По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

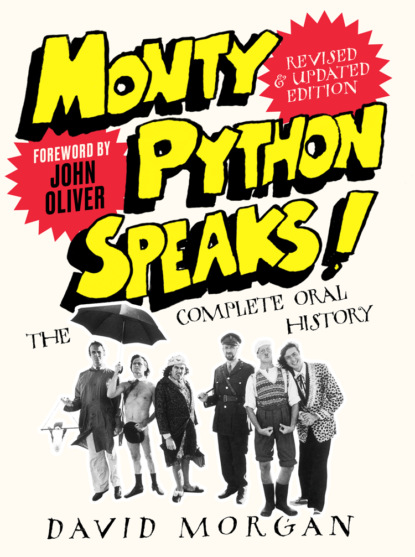

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And the whole thing is so ephemeral, it’s just incredible how thin the line is between being known and not known. There was one day after we’d done a chat show here after one of these series, my wife, Maggie, and I were shopping somewhere, and someone all excitedly started shouting, ‘Hey, hey, look who’s here!’ Oh fuck. It’s this piece of meat that is being attacked by all these excitable people who had just seen you on television the night before. And then you realize, ‘Thank God I’m not John.’ It’s an awful job to walk down the street and be John Cleese, because you can’t escape from it!

CLEESE: You know when you do something and it catches on, and everybody likes it, then for the next eight years as you creep out of your house at half past eight in the morning: ‘Oi, do your funny walk there, John!’ Just so painful!

THE PYTHONS THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (#ulink_a9b3adbb-d920-5d5d-9bc4-e47c99caf76b)

APART FROM THAT HE’S PERFECTLY ALL RIGHT

I asked each of the Pythons what they thought the greatest contributions were of their fellow members to the group, and then to describe how the disparate personalities (sometimes in conflict with one another) merged to become a thriving whole which in many ways was far greater than the sum of its parts.

Cleese, the icon.

THE CONTROL FREAK (#ulink_a9b3adbb-d920-5d5d-9bc4-e47c99caf76b)

It Certainly Wouldn’t Be Worth Your While Risking It Because I’m a Very Good Shot; I Practice Every Day … Well, Not Absolutely Every Day

PALIN: Well, John’s quality, apart from just being very, very focused and disciplined as a writer, was a great economy in his writing – very funny and very tight – and that I think comes from his legal background.

Apart from the superb sense of comic timing – the ability to deliver a line – John was able better than any of us (apart from perhaps Graham) to show this wonderful process of an Establishment character undermining the Establishment. The rest of us could be dismissed as being your sort of irritants, the smaller person getting in the way; or the way our characters were played could sort of be dismissed. [But] the great thing about John’s characters was he epitomized the ruling establishment of Britain; he looked like the bishop or bank manager, a man of authority. He looks just right, and to be able to undermine it as successfully as he did from that perspective was really wonderful and I think the greatest strength of John. It meant that people were really genuinely taken aback when John would be in full blow of invective. His is not just a purely comedic character; this is an archetypal English, respectable, responsible person physically attacking from within. It seemed to me that was an ability that John had, because we all felt he wasn’t acting the part, he was it. That’s the best analogy – he was a headmaster who had gone mad.

John is a very strong, forceful character and within the group he was probably the one who would have the most obsessive desire for structure, both within the sketches and in the way we wrote, the way we worked. John would want to know when we were going to finish, what time we were going to do this, how we were going to do that. We needed that structure, so that was good, as it gave the others who were perhaps more languid something to react against.

As well as having a great time, you had to be businesslike. Not that we were unfocused, but for instance the rest of us were far more likely to say, ‘Let’s stop now and go out and have a nice lunch.’ And John would have to meet somebody, he’d go out and do that and be back at exactly 2:15. So in a sense John forced us to organize ourselves pretty thoroughly, which I think was a good thing, but it didn’t impinge on the comedy. There was never a sort of feeling of, ‘God, here he is, Mr Bossy Boots.’ I mean, he was bossy, but he delivered.

