По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

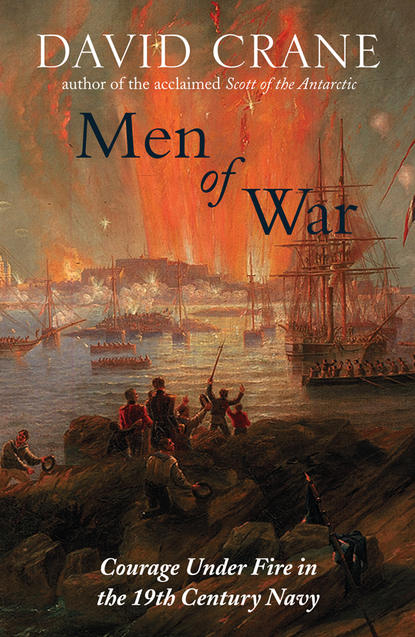

Men of War: The Changing Face of Heroism in the 19th Century Navy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

If ever a man was doomed by birth it was Frank Abney Hastings. In the weeks and months after the Kangaroo incident, there was scarcely a day when one word of apology could not have saved his career, when a single gesture of moderation or even cautious self-interest could not have redeemed his reputation; but he was quite simply incapable of making it. ‘Your Lordship may find officers that will submit to such language,’ he wrote instead to Lord Melville, the First Lord of the Admiralty,

but I don’t envy them their dear purchased rank & God forbid the British Navy should have no better supporters of its character than such contemptible creatures. A great stress has been layed upon the circumstance of the challenge being delivered to Capt Parker on the Quarter deck, but … why the contents of a sealed challenge should be known to bystanders any more than the contents of a dinner invitation I confess myself at a loss to divine.

If this was hardly the language of conciliation or compromise, the truth was that there was nothing in Hastings’s temperament or background that would have counselled a place for either. For six hundred years the Hastings family had amassed titles and lands with a daring promiscuity, alternately the favourites and the victims of successive English monarchs to whom they were too closely related for comfort, safety or humility. ‘Though the noble Earl was sprung from ancestors the most noble that this Kingdom could boast,’ the Gentleman’s Magazine wrote in 1789 on the death of Frank’s grandfather, the 10th Earl of Huntingdon,

Plantagenet, Hastings, Beauchamp, Neville, Stafford, Devereux, Pole, Stanley, it might be said also that they were most unfortunate. The Duke of Gloucester was strangled at Calais. The Duke of Clarence was put to death privately [fine word, ‘private’] in the Tower. The Countess of Salisbury, his daughter, was publicly beheaded, as was also her son … Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, was beheaded by Richard III. Robert Devereux, the famous Earl of Essex, died on a scaffold in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. The untimely deaths of the gallant Nevilles are sufficiently known. The founder of the Huntingdon family, William Lord Hastings, lost his head in the Tower …

No family that includes Warwick the Kingmaker and Essex can put such a record entirely down to ill-luck, and it sometimes seems as if the Hastings went out of their way to import vices that were not already indigenous to the tribe. From the sixteenth century onwards there had been a distinct streak of religious extremism in the family, and in the seventeenth fanaticism was wedded to real madness with the marriage of the 5th Earl to Lucy Davies, a niece of the Lord Castlehaven beheaded for sodomy and abetting the rape of his wife, and the devoted daughter of that notorious prophetess, Bedlamite and ‘abominable stinking great Symnell face excrement’ of Stuart England, Lady Eleanor Davies.

To marry into one unstable family might be a misfortune, but to marry into two smacks of something more culpable, and to the toxic infusion of Castlehaven’s Touchet blood in the seventeenth century was added that of the Shirleys in the eighteenth. This latter alliance came at a time when some of the old Hastings energy seemed at last to be dissipating, but in the tyrannical and litigious Selina Shirley, Countess of Huntingdon – cousin of the Earl Ferrers hanged for murder, founder of the religious cult bearing her name and, by turns, Wesleyan, mystic, ritualist and damnation-breathing Calvinist – the Hastings could again boast a figure to hold her bigoted own with any in the family’s long and bloody history.

