По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

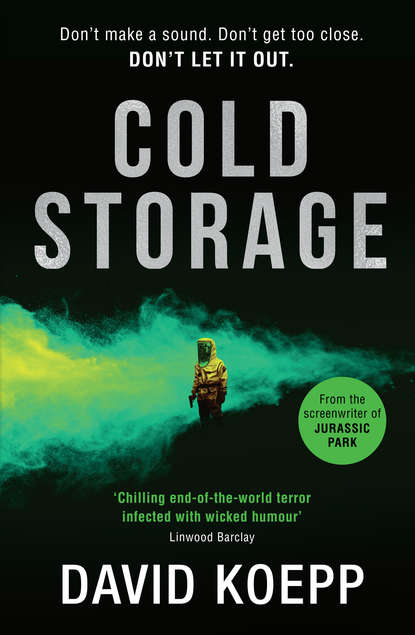

Cold Storage

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Griffin revved the bike and pulled his goggles down. He shouted something at Teacake as he dropped the bike in gear, just two words, but here’s where Griffin’s essential nature as an asshole came in again—he’d hooked up a noncompliant straight-pipe exhaust on his bike to make it extra loud and annoying to the rest of the world, so there was really no shot at all that his words would be understood over it. To Teacake it sounded like he yelled “Monday’s bleeding,” but in fact what his boss had shouted was “Something’s beeping.”

Teacake would find that out for himself soon enough.

THE FACT THAT GRIFFIN WAS PUT IN CHARGE OF ANYTHING WAS A JOKE, because not only was he dumb, racist, and violent, but he was a raging alcoholic to boot. Still, there are alcoholics and there are functioning alcoholics, and Griffin managed to be the latter by establishing a strict drinking regimen and sticking to it with the discipline of an Olympic athlete. He was dead sober for three and a half days of the week, Monday through Wednesday, when he worked the first three of his four twelve-hour shifts, and he didn’t start drinking until just before six P.M. on Thursday. That, however, was a drunk that he would build and maintain with fussy dedication, starting right now and continuing through his long weekend until he passed out on Sunday night. Really, the Monday hangover was the only hard part, but Griffin had been feeling them for so long now they just seemed like part of a normal Monday morning. Toast, coffee, bleeding from the eyeballs—must be a new workweek.

Griffin was born over in Council Bluffs and spent six years working in a McDonald’s in Salina, where he’d risen to the rank of swing manager. It was a tight little job, not least because of the tight little high school trim that he had the power to hire and fire and get high with in the parking lot after work. Griffin was an unattractive man—that was just an objective reality. He was thick as a fireplug, and his entire body, with the notable exception of his head, was covered with patchy, multicolored clumps of hair that made his back look like the floor of a barbershop at the end of a long day. But the power to grant somebody their first actual paying job and to provide the occasional joint got him far in life, at least with sixteen-year-olds, and when he was still in his not-quite-midtwenties. Soon enough the sixteen-year-olds would wise up and the last of his hair would go and his “solid build” would give way to what could only be called a “fat gut,” but for those few years, in that one place, Griffin was a king, pulling down $24,400 a year, headed for a sure spot at Hamburger U, the McDonald’s upper management training program. And nailing underage hotties at least every other week.

Then those little fuckers, those little wise-ass shitheads who didn’t really need the job, who just got the job because their parents wanted them to learn the Value of Work, those little douchebags from over in the flats—they ruined everything. They were working drive-through during a rush when it happened. Why Griffin had ever scheduled them in there together is beyond him to this day; he must have been nursing a wicked hangover to let those two clowns work within fifty feet of each other, but they started their smart-ass shit on the intercom. They’d take orders in made-up Spanish, pretend the speaker was cutting in and out, declare today “Lottery Day” and give away free meals—all that shit that’s so hilarious because real people’s jobs don’t mean anything, not when you’re going to Kansas State in the fall with every single expense paid by Mommy and Daddy, and the only reason this job will ever turn up on your résumé is to show what a hardworking man of the people you were in high school. There they are, your fast-food work dues, fully paid, just like your $10,000 community service trip to Guatemala, where you slowed down the building of a school by taking a thousand pictures of yourself to post on Instagram.