GILLIAM: John’s a hard one. John loves manipulating and controlling; he’s only comfortable when he’s doing that. When he lets go of control and just starts hanging out, he can only do it for a short while and then the panic sets in, it really sets in. I mean, after we did Holy Grail we were in Amsterdam all together promoting it, and we went on a pub crawl one night, and we were having a great time, all of us. And we were getting drunk and speaking openly, all the things that a group can never [otherwise do], and it really was getting funny, and we were saying a lot of things that needed to be said in a really jolly, drunken way. And at a certain point John just had to pull back from it; he was relaxing, he was letting down his guard too much, and he went back off wherever he went. It was really weird. And it was a pity because we were having a good time, and John was having a good time, and he couldn’t allow himself to not try to be in control.

After the first series, John had taken a house down in Majorca, and said, ‘Come on down.’ There was one night we went into Palma and we were sitting there having this silly time, like two guys – ‘Yours isn’t so good looking,’ you know, like two kids laughing, trying to pick up girls and failing miserably and all that – and we were driving back and the sun was setting, and there was this castle on the hill. I said, ‘Oh, shit, let’s drive up there!’ VVrrmm!! Knocked on the door of the castle, it was locked, it was after hours. I said, ‘Let’s break in, let’s climb in.’ So we went around, climbed over the wall and eventually got in. There were sheep grazing in the middle of this castle and we chased them around, it was like really, really good fun – and then John closed down again. It was like one of the few times I’ve seen him just totally relaxed. But he can only do it for a limited period, and then he’s got to get back in control.

I think his attempt to try and control things gave a sense there was always something one could go against – his need to control [versus] our need to not be controlled, and that’s such an interesting dynamic. I don’t know if that’s exactly the best use of everybody in the group!

But John, as I said, was the one we could all struggle against all the time, one thing we always agreed on: ‘He’s going to try this.’ ‘Oh, fuck him!’

Did he serve as a substitute for the BBC,

or a potential audience, that you had to win over?

GILLIAM: No, it wasn’t about that he represented anything larger than himself, or that he was right or wrong. It was about him trying to get his own way. And that’s why he and Terry were at opposite ends, they both wanted their own way. They were these two poles, sort of psychic emotional poles that were at opposite ends – Terry’s passion and John’s intellectual need to control – and that set up this really weird and interesting dynamic.

JONES: When we first started I remember John saying, ‘We don’t want to have personalities in this group, it’s going to be the group.’ Which is why we didn’t sort of have our names and faces up at the end of the show. It was a group undertaking, and that very much came from John’s feeling, I don’t know quite why. He had just come out of At Last the 1948 Show, where somehow Marty Feldman had been perceived to be the star, and Marty had gone on to do his own series, and it was somehow some sort of reaction, against the cult of the individual kind of thing. But nonetheless I think the original offer was from the BBC to John to do a show, and then he came to us and it sort of grew up around him like that.

John was useful to have as your front man; he could deal with the bureaucracy, though there wasn’t that much bureaucracy in those days. John’s contribution was always being kind of a rallying point, a spokesperson. He always had the authority; when it came to dealing with the BBC, we always felt they took John seriously. Partly because he was best known; it’s partly his personality as well. Everybody always feels that John’s really the prime minister in disguise.

Colin ‘Bomber’ Harris wrestling Colin ‘Bomber’ Harris, from Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl.

SPLUNGE! (#ulink_47728b34-88fc-5bef-ba34-02bcfcb237f1)

I’d Like to Answer This Question If I May in Two Ways: Firstly in My Normal Voice and Then in a Kind of Silly, High-Pitched Whine

JONES: I always loved Graham as a performer, from when I first saw him in Cambridge Circus and then in At Last the 1948 Show, because you could never quite see what he was doing. I mean, John I dearly love as a performer, but from the moment you first see John you know where John is; Graham was always very intangible.

I think Graham always played everything as if he didn’t think anything was funny, [as if] he didn’t see the joke in anything, really, which was just wonderful. Which was why he worked for the leads in Holy Grail and Life of Brian, because he played it so straight and sincerely and seriously.