It is astonishing, in fact, how successfully the Hastings clan came through an Augustan age of Lord Chesterfield, ‘manners’ and rhyming couplets and emerged on the other side with all their traditions of violence and excess so wonderfully intact. In a letter to Warren Hastings – no relative but a close friend – Frank’s father once cheerfully confessed to their ‘naturally hot and spicy’ blood, and whether they were Calvinist or atheists, shooting themselves or shooting their steward, hanging rebels in America or being hanged at Tyburn, the young Frank’s immediate family bequeathed to him a tradition of volatility that found its inevitable echo in his challenge to Captain Hyde Parker.

Throughout his life Frank would be abnormally sensitive to the claims of a family that, in its more modest moments, traced its ancestry back ‘eleven hundred years before Christ’, and for him there was a twist that might well have added a morbid prickliness to the natural Hastings hauteur. From the first creation of the earldom in the sixteenth century the Huntingdon title had descended in more or less regulation mode to the middle of the eighteenth, but when the 9th Earl died of a fit of apoplexy in 1746, he was succeeded by a seventeen-year-old son whose well-publicised contempt for women of a marriageable class had soon eased him into the arms of the Parisian ballerina and ‘first dancer of the universe’, Louise – ‘La Lanilla’ – Madeleine Lany.

The result of that ‘Philosophical and merely sentimental commerce’, as his friend and moral guide Lord Chesterfield silkily put it, was a baby boy born on 11 March 1752. By the time this ‘young Ascanius’ arrived in the world ‘La Lanilla’ had already been abandoned, and while Huntingdon continued his philosophical and sentimental education on a diet of Spanish paintings and Italian women, the infant Charles was removed from France and sent over to Ireland to be brought up ‘as brothers’ with his cousin Francis Rawdon, the future 2nd Lord Moira in the Irish Peerage, Baron Rawdon in the English, 1st Marquis of Hastings and Governor General of India.

Of all the generations of Hastings who shaped Frank’s future, Charles Hastings – his father – is infinitely the most engaging. There seems little now that can be known of his early childhood, but in 1770 he was bought a commission in the 12th of Foot, and over the next twenty years enjoyed as successful a career as was possible at that nadir of British army fortunes, distinguishing himself in America and at the siege of Gibraltar before finally rising by purchase and patronage to the rank of lieutenant general and the colonelcy of his old regiment.

With the powerful Hastings connections behind him, the friendship of the Prince of Wales, and a pedigree and personality that might have been designed for the louche world of Carlton House, the only things missing from Charles’s life were the title that went into abeyance on the Earl’s death in 1789 and the fortune and family seat that passed to his Moira cousin. He would have to wait another sixteen years for the minor compensation of a baronetcy, but in the year after his father’s death he augmented his modest inheritance by marriage to a Parnell Abney, the sole daughter and heiress of Thomas Abney of Willesley Hall, a handsome but dilapidated estate with a landscaped park and ornamental lake just two miles south of the historical Hastings power base at Ashby-de-la-Zouch.

Charles was thirty-eight on his marriage, and still only forty-one in 1793 when war broke out with France, but to his deep frustration a Tory government could find no active use for him in the years ahead. The seven years between 1796 and 1803 were spent instead in command of the garrison on Jersey, and by the time his friends came into power, age, ill-health and a growing melancholy had reduced him to a kind of English version of Tolstoy’s old Prince Bolkonski, brooding in his library over his maps and despatches as Bonaparte’s armies redrew the boundaries of Europe.

It is hard to imagine what solace a world-weary free-thinker can have found in Parnell Hastings – ‘a great bore’ is the only surviving judgement on her – but the one thing they shared was a deep love of their two surviving children. It would seem that their eldest, Charles, was always closer to his mother than to his father, but if there were times when the old general thought a good dose of peppers in the boy’s porridge would cure him of his ‘milk-sop’ tendencies, there were no such fears over his younger and favourite lad, Frank, born in 1794 and destined from an early age for a career in the navy.