On that particular day there was a McDonald’s observer from regional in the parking lot, a guy taking times on the drive-through and copious notes on the unfunny shenanigans going on in there. The good-looking creep—the smarmy one, not the half-decent redheaded kid who just went along with the bullshit, but the handsome fucker, the one who was sleeping with the window girl in the docksiders whom Griffin himself could never get to even look at him—that kid knew the guy was out there. And he sat on that nugget of information for a good half hour, until he finally smirked past the office and said, “Oh, hey, there’s a McDonald’s secret agent man parked out by the dumpster.”

Griffin was demoted to grill the next day, and he quit before he ended up at the fry station. He had the job at Atchison Storage three weeks later, and when the current manager there moved to Leawood to get married, Griffin inherited the fourteen-dollar-an-hour job, which, if he never, ever took a week off, meant $34,000 a year and three free days a week to get wasted. He also figured he could pull in another $10K in cash for housing the Samsungs and other items of an inconvenient nature that showed up needing a temporary home from time to time. The previous manager had clued him in about the side gig, which Griffin understood was a common perk of the self-storage management community. Hang on to this stuff, let people pick it up, take a cut of whatever it sells for. Zero risk. All in all, it was a decent setup, but not half as good as what could have been. He could have had a career in management, real management. Sitting at a desk all day so you can help a parade of freaks and hillbillies get access to their useless shit is a hell of a lot different from presiding over a constant parade of job-seeking teenage sluts. But you takes what you can takes. Atchison, Kansas, was not a buffet of career opportunity.

Despite everything that happened, Griffin’s only regret in life so far was that he could never get anyone to agree to call him Griff. Or G-Dog. Or by his goddamn first name. All the man wanted was a nickname, but he was just Griffin.

TEACAKE PUNCHED IN BEHIND THE FRONT DESK. HE HEARD THE BEEP, but he didn’t hear the beep; it was one of those things. Whatever the part of your brain is that registers an extremely low-volume, high-pitched tone that comes once every ninety seconds, it was keeping the news to itself for the first half hour he was at the desk. The faint beep would come, it would register somewhere in the back of his mind, but then it would be crowded out by other, more pressing matters.

First, he had to check the monitors, of which there were a dozen, to make sure the place was clean and empty and as barren and depressing as always. Check. Then a quick glance over at the east entrance to see if She had shown up for work yet (she had) and to think for a second whether there was any plausible reason to orchestrate running into her (there wasn’t). There was also the stink. Griffin was never a big one for tidying up, and the trash can was half full of Subway wrappers, including a former twelve-inch tuna on wheat, from the smell of it, and the reception area reeked of old lunch. Somebody would have to do something about that—twelve hours with tuna stench would be a long-ass shift. And finally, there was a customer, Mrs. Rooney, coming through the glass front doors, all frazzled and testy and all of a sudden.

“Hey, Mrs. Rooney, what up, you staying cool?”

“I need to get into SB-211.”

Teacake was not so easily deterred. “It’s hot out, right? Like Africa hot. Weird for March, but I guess we gotta stop saying that, huh?”

“I need to get in there right quick.”

In unit SB-211 Mary Rooney had twenty-seven banker’s boxes filled with her children’s and grandchildren’s school reports, birthday cards, Mother’s Day cards, Father’s Day cards, Christmas cards, and all their random notes expressing overwhelming love and/or blinding rage, depending on their proximity to adolescence at the time of writing. She also had forty-two ceramic coffee mugs and pencil jars made at Pottery 4 Fun between 1995 and 2008, when her arthritis got bad and she couldn’t go anymore. That was in addition to seven nylon duffel bags stuffed with newspapers from major events in world history, such as coverage of the opening ceremonies of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, and a vinyl Baywatch pencil case that was stuffed with $6,500 in cash she was saving for the day the banks crashed For Real. There were also four sealed moving boxes (contents long forgotten), so much old clothing that it was best measured by weight (311 pounds), and an electric metal coffeepot from 1979 that sat on top of the mountain of other crap like a crown.

At this moment Mrs. Rooney had two shoeboxes under her arm and that look on her face, so Teacake buzzed the gate that led to the storage units with no further attempt at pleasantries. Let the record show, though, that the heat that day was most certainly worthy of comment: it had been 86 degrees in the center of town at one point. But whatever, Mary Rooney needed to get into her unit right quick, and between her stuff and Mary Rooney you had best not get.

