По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

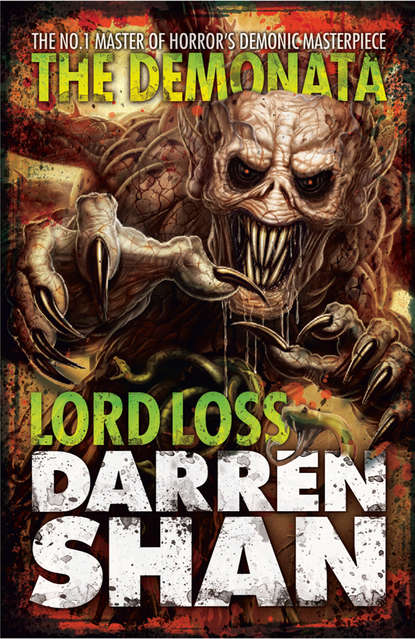

Lord Loss

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

DERVISH

→ Lost, spiralling time. Muddled happenings. Flitting in and out of reality. Momentarily here, then gone, reclaimed by madness and demons.

→ Clarity. A warm room. Police officers. I’m wrapped in blankets. A man with a kind face offers me a mug of hot chocolate. I take it. He’s asking questions. His words sail over and through me. Staring into the dark liquid of the mug, I begin to fade out of reality. To avoid the return to nightmares, I lift my head and focus on his moving lips.

For a long time — nothing. Then whispers. They grow. Like turning up the volume on the TV. Not all his words make sense — there’s a roaring sound inside my head — but I get his general drift. He’s asking about the murders.

“Demons,” I mutter, my first utterance since my soul-wrenching cry.

His face lights up and he snaps forward. More questions. Quicker than before. Louder. More urgent. Amidst the babble, I hear him ask, “Did you see them?”

“Yes,” I croak. “Demons.”

He frowns. Asks something else. I tune out. The world flames at the edges. A ball of madness condenses around me, trapping me, devouring me, cutting off all but the nightmares.

→ A different room. Different officers. More demanding than the last one. Not as gentle. Asking questions loudly, facing me directly, holding my head up until our eyes meet and they have my attention. One holds up a photograph — red, a body torn down the middle.

“Gret,” I moan.

“I know it’s hard,” an officer says, sympathy mixed with impatience, “but did you see who killed her?”

“Demons,” I sigh.

“Demons don’t exist, Grubbs,” the officer growls. “You’re old enough to know that. Look, I know it’s hard,” he repeats himself, “but you have to focus. You have to help us find the people who did this.”

“You’re our only witness, Grubbs,” his colleague murmurs. “You saw them. Nobody else did. We know you don’t want to think about it right now, but you have to. For your parents. For Gret.”

The other cop waves the photo in my face again. “Give us something — anything!” he pleads. “How many were there? Did you see their faces or were they wearing masks? How much of it did you witness? Can you…”

Fading. Bye-bye officers. Hello horror.

→ Screaming. Deafening cries. Looking around, wondering who’s making such a racket and why they aren’t being silenced. Then I realise it’s me screaming.

In a white room. Hands bound by a tight white jacket. I’ve never seen a real one before, but I know what it is — a straitjacket.

I focus on making the screams stop and they slowly die away to a whimper. I don’t know how long I’ve been roaring, but my throat’s dry and painful, as though I’ve been testing its limits for weeks without pause.

There’s a hard plastic mug set in a holder on a small table to my left. A straw sticks out of it. I ease my lips around the head of the straw and swallow. Flat Coke. It hurts going down, but after a couple of mouthfuls it’s wonderful.

Refreshed, I study my cell. Padded walls. Dim lights. A steel door with a strong plastic panel in the upper half, instead of glass.

I stumble to the panel and stare out. Can’t see much — the area beyond is dark, so the plastic’s mostly reflective. I study my face in the makeshift mirror. My eyes aren’t my own — bloodshot, wild, rimmed with black circles. Lips bitten to tatters. Scratches on my face — self-inflicted. Hair cut short, tighter than I’d like. A large purple bruise on my forehead.

A face pops up close on the other side of the glass. I fall backwards with fright. The door opens and a large, smiling woman enters. “It’s OK,” she says softly. “My name’s Leah. I’ve been looking after you.”

“Wh-wh… where am I?” I gasp.

“Some place safe,” she replies. She bends and touches the bruise on my forehead with two soft, gentle fingers. “You’ve been through hell, but you’re OK now. It’s all uphill from here. Now that you’ve snapped out of your delirium, we can work on…”

I lose track of what Leah’s saying. Behind her, in the doorway, I imagine a pair of demons — Vein and Artery. The sane part of me knows they aren’t real, just visions, but that part of me has no control over my senses any more. Backing up against one of the padded walls, I stare blankly at the make-believe demons as they dance around my cell, making crude gestures and mimed threats.

Leah goes on talking. The imaginary Vein and Artery go on dancing. I slip back into the shell of my nightmares — almost gratefully.

→ In and out. Quiet moments of reality. Sudden flashes of insanity and terror.

