По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

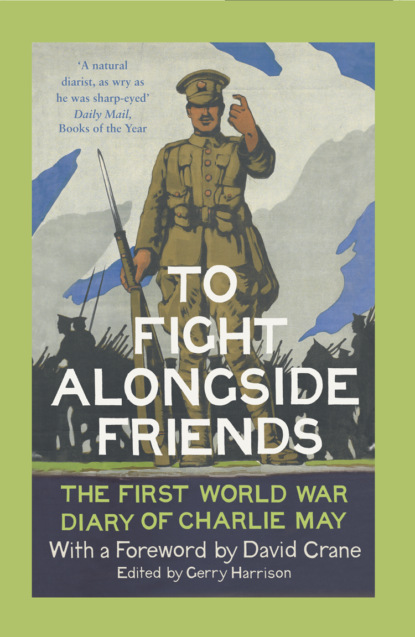

To Fight Alongside Friends: The First World War Diaries of Charlie May

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter 11: ‘The greatest battle in the world is on the eve of breaking’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: ‘We are all agog with expectancy’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: ‘My dear one could not have died more honourably or gloriously …’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Writings (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index of Names (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations (#ulink_39fc8dee-5927-5061-a990-d9943b4c43ea)

Frontispiece

1 (#ulink_771c9b49-e973-5b35-8853-f33b809d943c). Portrait of Captain Charlie May (Photo courtesy of family)

Plates

2 (#litres_trial_promo). Charles Edward May (Photo courtesy of Jason Bauchop)

3 (#litres_trial_promo). The steamship Westmeath (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

4 (#litres_trial_promo). Port Chalmers, Dunedin, 1880 (Photo courtesy of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ref: O.24194)

5 (#litres_trial_promo). Princes Street, Dunedin, 1885 (Photo courtesy of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ref: C.011756)

6 (#litres_trial_promo). The May-Oatway Fire Alarm (Photo courtesy of Dunedin Fire Brigade Restoration Society Inc.)

7 (#litres_trial_promo). The May Family in London, about 1905 (Photo courtesy of Susan and Charles Worledge)

8 (#litres_trial_promo). Lily May’s wedding, 1909 (Photo courtesy Susan and Charles Worledge)

9 (#litres_trial_promo). Trooper May at camp, King Edward’s Horse (Photo courtesy of family)

10 (#litres_trial_promo). Charlie outside tent, Salisbury Plain (Photo courtesy of family)

11 (#litres_trial_promo). Private Richard Tawney (Photo courtesy of LSE, Ref: LSE/Tawney/27/11)

12 (#litres_trial_promo). Captain Alfred Bland (Photograph courtesy of Daniel Mace)

13 (#litres_trial_promo). Lieut. William Gomersall (Photograph courtesy of Victor Gomersall)

14 (#litres_trial_promo). Private Arthur Bunting (Photograph courtesy Adrian Bunting)

15 (#litres_trial_promo). Maude with Pauline in her christening robe, 1914 (Photo courtesy of family)

16 (#litres_trial_promo). Maude and Pauline in leather-bound case(Photo courtesy of Regimental Archives, Ref: MR4/17/295/4/4)

17 (#litres_trial_promo). Maude, Pauline and Charlie, perhaps on leave, Feb. 1915 (Photo courtesy of family)

18 (#litres_trial_promo). Maude (Photo courtesy of the Regimental Archives, Ref: MR4/17/295/4/4)

19 (#litres_trial_promo). Pauline, aged about four with Teddy bear, c.1918 (Photo courtesy of the Regimental Archives, Ref: MR4/17/295/4/4)

20 (#litres_trial_promo). Charlie’s personal diaries (Photo courtesy of the Regimental Archives, Refs: MR4/17/295/1/1-7)

21 (#litres_trial_promo). Pencil sketch by Charlie, ‘Our Camp in the Bois’ (Photo courtesy of the Regimental Archives, Ref: MR4/17/295/5/1)

22 (#litres_trial_promo). Charles Edward May, seated, at Imperial School of Instruction camp, Zeitoun, Egypt, 1915 (Photo courtesy of Susan and Charles Worledge)

23 (#litres_trial_promo). Dantzig Alley British Cemetery (Photograph courtesy of Derek Taylor)

24 (#litres_trial_promo). Charlie’s headstone, Dantzig Alley (Photograph courtesy of Derek Taylor)

25 (#litres_trial_promo). Frank Earles, early1920s (Photograph courtesy of Rosie Gutteridge)

26 (#litres_trial_promo). Pauline, a friend and Maude in Fontainebleau, France, 1922 (Photo courtesy of family)

27 (#litres_trial_promo). Pauline’s wedding to Harry Karet, 1950(Photo courtesy of family)

Foreword (#ulink_1626d15e-0138-5aea-9f55-503948a963b3)

What is it that makes one diary live and another simply die on the page? Nine times out of ten it is down to the intrinsic interest of the material or the quality of the writing; but every so often one comes across a diary where it is the sense of personality behind it that lifts it out of the ordinary: such a diary is that of Captain Charlie May, killed in the early morning of 1 July 1916, leading his men of B Company of the 22nd Manchester Service Battalion into action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

