По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

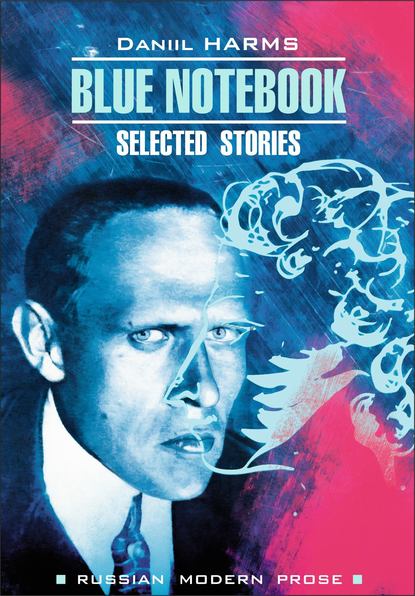

Blue Notebook / Голубая тетрадь. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Автор

Жанр

Год написания книги

2020

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Koka Briansky: Not idge, but ma – rri – age!

Mother: What do you mean, not idge?

Koka Briansky: Yes, not idge, that's all!

Mother: What?

Koka Briansky: Yes, not idge. Do you under-stand?! Not idge!

Mother: You're on about that idge again. I don't know what idge's got to do with.

Koka Briansky: Oh blow you! Ma and idge! What's up with you? Don't you realise yourself that saying just ma is senseless.

Mother: What did you say?

Koka Briansky: Ma, I said, is senseless!

Mother: Sle?

Koka Briansky: What on earth is all this! How can you possibly manage to catch only bits of words, and only the most absurd bits at that: sle! Why sle in particular?

Mother: There you go again – sle.

Koka Briansky throttles his Mother. Enter his fiancee Marusia.

On Phenomena and Existences. No. 1

The artist Michelangelo sits down on a heap of bricks and, propping his head in his hands, begins to think. Suddenly a cockerel walks past and looks at the artist Michelangelo with his round, golden eyes. Looks, but doesn't blink. At this point, the artist Michelangelo raises his head and sees the cockerel. The cockerel does not lower his gaze, doesn't blink and doesn't move his tail. The artist Michelangelo looks down and is aware of something in his eye. The artist Michelangelo rubs his eyes with his hands. And the cockerel isn't standing there any more, isn't standing there, but is walking away, walking away behind the shed, behind the shed to the poultry – run, to the poultry – run towards his hens.

And the artist Michelangelo gets up from the heap of bricks, shakes the red brick dust from his trousers, throws aside his belt and goes off to his wife.

The artist Michelangelo's wife, by the way, is extremely long, all of two rooms in length.

On the way, the artist Michelangelo meets Komarov, grasps him by the hand and shouts: – Look!…

Komarov looks and sees a sphere.

– What's that? – whispers Komarov.

And from the sky comes a roar: – It's a sphere.

– What sort of a sphere is it? – whispers Komarov.

And from the sky, the roar: – A smooth – surfaced sphere!

Komarov and the artist Michelangelo sit down on the grass and they are seated on the grass like mushrooms. They hold each other's hands and look up at the sky. And in the sky appears the outline of a huge spoon. What on earth is that? No one knows. People run about and lock themselves into their houses. They lock their doors and their windows. But will that really help? Much good it does them! It will not help.

I remember in 1884 an ordinary comet the size of a steamer appearing in the sky. It was very frightening. But now – a spoon! Some phenomenon for a comet!

Lock your windows and doors!

Can that really help? You can't barricade yourself with planks against a celestial phenomenon.

Nikolay Ivanovich Stupin lives in our house. He has a theory that everything is smoke. But in my view not everything is smoke. Maybe even there's no smoke at all. Maybe there's really nothing. There's one category only. Or maybe there's no category at all. It's hard to say.

It is said that a certain celebrated artist scrutinised a cockerel. He scrutinised it and scrutinised it and came to the conclusion that the cockerel did not exist.

The artist told his friend this, and his friend just laughed. How, he said, doesn't it exist, he said, when it's standing right here and I, he said, am clearly observing it.

And the great artist thereupon hung his head and, retaining the same posture in which he stood, sat down on a pile of bricks.

That's all.

On Phenomena and Existences. No. 2

Here's a bottle of vodka, of the lethal spirit variety. And beside it you see Nikolay Ivanovich Serpukhov.