With his father’s royal and military connections – Lord Rawdon was Commander-in Chief for Scotland and Sir John Moore a close friend – it seems odd that Frank did not follow him into the army, and odder still when one remembers the grim reality of naval life in 1805. In May 1803 the brief and bogus Peace of Amiens had come to its predictable end, and for the two years since Britain’s weary and overstretched navy had struggled from the Mediterranean narrows to the North Sea to contain the threat of the French and Spanish fleets while the country steeled itself for invasion.

It is only in retrospect that 1805 seems the year to go to sea, because with Napoleon abandoning his invasion plans, and the allied fleets holing up in Cádiz after their West Indies flirtation, the only certain prospect facing Frank as his father took him down to Plymouth was the ‘long, tiresome and harassing blockade’ work that had become the navy’s stock in trade. ‘I think it incumbent upon me to announce to you the disposal of my boy,’ a grateful Charles Hastings wrote to Warren Hastings on 11 June 1805, a month after entering Frank as a Volunteer First Class under the command of one of Nelson’s most bilious, courageous and uxorious captains, the solidly Whig Thomas Fremantle, ‘whom you were so kind as to patronize by writing to Lord St Vincent. He is at present with the Channel fleet on board the Neptune of 98 guns commanded by my friend Captain Fremantle. We have heard from him since, and he is so delighted with his profession that he declares nothing shall ever tempt him to quit it – I took him down to Plymouth myself.’

It would be hard to exaggerate how alien and hermetic a world it was that closed around the young Hastings when his father deposited him at Plymouth. As a small child growing up on Jersey he would have been familiar enough with garrison life, but nothing could have prepared him for the overpowering strangeness of a great sea-port during wartime, its utter self-sufficiency and concentration of purpose, its remoteness from the normal rhythms of national life, its distinctive mix of chaos and order, its forest of masts and myriad ships’ boats, or the sheer, outlandish oddity of its inhabitants. ‘The English keep the secrets of their navy close guarded,’ the young Robert Southey, masquerading in print as the travelling Spanish nobleman Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella, wrote two years later of his attempt to penetrate the sealed-off worlds of Britain’s historic ports. ‘The streets in Plymouth are swarming with sailors. This extraordinary race of men hold the soldier in utter contempt, which with their characteristic force, they express by this scale of comparison, – Mess-mate before ship-mate, ship-mate before a stranger, a stranger before a dog, and a dog before a soldier.’

At the outbreak of the Napoleonic War the Royal Navy was quite simply the largest and most complex industrialised organisation in the world, and it was in the great south coast ports of Plymouth or Portsmouth that this took on its most overwhelming physical expression. ‘A self-contained walled-town,’ wrote Caroline Alexander in her magical evocation of the dockyards that serviced the world’s greatest fleet – eighty-eight ships of the line in commission the year Frank joined, thirteen ‘Fifties’, 125 frigates, ninety-two sloops, eighteen bombs, forty gunbrigs, six gunboats, eighty-two cutters and schooners and forty-one armed ships,

the great yard encompassed every activity required to send ships to sea … There were offices and storehouses, and neat brick houses … as well as the massive infrastructure required to produce a ship. In the Rope-house all cordage was spun, from light line to massive anchor cable, in lengths of more than a thousand feet, some so thick that eighty men were required to handle them … Timber balks and spires of wood lay submerged in the Main Pond, seasoning until called to use. In the blacksmith’s shop were wrought ninety hundred-weight anchors in furnaces that put visitors in mind of ‘the forge of Vulcan.’ And on the slips, or docked along the waterfront, were the 180-foot hulls of men-of-war, the great battle-wounded ships brought for recovery, or the skeletons of new craft, their hulking, cavernous frames suggesting monstrous sea animals from a vanished, fearsome age.