Teacake watched her on the monitors, first as she passed through the gate, then into the upper west hallway, her gray perm floating down the endless corridor lined with cream-colored garage doors, all the way to the far end, where she pushed the elevator button and waited, looking back over her shoulder twice—Yeah, like somebody’s gonna follow you and steal your shoeboxes filled with old socks, Mary—and he kept watching as she got into the elevator, rode down two levels to the sub-basement, stepped off, walked halfway down the subterranean hallway in that weird, shuffling, sideways-like-a-coyote stride of hers, and slung open the door on unit SB-211. She stepped inside, clicked on a light, and slammed the door shut behind her. She would be in there for hours.

When you find yourself staring glassy-eyed at a bank of video monitors, watching as a moderately old lady makes her slow and deliberate way through a drab, all-white underground storage facility so she can get to her completely uninteresting personal pile of shit—when you do this with no hope whatsoever that this lady will do anything even remotely interesting, that is the moment you’ll know you’ve bottomed out, entertainment-wise. Teacake was there.

And then everything changed.

His eyes had fallen on the upper right-hand screen, in the corner of the bank of monitors, the one that covered the other guard desk, on the eastern side of the facility.

Naomi was on the move.

The cave complex was enormous and cut right through the heart of the bluffs, so to save the trucks from Kansas City having to drive all the way around Highway 83 to Highway 18 to Highway E, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had cut in two entrances, one each on the eastern and western sides of the massive chunk of rock. As a result, Atchison had two reception areas and two people working the place at any given time, although they had different sections to monitor, so running into your co-worker almost never happened.

Unless you made it happen, which Teacake had been trying to do for two weeks now, since the day Naomi started. Her schedule was erratic—he could never put his finger on when she was going to be working and when she wasn’t—so he’d tried to just keep an eye on the monitors and engineer a run-in, but it hadn’t happened yet. There’d been a few times she was doing rounds when he almost took a shot at it, but when she was on the move he never knew where she was headed, so he hadn’t come up with a scenario that would have given him quite the right degree of natural. The place was so big that the only way to make it work would be to check her location and then go into a full-on sprint to get near her while she was still even remotely in the area. It would have been more hunting her down than running into her. There’s something about showing up breathless and sweaty for a “coincidental” bump-in with an attractive woman that is bound to come off as scary.

Now, however, opportunity was pounding on his door with both fists, because Naomi was walking down the long eastern main hallway with a full trash can under her arm, and that could mean only one destination: the loading dock, where the dumpsters were.

Teacake grabbed the brimming trash can from next to the reception desk—Thank you Griffin, you pig, you bet I’ll clean up your disgusting lunch—and he took off for the loading dock.

Six (#ulink_98bfa720-1bb1-5771-b79f-8c52616bc786)

Three things Naomi Williams knew about her mother—that she was smart, athletic, and had horrible taste in men. Worse, Naomi knew that she herself was exactly the same in all three respects. The difference was that Naomi had seen her mother’s mistakes, she’d watched them play out, one after another, as easily predictable slow-motion car wrecks. She was keenly aware of where each and every twist of the wheel and stomp of the brake had caused the careening momentum of her mother’s life to go into an unrecoverable spin. She knew from careful observation how to drive a life in order to crash it, and she was not about to make the same desperate moves with her own. She kept up her grades, she had decent extra-curriculars, and she knew what she wanted. She had planned and rehearsed her post–high school escape route so many times she could drive it in her sleep.

But then the night of graduation she got pregnant, and all that shit was out the window. Because she had to have the baby. It wasn’t her family who were the religious freaks; she and her mom and whoever her current stepfather was went to church on Christmas and for funerals, like most people did around here. But Mike’s family—Jesus Christ, no pun intended, the Snyders banged the God drum hard. That wasn’t unusual; there were a lot of religious people in this part of the country, ever since the big wave of evangelism that spread around the South and Midwest in the late 1970s. But the Snyders were born-again chest beaters, not the haunted, reliably depressive old kind of Catholic, but the joyful new kind of Catholic. They loved everybody. I mean, they really, actually loved you.