From the bottle rise spirituous fumes. Look at the way Nikolay Ivanovich Serpukhov is breathing them in through his nose. Mark how he licks his lips and how he screws up his eyes. Evidently he is particularly partial to it and, in the main, that's because it's that lethal spirit variety.

But take note of the fact that behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back there is nothing. It's not that there isn't a cupboard there, or a chest of drawers, or at any rate some such object: but there is absolutely nothing there, not even air. Believe it or not, as you please, but behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back there is not even an airless expanse or, as they say, universal ether. To put it bluntly, there's nothing.

This is, of course, utterly inconceivable.

But we don't give a damn about that, as we are only interested in the vodka and Nikolay Ivanovich Serpukhov.

And so Nikolay Ivanovich takes the bottle of vodka in his hand and puts it to his nose. Nikolay Ivanovich sniffs it and moves his mouth like a rabbit.

Now the time has come to say that, not only behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back, but before him too – as it were, in front of his chest – and all the way round him, there is noticing. A complete absence of any kind of existence, or, as the old witticism goes, an absence of any kind of presence.

However, let us interest ourselves only in the vodka and Nikolay Ivanovich. Just imagine, Nikolay Ivanovich peers into the bottle of vodka, then he puts it to his lips, tips back the bottle bottom end up, and knocks it back – just imagine it, the whole bottle.

Nifty! Nikolay Ivanovich knocked back his vodka and looked blank. Nifty, all right! How could he!

And now this is what we have to say: as a matter of fact, not only behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back, nor merely in front and all around him, but also even inside Nikolay Ivanovich here was nothing, nothing existed.

Of course, it could all be as we have just said, and yet Nikolay Ivanovich himself could in these circumstances still be in a delightful state of existence. This is, of course, true. But, as a matter of fact, the whole thing is that Nikolay Ivanovich didn't exist and doesn't exist. That's exactly the whole thing.

You may ask: and what about the bottle of vodka? In particular, where did the vodka go, if a non – existent Nikolay Ivanovich drank it? Let's say that the bottle remained. Where, then, is the vodka? There it was and, suddenly, there it isn't. We know Nikolay Ivanovich doesn't exist, you say. So, what's the explanations?

At this stage, we ourselves become lost in conjecture.

But, anyway, what are we talking about? Surely we said that inside, as well as outside, Nikolay Ivanovich nothing exists. So if, both inside and outside, nothing exists, then that means that the bottle as well doesn't exist. Isn't that it?

But, on the other hand, take note of the following: if we are saying that nothing exists either inside or outside, then the question arises: inside and outside of what? Something evidently, all the same, does exist?

Or perhaps doesn't exist. In which case, why do we keep saying «inside» and «outside»?

No, here we have patently reached an impasse. And we ourselves don't know what to say.

Mother: What do you mean, not idge?

Koka Briansky: Yes, not idge, that's all!

Mother: What?

Koka Briansky: Yes, not idge. Do you under-stand?! Not idge!

Mother: You're on about that idge again. I don't know what idge's got to do with.

Koka Briansky: Oh blow you! Ma and idge! What's up with you? Don't you realise yourself that saying just ma is senseless.

Mother: What did you say?

Koka Briansky: Ma, I said, is senseless!

Mother: Sle?

Koka Briansky: What on earth is all this! How can you possibly manage to catch only bits of words, and only the most absurd bits at that: sle! Why sle in particular?

Mother: There you go again – sle.

Koka Briansky throttles his Mother. Enter his fiancee Marusia.

On Phenomena and Existences. No. 1

The artist Michelangelo sits down on a heap of bricks and, propping his head in his hands, begins to think. Suddenly a cockerel walks past and looks at the artist Michelangelo with his round, golden eyes. Looks, but doesn't blink. At this point, the artist Michelangelo raises his head and sees the cockerel. The cockerel does not lower his gaze, doesn't blink and doesn't move his tail. The artist Michelangelo looks down and is aware of something in his eye. The artist Michelangelo rubs his eyes with his hands. And the cockerel isn't standing there any more, isn't standing there, but is walking away, walking away behind the shed, behind the shed to the poultry – run, to the poultry – run towards his hens.

And the artist Michelangelo gets up from the heap of bricks, shakes the red brick dust from his trousers, throws aside his belt and goes off to his wife.

The artist Michelangelo's wife, by the way, is extremely long, all of two rooms in length.

On the way, the artist Michelangelo meets Komarov, grasps him by the hand and shouts: – Look!…

Komarov looks and sees a sphere.

– What's that? – whispers Komarov.

And from the sky comes a roar: – It's a sphere.

– What sort of a sphere is it? – whispers Komarov.

And from the sky, the roar: – A smooth – surfaced sphere!

Komarov and the artist Michelangelo sit down on the grass and they are seated on the grass like mushrooms. They hold each other's hands and look up at the sky. And in the sky appears the outline of a huge spoon. What on earth is that? No one knows. People run about and lock themselves into their houses. They lock their doors and their windows. But will that really help? Much good it does them! It will not help.

I remember in 1884 an ordinary comet the size of a steamer appearing in the sky. It was very frightening. But now – a spoon! Some phenomenon for a comet!

Lock your windows and doors!

Can that really help? You can't barricade yourself with planks against a celestial phenomenon.

Nikolay Ivanovich Stupin lives in our house. He has a theory that everything is smoke. But in my view not everything is smoke. Maybe even there's no smoke at all. Maybe there's really nothing. There's one category only. Or maybe there's no category at all. It's hard to say.

It is said that a certain celebrated artist scrutinised a cockerel. He scrutinised it and scrutinised it and came to the conclusion that the cockerel did not exist.

The artist told his friend this, and his friend just laughed. How, he said, doesn't it exist, he said, when it's standing right here and I, he said, am clearly observing it.

And the great artist thereupon hung his head and, retaining the same posture in which he stood, sat down on a pile of bricks.

That's all.

On Phenomena and Existences. No. 2

Here's a bottle of vodka, of the lethal spirit variety. And beside it you see Nikolay Ivanovich Serpukhov.

From the bottle rise spirituous fumes. Look at the way Nikolay Ivanovich Serpukhov is breathing them in through his nose. Mark how he licks his lips and how he screws up his eyes. Evidently he is particularly partial to it and, in the main, that's because it's that lethal spirit variety.

But take note of the fact that behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back there is nothing. It's not that there isn't a cupboard there, or a chest of drawers, or at any rate some such object: but there is absolutely nothing there, not even air. Believe it or not, as you please, but behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back there is not even an airless expanse or, as they say, universal ether. To put it bluntly, there's nothing.

This is, of course, utterly inconceivable.

But we don't give a damn about that, as we are only interested in the vodka and Nikolay Ivanovich Serpukhov.

And so Nikolay Ivanovich takes the bottle of vodka in his hand and puts it to his nose. Nikolay Ivanovich sniffs it and moves his mouth like a rabbit.

Now the time has come to say that, not only behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back, but before him too – as it were, in front of his chest – and all the way round him, there is noticing. A complete absence of any kind of existence, or, as the old witticism goes, an absence of any kind of presence.

However, let us interest ourselves only in the vodka and Nikolay Ivanovich. Just imagine, Nikolay Ivanovich peers into the bottle of vodka, then he puts it to his lips, tips back the bottle bottom end up, and knocks it back – just imagine it, the whole bottle.

Nifty! Nikolay Ivanovich knocked back his vodka and looked blank. Nifty, all right! How could he!

And now this is what we have to say: as a matter of fact, not only behind Nikolay Ivanovich's back, nor merely in front and all around him, but also even inside Nikolay Ivanovich here was nothing, nothing existed.

Of course, it could all be as we have just said, and yet Nikolay Ivanovich himself could in these circumstances still be in a delightful state of existence. This is, of course, true. But, as a matter of fact, the whole thing is that Nikolay Ivanovich didn't exist and doesn't exist. That's exactly the whole thing.

You may ask: and what about the bottle of vodka? In particular, where did the vodka go, if a non – existent Nikolay Ivanovich drank it? Let's say that the bottle remained. Where, then, is the vodka? There it was and, suddenly, there it isn't. We know Nikolay Ivanovich doesn't exist, you say. So, what's the explanations?

At this stage, we ourselves become lost in conjecture.

But, anyway, what are we talking about? Surely we said that inside, as well as outside, Nikolay Ivanovich nothing exists. So if, both inside and outside, nothing exists, then that means that the bottle as well doesn't exist. Isn't that it?

But, on the other hand, take note of the following: if we are saying that nothing exists either inside or outside, then the question arises: inside and outside of what? Something evidently, all the same, does exist?

Or perhaps doesn't exist. In which case, why do we keep saying «inside» and «outside»?

No, here we have patently reached an impasse. And we ourselves don't know what to say.