I’m being held in an institute for people with problems — that’s all any of my nurses will tell me. No names. No mingling with the other patients. White rooms. Nurses — Leah, Kelly, Tim, Aleta, Emilia and others, all nice, all concerned, all unable to coax me back from my nightmares when they strike. Doctors with names which I don’t bother memorising. They examine me at regular intervals. Make notes. Ask questions.

→ What did you see?

→ What did the killers look like?

→ Why do you insist on calling them demons?

→ You know demons aren’t real. Who are the real killers?

One of them asks if I committed the murders. She’s a grey-haired, sharp-eyed woman. Not as kindly as the rest. The ‘bad doctor’ to their ‘good doctors’. She presses me harder as the days slip by. Challenges me. Shows me photos which make me cry.

I start calling her Doctor Slaughter, but only to myself, not out loud. When she comes with her questions and cold eyes, I open myself to the nightmares — always hovering on the edges, eager to embrace me — and lose myself to the real world. After a few of these intentional fade-outs, they obviously decide to abandon the shock tactics and that’s the last I see of Doctor Slaughter.

→ Time dragging or disappearing into nightmares. No ordinary time. No lazy afternoons or quiet mornings. The murders impossible to forget. Grief and fear tainting my every waking and sleeping moment.

Routines are important, according to my doctors and nurses, who wish to put a stop to my nightmarish withdrawals. They’re trying to get me back to real time. They surround me with clocks. Make me wear two watches. Stress the times at which I’m to eat and bathe, exercise and sleep.

Lots of pills and injections. Leah says it’s only temporary, to calm me down. Says they don’t like dosing patients here. They prefer to talk us through our problems, not make us forget them.

The drugs numb me to the nightmares, but also to everything else. Impossible to feel interest or boredom, excitement or despair. I wander around the hospital – I have a free run now that I’m no longer violent — in a daze, zombiefied, staring at clock faces, counting the seconds until my next pill.

→ Off the pills. Coming down hard. Screaming fits. Fighting the nurses. Craving numbness. Needing pills!

They ignore my screams and pleas. Leah explains what’s happening. I’m on a long-term treatment plan. The drugs put a stop to the nightmares and anchored me in the real world — step one. Now I have to learn to function in it as a normal person, free of medicinal depressants — step two.

I try explaining my situation to her — my nightmares won’t ever go away, because the demons I saw were real – but she refuses to listen. Nobody believes me when I talk about the demons. They accept that I was in the house at the time of the murders, and that I witnessed something dreadful, but they can’t see beyond human horrors. They think I imagined the demons to mask the truth. One doctor says it’s easier to believe in demons than evil humans. Says a wicked person is far scarier than a fanciful demon.

Moron! He wouldn’t say that if he’d seen the crocodile-headed Vein or the cockroach-crowned Artery!

→ Gradual improvement. I lose my craving for drugs and no longer throw fits. But I don’t progress as quickly as my doctors anticipated. I keep slipping back into the world of nightmares, losing my grip on reality. I don’t talk openly with my nurses and doctors. I don’t discuss my fears and pains. Sometimes I babble incoherently and can’t interpret the words of those around me. Or I’ll stand staring at a tree or bush through one of the institute windows all day long, or not get up in the morning, despite the best rousing efforts of my nurses. I’m fighting them. They don’t believe my story, so they can’t truly understand me, so they can’t really help me. So I fight them. Out of fear and spite.

→ Somewhere in the middle of the confusion, relatives arrive. The doctors want me to focus on the world outside this institute. They think the way to do that is to reintroduce me to my family, break down my sense of overwhelming isolation. I think the plan is for the visitors to fuss over me, so that I want to be with them, so I’ll then play ball with the doctors when they start in with the questions.

Aunt Kate’s the first. She clutches me tight and weeps. Talks about Mum, Dad and Gret non-stop, recalling all the good times that she can remember. Begs me to let the doctors help me, to talk with them, so I can get better and go home and live with her. I say nothing, just stare off into space and think about Dad hanging upside-down. Aunt Kate leaves less than an hour later, still sobbing.

More relatives drop in during the following days and weeks, rounded up by the doctors. Aunts, uncles, cousins — both sides of the family tree. Some are old acquaintances. Some I’ve never seen before. I don’t respond to any of them. I can tell they’re just like the doctors. They don’t believe me.

Lots of questions from my carers. Why don’t I talk to my relatives? Do I like them? Are there others I prefer? Am I afraid of people? How would I feel about leaving here and staying with one of the well-wishers for a while?

They’re trying to ship me out. It’s not that they’re sick of me — just step three on my path to recovery. Since I won’t rally to their calls in here, they hope that a taste of the real world will make me more receptive. (I haven’t developed any great insights into the human way of thinking — I know all this because Leah and the other nurses tell me. They say it’s good for me to know what they’re thinking, what their plans are.)

I do my best to give them what they want – I’d love if they could cure me — but it’s difficult. The relatives remind me of what happened. They can’t act naturally around me. They look at me with pitying — sometimes fearful — expressions. But I try. I listen. I respond.