Along with all this industrial might came the people, the contractors and tradesmen, the wives and prostitutes, the shopkeepers and clerks, and the thousands of workers who kept the fleets at sea. ‘I could not think what world I was in,’ another boy recalled his introduction to this alien culture, ‘whether among spirits or devils. All seemed strange; different language and strange expressions of tongue, that I thought myself always asleep or in a dream, and never properly awake.’

If it was an alien world, though, with its own language and languages – England, Ireland, Canada, America, the Baltic, Spain, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Martinique, Sardinia, Venice, they were all represented in Neptune – its own customs, and traditions, its own time-keeping, arcane ways of business and overlapping hierarchies, it was a world the young Hastings took to as if he had known no other. ‘Whilst on board with him (although only eleven years old last month),’ Sir Charles proudly told Warren Hastings, ‘he offered to go up the masthead without going through the Lubbers’ hole which however Capt Fremantle would not permit as I could not have borne seeing him make the attempt – I have no doubt that he will do very well if his education is not neglected but as there is a Schoolmaster on board I entertain great hopes of him making a proficiency.’

There were thirty-four boys in all entered in Neptune’s muster book – the youngest nine years old (there was a four-year-old girl in Victory, born in HMS Ardent in the middle of the Battle of Copenhagen) – though only a handful rated ‘Volunteer First Class’ who were destined to be officers. There was still such a wide divergence of practice from ship to ship that it is impossible to generalise about these boys’ duties, but in a world of interest and patronage, the naturally symbiotic relationship of captain and volunteer was a well-connected boy like Hastings’s best guarantee of the training his father had wanted for him. ‘My Dear General,’ – that ‘most mischievous political quack … Mr Pitt’ was still alive and the general as yet without his baronetcy – Captain Fremantle was soon writing to Frank’s father, conscientiously carrying out his side of the bargain: ‘… of your boy I can say nothing but what ought to make you and Mrs Hastings very happy, he is very mild and tractable, attentive to his books & dashing when with the youngsters of his own age. I declare I have had no occasion to hint even anything to him, as he is so perfectly well behaved.’

With all the ‘dash’ and patronage in the world, a man-of-war like Neptune, with her 116 marines and ship’s company of 570 brawling, drunken, thieving seamen recruited or pressed from across the globe, was a tough school for any boy. ‘Who can paint in words what I felt?’ Edward Trelawny, whose path would later cross with Hastings’s in Greece, histrionically recalled his first days as a thirteen-year-old midshipman in that summer of 1805. ‘Imagine me torn from my native country, destined to cross the wide ocean, to a wild region, cut off from every tie, or possibility of communication, transported like a felon, as it were, for life … I was torn away, not seeing my mother, or brothers, or sisters, or one familiar face; no voice to speak a word of comfort, or to inspire me with the smallest hope that anything human took an interest in me.’

Trelawny had his own sub-Byronic line in self-pity and self-dramatisation to peddle, but even in Neptune and under a captain like Fremantle, there were no soft edges to the gunroom. ‘I thought my heart would break with grief,’ William Badcock, a fellow ‘mid’ in Neptune when Hastings joined, recalled. ‘The first night on board was not the most pleasant; the noises unusual to a novice – sleeping in a hammock for the first time – its tarry smell – the wet cables for a bed carpet … Time however reconciles us to everything, and the gaiety and thoughtlessness of youth, added to the cocked hat, desk, spy-glass, etc of a nautical fit out, assisted wonderfully to dry my tears.’

And for all the brutal horseplay – ‘sawing your bed-posts’, ‘reefing your bed-clothes’, ‘blowing the grampus’ (sluicing a new boy with water) – and the ever-present threat of the ‘sky parlour’ or masthead for punishment, there was none of the institutional or private tyranny in Neptune so vividly recorded in Trelawny’s Adventures of a Younger Son. A midshipman coming off watch might spend his first half-hour unravelling his tightly knotted blanket in the dark, but with cribbage and draughts to play, book work to be done and stories of Captain Cook to be wheedled out of the old quartermaster, Badcock did his ‘fellows in Neptune the justice to say that a more kind-hearted set was not to be met with’.