There is nothing very remarkable about Charles May, and that is the point about him: from the first page of his diary to the last haunting entries he feels so utterly familiar and recognisable. That is partly because his war was the war that a million men like him knew and endured and has become part of our historic consciousness; but more than that it is because Charlie May is ‘England’ as England has always liked to imagine itself, the England that stood in square at Waterloo and would stand waist-deep in water at Dunkirk, the England of a hundred 1940s and ’50s films, down to his English wife and his English baby daughter and the English batman and the Alexandra rose that he sports into battle – the unassuming, modest, enduring, reliable, immensely likeable kind of Englishman, with his kindness, his tolerance, his loyalty, his certainties, his prejudices, his pipe, his fishing rod, his horse, his good jokes and his bad jokes and his un-showy patriotism, that if you had to spend your war up to your knees in clinging mud you would be very grateful to find next to you: and he is absolutely genuine.

I do not know if it is odd that someone so quintessentially English should come from New Zealand, or if that is part of the explanation, but Charlie May was born in that most stonily un-English of towns, Dunedin, on 27 July 1888, the son of an electrical engineer who had emigrated five years earlier. His father made his name and the foundation of a successful business with a patent for a new kind of fire alarm device, and on their return to England, Charlie had entered the family firm of May-Oatway, acting as company secretary before moving with his new wife, Maude, from the Mays’ family home overlooking Epping Forest to Manchester where, just two weeks before the outbreak of war in 1914, a daughter, Pauline, was born. It is clear that the Mays did not lose sight of their New Zealand lives – their Essex home was named ‘Kia Ora’ (‘be well’ in Maori) and Charlie would call his new home ‘Purakaunui’, after a pretty coastal settlement, near Dunedin – but in 1914 there would have felt nothing odd about such a double identity. It was famously said that sometime between the landing at Anzac Cove and the end of the Battle of the Somme the New Zealand nation was born, but in the late summer of 1914, before Gallipoli was ever dreamed of, many of the thousands of New Zealanders who volunteered to fight in a war half a world away would have seen themselves as part of a single imperial family, one corner of the great Dominion ‘quadrilateral’ of Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, on which the British Empire rested.

While still in the south May had been a member of King Edward’s Horse, a Territorial unit of the London Mounted Brigade with strong Dominion links, and, daughter or not, it was only a matter of time before war put an end to his short married idyll. On the outbreak of hostilities five divisions of a small but highly trained British Expeditionary Force had immediately been embarked for France to stem the German advance, but Kitchener for one never had any illusions that this was going to be a short war over by Christmas and within the month the first 300,000 of a New Army had responded to his call for volunteers.

By the end of September another 450,000 had volunteered, in October a further 137,000, and in the following month Charlie May enlisted into the 22nd Manchester Pals battalion – the ‘7th City Pals’ – and added his name to the five million men who would wear uniform of one sort or another before the war was over. The idea of the ‘Pals battalions’ had first been put to the test in Liverpool by Lord Derby and the city of Manchester enthusiastically followed suit, embracing the patriotic and civic ideal of a battalion made up of friends from the same street, pub, factory, profession, warehouse or football club, joining up and fighting together – ‘clerks and others engaged in commercial business,’ as Derby put it, ‘who wish to serve their country and would be willing to enlist in a Battalion of Lord Kitchener’s new army if they felt assured that they would be able to serve with their friends and not to be put in a Battalion with unknown men as their companions’.

It was a sympathetic initiative, if a double-edged one as time would bitterly show, but in the late summer of 1914, as towns across Britain competed with each other in displays of civic pride, the slaughter that would engulf whole tightly knit communities in grief still belonged to an unimaginable future. Within hours of the Lord Mayor of Manchester launching his appeal in the Manchester Guardian on 31 August, volunteers were besieging the artillery barracks on Hyde Road and by the end of the next day 800 men had been sworn in and the establishment of the first of the Manchester Pals battalions, the 1st ‘City’, or 16th Service, was complete. Over the next four days another two battalions were added, and after a late summer lull in recruiting caused by the frustrating long queues, a further three battalions in November, the 20th, 21st and Charlie May’s 22nd under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Cecil de C. Etheridge.

It would be exactly a year before Charlie May and his battalion embarked for France, and in that time an enthusiastic but improbable bunch of men drawn largely from the cotton industry and City Corporation – ‘mostly town bred’, wrote May, with a rare whiff of the King Edward’s Horse and the Empire – had to be turned into soldiers. In these early stages before their khaki uniforms arrived, they wore the ‘doleful convict-style’ ‘Kitchener Blue’ and ‘ridiculous little forage cap’ so deeply resented among the New Army, but over the next twelve months, and in the face of the universal shortages of uniforms, weapons and ammunition and every provocation and indignity an army could dream up to frustrate, bore or disillusion a civilian volunteer, the job was at least begun.