The Snyders had five kids, and though each one of them started out fairly normal and willing to grab the occasional beer or take a hit off a joint, by the time they hit fourteen or fifteen their parents had roped them into the family spiritual racket. It wasn’t like it was a scam or anything—they really meant it. Naomi thought it was cool at first; it was a lot of love and attention, way more than she got at home, and when she and Tara Snyder became best friends in eighth grade, Naomi started sleeping at their house two or three nights a week. Her own mother, distracted by her decaying third marriage, seemed grateful that Naomi had a place to go.

As the God love spread throughout the Snyder family over the next couple of years, Naomi and Tara managed to skate around it. Everybody’s got their familial role to play, and Tara was happy to be the wild child. She and Naomi drank too much, partied too much, and hung out with the wrong kinds of guys. But it was all working. Admittedly, it worked better for Naomi than for Tara. Naomi got mostly A’s in school without trying very hard, she could still score in the teens at a basketball game even if she’d been up most of the night drinking, and she’d already gotten into Tennessee-Knoxville with a kickass grant-and-aid package. Yes, she would finish with sixty grand in debt, but UT had a great veterinary program, and she’d be done and licensed and making at least that much per year in five and a half. If anybody had a right to party and sleep around a little, it was Naomi Williams. The God-loving stuff was something she was happy to fake, or even mean it a little sometimes, in exchange for the Snyder embrace, which was warm and undeniable, even in its sappiest and most suffocating forms.

God wasn’t the problem.

Mike Snyder was the problem.

He was two years older than Naomi and started hitting on her when she was about fifteen. Mike was something of a mythical figure around town. He had a reputation so thoroughly unearned that it defied reason, but there is almost no limit to what a person can achieve early in life when he has the total and unwavering support of a large and uncritical family. It’s later that it all turns back on you. But in his early years and in the Snyder view, Mike was an artist and interpretive dancer and brilliant musician. He was an immensely gifted child of God who must be given space and respect and freedom and money. Plus blow jobs, in Mike’s opinion. Naomi held off for a while, but he was so earnest, so tortured and pleading and clearly screwed up beyond his family’s ability to see, that she took pity on him. She knew it wasn’t right, it wasn’t how things were supposed to be, and looking back, she can’t believe she was ever so passive. Why did she feel this weird obligation to him that she didn’t feel to herself?

But she did. They’d go through periods where things would heat up and cool down; there were times she thought she loved him, times she was pretty sure she hated him, but most times she just felt vaguely bad for him. The kid knew he was an imposter even if he couldn’t come out and say it, and she wanted to make him calm down and leave her alone.

Mike never wanted intercourse, even when Naomi did, probably because he was tortured by the holdovers of the family’s start in rigid Catholicism. Mike was the oldest, the only one who’d gone to Catholic grade school, and the talons of guilt were sunk into him but good. There was no sexual encounter with Mike that was not wholly shot through with his crippling sense of shame. Naomi, whose own feelings toward physical love were about a billion times less complicated, didn’t press the issue. The last thing she needed was a short, unsatisfying coupling on the floor in the Snyder basement, followed by an image of Mike seared onto her eyeballs: Mike, naked, sobbing in the corner of the half-lit, deep-pile-carpeted basement; Mike, curled up over there next to the Addams Family pinball machine, rocking on his haunches and apologizing to God.

But that’s exactly what she got on graduation night.

Mike had been desperate to find some cultural or chronological benchmark by which he could move fucking Naomi into the realm of the Spiritually Acceptable, and he’d seized on her high school graduation with the fervor of a horny zealot. He planned his seduction for months. When the moment finally came, she was half-drunk, he was half-erect, and the result was All-World fumbly, but at least it was quick and now it was done. Naomi stared at him, over there in the corner, just a sad, twisted little kid, really. She still felt sorry for him, but mostly she felt relieved that this, at least, would never come up again.

So of course she got pregnant.

At that point Naomi made three huge mistakes in quick succession that altered the trajectory of her life. First mistake: she told Mike. Mike, she told, the Uncritically Loved Artistic Genius who was now twenty years old, still living in his parents’ house with no job, no plans for school, and no real artistic talent, a message that the world was in the process of tattooing on his forehead in the unloving and inconsiderate way that the world has with guys like him. But who else was she going to tell?