Hastings did not have long in Plymouth to acclimatise himself to this new world. On 17 May, after a hasty refit, the Neptune was ready again for sea. ‘I begin my journal with saying that I have passed as miserable a day and night as I could well expect,’ Fremantle complained to his wife Betsey the same night, as his sluggish-handling new ship pitched and rolled in heavy seas and Plymouth, home and family slipped below the horizon:

tho’ I have no particular reason why that should be the case … I dined with young Hastings only on a fowl and some salt pork, as triste as a gentleman needs to be … my mind hangs constantly towards you and your children, and I am at times so low I cannot hold up my head … my only hope is in a peace, which I trust in God may be brought about through the mediation of Russia. These French rascals will never come out and fight but will continue to annoy and wear out both our spirits and constitutions.

This two-month cruise with the Channel Squadron gave Hastings his first experience of blockade work, and after another brief refit at Plymouth he was soon again at sea. Fremantle had no more real belief in bringing the French out to battle than he had ever had, but by 3 August they were once more off Ushant and before the end of the month had joined Collingwood’s growing squadron blockading the enemy fleets inside Cádiz. ‘I am in hope Lord Nelson will come here as nobody is to my mind so equal to the command as he is,’ Fremantle wrote to his wife on 31 August:

it will require some management to supply so large a force with water and provisions, and as the combined fleets are safely lodged in Cadiz, here I conclude we shall remain until Domesday or until we are blown off the Coast, when the French men will again escape us. I can say little about my Ship, we go much as usual and if any opportunity offers of bringing the Enemy’s Fleet to battle, I think she will show herself, but still I am not half satisfied at being in a large Ship that don’t sail and must be continually late in action.

They might well have stayed there till doomsday, but while Fremantle fretted and flogged, a messenger was already on the road to Cádiz with orders for the French Admiral Villeneuve to take the fleet into the Mediterranean in support of the Emperor’s new European ambitions. From the collapse of the Peace of Amiens Napoleon’s naval strategy had been marked by an utter disregard for realities, but this time he had excelled himself, timing his orders to arrive on the very day before Fremantle and the whole blockading fleet at last got their wish for Nelson. ‘On the 28th of September was joined by H.M. Ship Victory Admirl Lord Nelson,’ wrote James Martin, an able seaman in Neptune, ‘and the Ajax and the Thunderer it is Imposeble to Discribe the Heartfelt Satifaction of the whole fleet upon this Occasion and the Confidance of Success with which we ware Inspired.’

‘I think if you were to see the Neptune you would find her very much altered since you were on bd,’ Fremantle told Frank’s father, sloth, dyspepsia and ill-temper all dispersed by a single dinner with Nelson and the promise of the second place in the line in any coming action. ‘We are all now scraping the ship’s sides to paint like the Victory [black, with buff-coloured stripes running between the portholes], the fellows make such a noise I can hardly hear myself. Pray make my respects to Mrs Hastings & beg her [to have] no wit of apprehension about her son who has made many friends here, & who is able to take his own part.’

Opinions were still divided as to whether or not the French would come out, but with five ‘spy’ frigates posted close in to the city, and Nelson’s battle plan circulated among the captains, the fleet knew what was expected of them. In the brute simplicity of the tactics Hastings was to learn an invaluable lesson, but the great danger of breaking the line in the way Nelson intended was that it ceded the opening advantage to the enemy, exposing a sluggish handler like Neptune in the light October breezes to the full enemy broadsides for anything up to twenty minutes before she could get beneath a foe’s vulnerable stern.

Nobody in Neptune was under any illusion as to what that would mean, but nothing could contain the excitement when the signal from the inshore squadron finally came. ‘All hearts towards evening beat with joyful anxiety for the next day,’ Badcock wrote on 20 October, as Neptune answered the signal for a general chase, ‘which we hoped would crown an anxious blockade with a successful battle. When night closed in, the rockets and blue lights, with signal guns, informed us the inshore squadron still kept sight of our foes, and like good and watchful dogs, our ships continue to send forth occasionally a growly cannon to keep us on the alert, and to cheer us with the hope of a glorious day on the morrow.’

