment. For you. It would be our secret, just between us. I can do that … if you are willing …’

‘What sort of payment, Mr Blumenkranz?’ she asked him politely. ‘Tell me, sir. What did you have in mind?’

But he didn’t hear her, not properly. He was gazing at her lips, and imagining himself, with his arms around her – pushing her back into the alley, right there, behind the rubble, the pile of rotting … whatever it was, and pulling up her skirt – and he couldn’t do all that and listen properly, not at the same time.

‘… Fair pay for all,’ she was saying. ‘Union recognition. Fewer hours for all of us, Mr Blumenkranz, not just for me. It cannot continue …’

‘But I can help you,’ Mr Blumenkranz pleaded. ‘You look hungry. Eleana. Of course you are hungry! What are you living off, while the strike is on? You cannot live on ideals! And nor can your child. Think of your child! Do you need money? I can give you money. How much do you need?’ Again, he was fumbling in his pockets.

But this time, when he looked up, she was gone; vanished. And he was standing alone on the bustling, noisy street. Yearning. Burning.