Strategically, it was hard to see that move for the gigantic tactical error that it was until it played out. Because Mike was overjoyed. Mike loved her. Mike wanted to marry her. And Mike immediately told his parents. That really threw Naomi; she rarely miscalculated when it came to guessing human behavior, but she missed this one by a mile. She’d assumed Mike—sobbing-naked-after-bad-sex Mike—would be overcome by remorse and do anything to keep his filthy secret to himself, but she didn’t consider the full impact of the adoration he had received all his short life. That, coupled with a terrifying early exposure to the ecstasy of the Catholic guilt-and-confession wash-and-dry cycle, made him a real loose cannon. The way Mike saw it, he’d been given a rare gift, the chance to do the right thing, and by God he was going to do it. His parents were similarly overjoyed—they had a couple of sinners to forgive, and it was time to get busy forgiving. The fact that Naomi was one of only a few hundred African Americans in Atchison to boot only made it better. It made them better.

Plus they’d all have a baby to raise. Everybody wins.

Mistakes two and three for Naomi fell fast after that first one, and they were things she failed to do rather than things she did. She failed to drive immediately to CHC in Overland Park to get an abortion, and she failed to tell Tara Snyder, who would have driven her immediately to CHC in Overland Park to get an abortion. Instead, she allowed the Snyder parents to sit her down and paint a picture of such joyous, multigenerational familial love around the presence of this new young life that it carried her through her first trimester and most of her second in conspiratorial silence. It wasn’t until her well-conditioned eighteen-year-old body finally started to show in the fifth month that she knew, for sure and for real, that she had made a massive mistake. But by then it was too late to do anything about it.

Sarah turned four the other day, and Naomi would be the first to tell you that she thanked God she had the kid after all. It was impossible to look at that little face and think otherwise, but that didn’t mean Naomi’s life was any better because things turned out this way. It was just different. Mike had taken off to join the Peace Corps within a week after the baby was born, and in truth that was a relief; he’d turned into a real pain in the ass once it sank in that Naomi wasn’t going to marry him, or sleep with him ever again. He would have made a lousy father anyway.

The Snyders made good on their offers to help raise the kid, but Naomi’s hand to God, they were morons, and she ended up living with her sister in a half-decent two-bedroom in a new development called Pine Valley, which had nary a pine tree nor a valley within its borders. But the apartment was clean, and things were okay. Naomi had gotten used to radical changes in her domestic situation with her mom, so what she was most comfortable with was something that was safe, temporary, and had an uncertain future. Boxes checked on all that. She’d started a job and classes at the community college once Sarah was old enough for day care, and if she played it all just right, she could be done with veterinary school in another six and a half years.

The most painful part of all of it was the part she never told anyone. Naomi Williams didn’t like her child. Yes, she adored her. Yes, she felt a deep and uncompromising love for her. But in moments when Naomi was honest with herself, she would silently admit that she didn’t really like her kid. Sarah could be the most loving child you’d ever met in your entire life, and also the most hateful, angry, and debilitating. For two years after Naomi’s father died of a sudden heart attack at age fifty-three, Sarah, just picking up on the concept of death, had brought up the sensitive issue to her young, grieving mother with the painful consistency of an abscessed tooth. Someone would mention fathers and the kid would say, “But you can’t ever talk to your daddy again, right, Mama?”

Or the subject of parents in general would come up, and Sarah would look at Naomi and say, “You only have one parent now, and your other one won’t ever come back, right, Mama?”

Or, shit, people would just mention that they’d called somebody on the goddamn phone, and the kid would say, “Your daddy won’t ever call you again, will he?”

Everybody would wince and laugh and say, “She’s trying to make sense of death, the poor thing!” but Naomi knew vindictiveness when she saw it. Her own kid didn’t like her, and she guessed that was okay, because it cut both ways. Yeah, yeah, she loved her, but … she didn’t know. Maybe someday. Right now, she just wanted to keep her head down, grab night shifts at the storage place whenever she could, and put a little more money away. Vet school. That was the prize. Both eyes on it at all times.

NAOMI DUMPED THE TRASH IN THE BIG BIN IN THE FAR CORNER OF THE

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: