По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

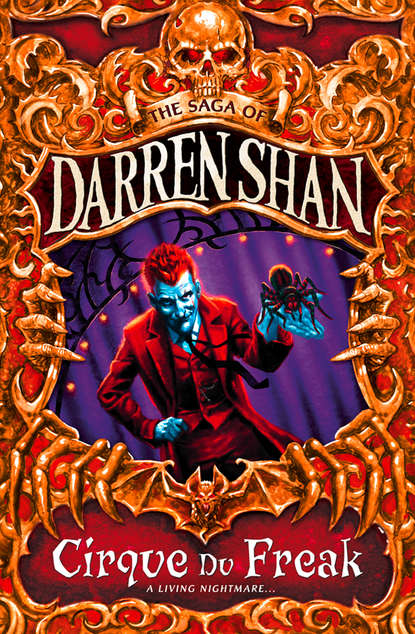

Cirque Du Freak

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Sir, it’s mine,” he said.

“Yours?” Mr Dalton blinked slowly.

“I found it near the bus stop, sir,” Steve said. “Some old guy threw it away. I thought it looked interesting, so I picked it up. I was going to ask you about it later, at the end of class.”

“Oh.” Mr Dalton tried not to look flattered but I could tell he was. “That’s different. Nothing wrong with an inquisitive mind. Sit down, Steve.” Steve sat. Mr Dalton stuck a bit of BluTack on the flyer and pinned it to the blackboard.

“Long ago,” he said, tapping the flyer, “there used to be real freak shows. Greedy con men crammed malformed people in cages and—”

“Sir, what’s malformed mean?” somebody asked.

“Someone who doesn’t look ordinary,” Mr Dalton said. “A person with three arms or two noses; somebody with no legs; somebody very short or very tall. The con men put these poor people – who were no different to you or me, except in looks – on display and called them freaks. They charged the public to stare at them, and invited them to laugh and tease. They treated the so-called “freaks” like animals. Paid them little, beat them, dressed them in rags, never allowed them to wash.”

“That’s cruel, sir,” Delaina Price – a girl near the front – said.

“Yes,” he agreed. “Freak shows were cruel, monstrous creations. That’s why I got angry when I saw this.” He tore down the flyer. “They were banned years ago, but every so often you’ll hear a rumour that they’re still going strong.”

“Do you think the Cirque Du Freak is a real freak show?” I asked.

Mr Dalton studied the flyer again, then shook his head. “I doubt it,” he said. “Probably just a cruel hoax. Still,” he added, “if it was real, I hope nobody here would dream of going.”

“Oh, no, sir,” we all said quickly.

“Because freak shows were terrible,” he said. “They pretended to be like proper circuses but they were cesspits of evil. Anybody who went to one would be just as bad as the people running it.”

“You’d have to be really twisted to want to go to one of those, sir,” Steve agreed. And then he looked at me, winked, and mouthed the words: “We’re going!”

CHAPTER THREE

STEVE PERSUADED Mr Dalton to let him keep the flyer. He said he wanted it for his bedroom wall. Mr Dalton wasn’t going to give it to him but then changed his mind. He cut off the address at the bottom before handing it over.

After school, the four of us – me, Steve, Alan Morris and Tommy Jones – gathered in the yard and studied the glossy flyer.

“It’s got to be a fake,” I said.

“Why?” Alan asked.

“They don’t allow freak shows any more,” I told him. “Wolf-men and snake-boys were outlawed years ago. Mr Dalton said so.”

“It’s not a fake!” Alan insisted.

“Where’d you get it?” Tommy asked.

“I stole it,” Alan said softly. “It belongs to my big brother.” Alan’s big brother was Tony Morris, who used to be the school’s biggest bully until he got thrown out. He’s huge and mean and ugly.

“You stole from Tony?!?” I gasped. “Have you got a death wish?”

“He won’t know it was me,” Alan said. “He had it in a pair of trousers that Mum threw in the washing machine. I stuck a blank piece of paper in when I took this out. He’ll think the ink got washed off.”

“Smart,” Steve nodded.

“Where did Tony get it?” I asked.

“There was a guy passing them out in an alley,” Alan said. “One of the circus performers, a Mr Crepsley.”

“The one with the spider?” Tommy asked.

“Yeah,” Alan answered, “only he didn’t have the spider with him. It was night and Tony was on his way back from the pub.” Tony’s not old enough to get served in a pub, but hangs around with older guys who buy drinks for him. “Mr Crepsley handed the paper to Tony and told him they’re a travelling freak show who put on secret performances in towns and cities across the world. He said you had to have a flyer to buy tickets and they only give them to people they trust. You’re not supposed to tell anyone else about the show. I only found out because Tony was in high spirits – the way he gets when he drinks – and couldn’t keep his mouth shut.”

“How much are the tickets?” Steve asked.

“Fifteen pounds each,” Alan said.

“Fifteen pounds!” we all shouted.

“Nobody’s going to pay fifteen pounds to see a bunch of freaks!” Steve snorted.

“I would,” I said.

“Me too,” Tommy agreed.

“And me,” Alan added.

“Sure,” Steve said, “but we don’t have fifteen pounds to throw away. So it’s academic, isn’t it?”

“What does academic mean?” Alan asked.

“It means we can’t afford the tickets, so it doesn’t matter if we would buy them or not,” Steve explained. “It’s easy to say you would buy something if you know you can’t.”

“How much do we have?” Alan asked.

“Tuppence ha’penny,” I laughed. It was something my dad often said.

“I’d love to go,” Tommy said sadly. “It sounds great.” He studied the picture again.

“Mr Dalton didn’t think too much of it,” Alan said.

“That’s what I mean,” Tommy said. “If Sir doesn’t like it, it must be super. Anything that adults hate is normally brilliant.”

“Are we sure we don’t have enough?” I asked. “Maybe they have discounts for children.”

“I don’t think children are allowed in,” Alan said, but he told me how much he had anyway. “Five pounds seventy.”

“I’ve got twelve pounds exactly,” Steve said.

“I have six pounds eighty-five pence,” Tommy said.

“And I have eight pounds twenty-five,” I told them. “That’s more than thirty pounds in all,” I said, adding it up in my head. “We get our pocket money tomorrow. If we pool our—”