По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

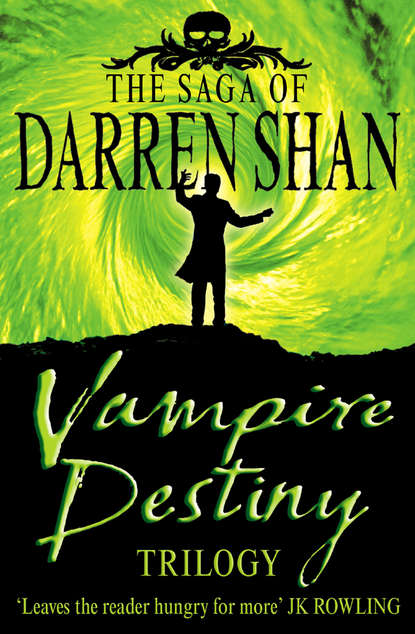

Vampire Destiny Trilogy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Indeed,” Evanna smirked. “That’s why we are going to tie the planks tightly with topes.” The squat witch began unwrapping the ropes she kept knotted around her body.

“Do you want us to look away?” I asked.

“No need,” she laughed. “I don’t plan to strip myself bare!”

The witch reeled off an incredibly long line of rope, dozens of metres in length, yet the ropes around her body didn’t diminish, and she was as discreetly covered when she stopped as she’d been at the outset. “There!” she grunted. “That should suffice.”

We spent the rest of the day constructing the raft, Evanna acting as the designer, performing magical shortcuts when our backs were turned, making our job a lot quicker and easier than it should have been. It wasn’t a large raft when finished, two and a half metres long by two wide, but we could both fit on it and lie down in comfort. Evanna wouldn’t tell us how wide the lake was, but said we’d have to sail due south and sleep on the raft a few nights at least. The raft floated nicely when we tested it and although we had no sails, we fashioned oars out of leftover planks.

“You should be fine now,” Evanna said. “You won’t be able to light a fire, but fish swim close to the surface of the lake. Catch and eat them raw. And the water is unpleasant but safe to drink.”

“Evanna …” I began, then coughed with embarrassment.

“What is it, Darren?” the witch asked.

“The gelatinous globes,” I muttered. “Will you tell us what they’re for?”

“No,” she said. “And that’s not what you wanted to ask. Out with it, please. What’s bothering you?”

“Blood,” I sighed. “It’s been ages since I last drank human blood. I’m feeling the side effects—I’ve lost a lot of my sharpness and strength. If I carry on like this, I’ll die. I was wondering if I could drink from you?”

Evanna smiled regretfully. “I would gladly let you drink from me, but I’m not human and my blood’s not fit for consumption—you’d feel a lot worse afterwards! But don’t worry. If the fates are kind, you’ll find a feeding source shortly. If they’re not,” she added darkly, “you’ll have greater problems to worry about.

“Now,” the witch said, stepping away from the raft, “I must leave you. The sooner you set off, the sooner you’ll arrive at the other side. I’ve just this to say – I’ve saved it until now because I had to – and then I’ll depart. I can’t tell you what the future has in store, but I can offer this advice—to fish in the Lake of Souls, you must borrow a net which has been used to trawl for the dead. And to access the Lake, you’ll need the holy liquid from the Temple of the Grotesque.”

“Temple of the Grotesque?” Harkat and I immediately asked together.

“Sorry,” Evanna grunted. “I can tell you that much, but nothing else.” Waving to us, the witch said, “Luck, Darren Shan. Luck, Harkat Mulds.” And then, before we could reply, she darted away, moving with magical speed, disappearing out of sight within seconds into the gloom of the coming night.

Harkat and I stared at one another silently, then turned and manoeuvred our meagre stash of possessions on to the raft. We divided the gelatinous globes into three piles: one for Harkat, one for me and one in a scrap of cloth tied to the raft, then set off in the gathering darkness across the cold, still water of the nameless lake.

CHAPTER TWELVE (#ulink_35d14a8e-c73a-5da1-b6c2-503830138b6b)

WE ROWED for most of the night, in what we hoped was a straight line (there seemed to be no currents to drag us off course), rested for a few hours either side of dawn, then began rowing again, this time navigating south by the position of the sun. By the third day we were bored out of our skulls. There was nothing to do on the calm, open lake, and no change in scenery—dark blue underneath, mostly unbroken grey overhead. Fishing distracted us for short periods each day, but the fish were plentiful and easy to catch, and soon it was back to the rowing and resting.

To keep ourselves amused, we invented games using the teeth Harkat had pulled from the dead panther. There weren’t many word games we could play with such a small complement of letters, but by giving each letter a number, we were able to pretend the teeth were dice and indulge in simple gambling games. We didn’t have anything of value to bet, so we used the bones of the fish we caught as gambling chips, and made believe they were worth vast amounts of money.

During a rest period, as Harkat was cleaning the teeth – taking his time, to stretch the job out – he picked up a long incisor, the one marked by a K, and frowned. “This is hollow,” he said, holding it up and peering through it. Putting it to his wide mouth, he blew through it, held it up again, then passed it to me.

I studied the tooth against the grey light of the sky, squinting to see better. “It’s very smooth,” I noted. “And it goes from being wide at the top to narrow at the tip.”

“It’s almost as though … a hole has been bored through it,” Harkat said.

“How, and what for?” I asked.

“Don’t know,” Harkat said. “But it’s the only one … like that.”

“Maybe an insect did it,” I suggested. “A parasite which burrows into an animal’s teeth and gnaws its way upwards, feeding on the material inside.”

Harkat stared at me for a moment, then opened his mouth as wide as he could and gurgled, “Check my teeth quick!”

“Mine first!” I yelped, anxiously probing my teeth with my tongue.

“Your teeth are tougher … than mine,” he said. “I’m more vulnerable.”

Since that was true, I leant forward to examine Harkat’s sharp grey teeth. I studied them thoroughly, but there was no sign that any had been invaded. Harkat checked mine next, but I drew a clean bill of health too. We relaxed after that – though we did a lot of prodding and jabbing with our tongues over the next few hours! – and Harkat returned to cleaning the teeth, keeping the tooth with the hole to one side, slightly away from the others.

That fourth night, as we slept after many hours of rowing, huddled together in the middle of the raft, we were woken by a thunderous flapping sound overhead. We bolted out of our sleep and sat up straight, covering our ears to drown out the noise. The sound was like nothing I’d heard before, impossibly heavy, as though a giant was beating clean his bed sheets. It was accompanied by strong, cool gusts of wind which set the water rippling and our raft rocking. It was a dark night with no break in the clouds, and we couldn’t see what was making the noise.

“What is it?” I whispered. Harkat couldn’t hear my whisper over the noise, so I repeated myself, but not too loudly, for fear of giving our position away to whatever was above.

“No idea,” Harkat replied, “but there’s something … familiar about it. I’ve heard it before … but I can’t remember where.”

The flapping sounds died away as whatever it was moved on, the water calmed and our raft steadied, leaving us shaken but unharmed. When we discussed it later, we reasoned it must have been some huge breed of bird. But in my gut, I sensed that wasn’t the answer, and by Harkat’s troubled expression and inability to fall back asleep, I was sure he sensed it too.

We rowed quicker than usual in the morning, saying little about the sounds we’d heard the night before, but gazing up often at the sky. Neither of us could explain why the noise had so alarmed us—we just felt that we’d be in big trouble if the creature came again, by the light of day.

We spent so much time staring up at the clouds that it wasn’t until early afternoon, during a brief rest period, that we looked ahead and realized we were within sight of land. “How far do you think … it is?” Harkat asked.

“I’m not sure,” I answered. “Four or five kilometres?” The land was low-lying, but there were mountains further on, tall grey peaks which blended with the clouds, which was why we hadn’t noticed them before.

“We can be there soon if we … row hard,” Harkat noted.

“So let’s row,” I grunted, and we set to our task with renewed vigour. Harkat was able to row faster than me – my strength was failing rapidly as a result of not having any human blood to drink – but I stuck my head down and pushed my muscles to their full capacity. We were both eager to make the safety of land, where at least we could find a bush to hide under if we were attacked.

We’d covered about half the distance when the air overhead reverberated with the same heavy flapping sounds that had interrupted our slumber. Gusts of wind cut up the water around us. Pausing, we looked up and spotted something hovering far above. It seemed small, but that was because it was a long way up.

“What the hell is it?” I gasped.

Harkat shook his head in answer. “It must be immense,” he muttered, “for its wings to create … this much disturbance from that high up.”

“Do you think it’s spotted us?” I asked.

“It wouldn’t be hovering there otherwise,” Harkat said.

The flapping sound and accompanying wind stopped and the figure swooped towards us with frightening speed, becoming larger by the second. I thought it meant to torpedo us, but it pulled out of its dive ten or so metres above the raft. Slowing its descent, it unfurled gigantic wings and flapped to keep itself steady. The sound was ear shattering.

“Is that … what I … think it is?” I roared, clinging to the raft as waves broke over us, eyes bulging out of my head, unable to believe that this monster was real. I wished with all my heart that Harkat would tell me I was hallucinating.

“Yes!” Harkat shouted, shattering my wishes. “I knew I … recognized it!” The Little Person crawled to the edge of the raft to gaze at the magnificent but terrifying creature of myth. He was petrified, like me, but there was also an excited gleam in his green eyes. “I’ve seen it before … in my nightmares,” he croaked, his voice only barely audible over the flapping of the extended wings. “It’s a dragon!”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#ulink_745060aa-2148-5ce0-b17b-1ae51a27bd26)

I’D NEVER in my life seen anything as wondrous as this dragon, and even though I was struck numb with fear, I found myself admiring it, unable to react to the threat it posed. Though it was impossible to accurately judge its measurements, its wingspan had to be twenty metres. The wings were a patchy light green colour, thick where they connected to its body, but thin at the tips.

The dragon’s body was seven or eight metres from snout to the tip of its tail. It put me in mind of a snake’s tapered body – it was scaled – though it had a round bulging chest which angled back towards the tail. Its scales were a dull red and gold colour underneath. From what I could see of the dragon’s back, it was dark green on top, with red flecks. It had a pair of long forelegs, ending in sharp claws, and two shorter limbs about a quarter of the way from the end of its body.

Its head was more like an alligator’s than a snake’s, long and flat, with two yellow eyes protruding from its crown, large nostrils, and a flexible lower jaw which looked like it could open wide to consume large animals. Its face was a dark purple colour and its ears were surprisingly small, pointed and set close to its eyes. It had no teeth that I could see, but the gums of its jaws looked hard and sharp. It had a long, forked tongue which flicked lazily between its lips as it hung in the air and gazed upon us.