As partitions, furnishings and bulkheads were removed, decks cleared, livestock slaughtered – Fremantle had a goat on board that had provided him with milk – Neptune turned south-west to give her the weather gage in the coming action. From the signals of their ‘watchdogs’ they knew that the enemy were still moving in a southerly direction, and as dawn broke on 21 October, first one sail and then a whole ‘forest of strange masts’ appeared some eleven miles to leeward to show that the Combined Fleet was at last where Nelson wanted it.

The sun, William Badcock – midshipman of the forecastle and first in Neptune to see the enemy – remembered, ‘looked hazy and watery, as if it smiled in tears on many brave hearts which fate had decreed should never see it set … I ran aft and informed the officer of the watch. The captain was on deck in a moment, and ere it was well light, the signals were flying through the fleet to bear up and form the order of sailing in two columns.’

As the ship slipped into those atavistic rhythms that no one who witnessed them ever forgot, and hammocks were stowed, cutlasses and muskets distributed, powder horns and spare flintlocks issued, magazines and powder rooms unlocked, operating area prepared, and final letters written, full sail was set and Neptune strove to take her place in the line. In Nelson’s original battle plan Fremantle had been ordered to follow Temeraire, Superb and Victory in the weather division, but with only the short October day ahead of them, and speed crucial if the enemy were not to escape, precedence went out of the window in favour of an ad hoc order that left the two columns to sort themselves out, as sailing capacities dictated, behind Victory and the Royal Sovereign.

It was now that the ‘old Neptune, which never was a good sailer’, as William Badcock put it, ‘took it into her head to sail better that morning than I ever remembered’, and at about 10 a.m. she came up alongside Nelson’s Victory. Fremantle intended to ‘pass her and break the enemy’s line’, Badcock recalled, ‘but poor Lord Nelson hailed us from the stern-walk of the Victory, and said, “Neptune, take in your studding-sails and drop astern; I shall break the line myself.”’

It was probably the eleven-year-old Hastings’s sole glimpse of Nelson, but if he ever wondered what it was that gave him his unique hold over men, he did not have long to wait for an answer. As Neptune dropped astern of Victory, and the Temeraire slipped between them to take her place in the van, Nelson’s last signal before the order to ‘engage’ was relayed through the fleet. ‘At 11,’ the Neptune’s log laconically noted, ‘Answered the general signal, “England expects every man will do his duty”; Captain Fremantle inspected the different decks, and made known the above signal, which was received with cheers.’

He ‘addressed us at our Different Quarters in words few’, James Martin remembered, ‘but Intimated that … all that was Dear to us Hung upon a Ballance and their Happyness depended upon us and their safty allso Happy the Man who Boldly Venture his Life in such a Cause if he shold Survive the Battle how Sweet will be the Recolection be [sic] and if he fall he fall Covred with Glory and Honnor and Morned By a Greatfull Country the Brave Live Gloryous and Lemented Die.’

In the heavy swell and light winds – and to the sounds of ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Britons Strike Home’ drifting across the water from ships’ bands – Neptune closed on the enemy with agonising slowness. ‘It was a beautiful sight,’ Badcock wrote,

when their line was completed; their broadsides turned towards us, showing their iron teeth, and now and then trying the range of a shot to ascertain the distance, that they might, the moment we came within point blank (about six hundred yards), open the fire upon our van ships … Some of them were painted like ourselves – with double yellow sides, some with a broad single red or yellow streak; others all black, and the noble Santissima Trinidada (158), with four distinct lines of red, with a white ribbon between … her head splendidly ornamented with a colossal group of figures, painted white, representing the Holy Trinity … This magnificent ship was destined to be our opponent.

It was not just a ‘beautiful sight’, but an exhilarating and terrifying one, and at the stately walking pace at which the fleets closed there was all the time in the world to take it in. At 11.30 Neptune’s log at last recorded the signal ‘to locate the enemy’s line, and engage to leeward’, and as first Victory and then Temeraire broke through ahead, and Neptune prepared to receive her opening broadsides, Fremantle ordered everyone, except the officers, to lie down to reduce casualties.

Until this moment Hastings had been on the quarterdeck with Fremantle, an unusually small, frightened and superfluous spectator, neatly dressed in the new suit Betsey Fremantle had had made for him, but to his future chagrin the First Lieutenant now ordered him to a safer circle of hell below. ‘A man should witness a battle in a three-decker from the middle deck,’ a young marine lieutenant in Victory later wrote, struggling to evoke the blind, smoke-filled, deafening chaos of the battle that awaited Hastings as he made his way down to the lower decks of Neptune,

for it beggars all description: it bewilders the senses of sight and hearing. There was the fire from above, the fire from below, besides the fire from the deck I was upon, the guns recoiling with violence, reports louder than thunder, the decks heaving and the sides straining. I fancied myself in the infernal regions, where every man appeared a devil. Lips might move, but orders and hearing were out of the question, everything was done by signs.

Even to those still on the quarterdeck, the smoke of battle and the tangle of fallen masts and rigging had already obscured Victory, but as Neptune closed on her target, the gap that Nelson had punched between Villeneuve’s Bucentaure and Redoubtable widened to welcome her. For the final ten minutes of her approach Neptune was forced to take the combined fire of three enemy ships, until at 12.35 she at last broke through astern of Bucentaure and, in the perfect tactical position, delivered a broadside from thirty yards’ range. ‘At 12.35, we broke their line,’ the log reads – a typical mix of understatement, spurious accuracy, guesswork and partial knowledge.

At 12.47, we engaged a two-deck ship, with a flag at the mizzen. At 1.30, entirely dismasted her, she struck her colours; and bore down and attacked the Santa Trinidada, a Spanish four-decker of 140 guns … raked her as we passed under her stern; and at 1.50 opened our fire on her starboard quarter. At 2.40, shot away her main and mizzen masts; at 2.50, her foremast; at 3, she cried for quarter, and hailed us to say they had surrendered; she then stuck English colours to the stump of her main mast; gave her three cheers.

Neptune herself was in little better shape – ‘standing and running rigging much cut; foretop-gallant and royal yard shot away … wounded in other places; fore yard nearly shot in two, and ship pulled in several places’ – but as the smoke cleared they caught their first overview of the shambles around them. ‘We had now Been Enverloped with Smoak Nearly three Howers,’ wrote James Martin. ‘Upon this Ships [Santa Trinidada] striking the Smoak Clearing a way then we had a vew of the Hostle fleet thay were scattred a Round us in all Directions Sum Dismasted and Sum were Compleat wrecks Sum had Left of Fireng and sum ware Engagen with Redoubled furey it was all most imposeble to Distinguish to what Nation thay Belonged.’

It was a momentary respite – ‘but a few minets to take a Peep a Round us’ – but in the midst of this chaos they could see Victory and Temeraire still ‘warmly engaged’ and, more critically, ‘the six van ships of the enemy bearing down to attack’ them. In his original memorandum Nelson had anticipated this second phase of the battle, and as separate ship-actions continued to the rear of them, Neptune, Leviathan, Conqueror and Agamemnon manoeuvred to form a rough line of defence. ‘At 3.30, opened fire on them,’ Neptune’s log continued, ‘assisted by the Leviathan and Conqueror; observed one of them to have all her masts shot away by our united fire.’

With nearly all her own sails shot away, however, and not ‘a brace or bowline left’, Neptune was in no state to give chase when the remaining enemy abandoned their attack and escaped to southward. For another hour or so the fight continued around them in a mix of close actions and long-range duels, but for Neptune – and, at 4.30, just a quarter of an hour after she had ceased firing, Nelson himself – the battle was over. ‘Three different powers to rule the main,’ ran a popular song reflecting on the fate of the three ‘Neptunes’ that had fought at Trafalgar,

Assumed old Neptune’s name:

One from Gallia, one from Spain,