PALIN: The characters that Graham played were again great Establishment characters. He would play a colonel exactly right and add this wonderful mad streak throughout. I think Graham took more risks than John, and I think when they wrote together, although John I’m sure put together 80 per cent of their sketches, the 20 per cent that Graham put in was the truly surreal and extraordinary. Graham had a wonderful gift with words; I’m sure ‘Norwegian Blue’ for a parrot would be Graham’s. There’s something about it: a Norwegian Blue parrot – that just sounds like Graham.

Graham as a performer had a quiet intensity which, if you look at all of his performances, quite unlike any of the rest of us, is very convincing whatever he does. That’s why he was so good as Brian, so good as Arthur; here was a man who genuinely suffered, you know, trying to get through this world – he just happened to be a king, it wasn’t his fault – he was trying to do his best, and all these people around him were just mucking him up. One really felt for him. Graham could portray that very well, partly because I think he was a little nervous as a performer, because he took to drink at one time. By Life of Brian he had given it up, and he didn’t need that, but he was always slightly nervous about it. There’s a concentration in the way Graham does things which looks good, it comes across as very natural and very right.

CLEESE: Graham was fundamentally a very, very fine actor. He could do very odd things, like mime, and he did a very funny impression of the noise made by an espresso machine, things like that. He was a really, really good actor. But to understand Graham you have to realize he didn’t really work properly. If he was a little machine, you would take him back and somebody would fiddle with it, and then it would come back working properly. So he was a very odd man; he was in many ways highly intelligent and quite insightful, in other ways he was a complete child, and not someone who was really any good at taking any sort of responsibility and discharging it.

His best function, and the reason that I wrote with him all those years, is that we got on pretty well. We laughed at the same things, we made each other laugh. And he was the greatest sounding board that I ever worked with. When Graham laughed or thought something funny, he was nearly always right, and that’s extraordinary. For example: when we were writing the ‘Cheese Shop’ [sketch], I kept saying to him, ‘Is this funny? Is this funny?’ And he’d go, [puff puff on his pipe] ‘It’s funny, go on.’ And that’s really how the ‘Cheese Shop’ [sketch] was written as opposed to just being abandoned, because I kept having my doubts. He was a wonderful sounding-board.

And the other side of that was that he was very disorganized – I mean we were all a bit disorganized, but he was really disorganized, and really fundamentally very lazy. His input was minimal; I remember working with Kevin Billington on a movie that turned out to be called The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer. After a couple of sessions, Kevin said to me very quietly, perhaps on a lunch break when Graham had gone to the bathroom, ‘Does Graham usually make so little contribution?’ And I remember being quite surprised by the question, because I’d got used to the fact that he made so little contribution.

He didn’t say very much, but when he did say something it was often very good. But he was never the engine; someone had to be in the engine room driving something forward, and then Graham would sit there and add the new thought or twist here or there, which is terribly useful. But I remember saying to somebody once that there were two kinds of days with Graham; there were the days when I did 80 per cent of the work, and there were the days when he did 5 per cent of the work.

To give you a real example of how bad it could be: when we finished the first series of The Frost Report in 1966, David Frost gave us £1,000 to write a movie script. With the money we went off to Ibiza, and we took a villa for two months and decided to write there, and a whole lot of friends came and stayed with us and passed through, and that is when Graham met David Sherlock. I remember that I would sit inside at the desk writing, and Graham would literally be lying on the balcony outside sunbathing, calling suggestions into the room as I sat there writing.

And the funny thing is I don’t remember being cross about it; I think I just accepted that writing with Graham I was going to have to do 80 per cent of the work and sometimes more. And it always slightly annoyed me when people used to come up to me on Fawlty Towers and say, ‘Well, how much did Connie Booth actually write?’ And I wanted to say to them, ‘Certainly a lot more than Graham ever wrote.’ That used to annoy me, the assumption that because Graham was a man he was obviously making a bigger contribution than Connie as a woman.

SHERLOCK: Graham would have been a very good shrink, because if nothing else he understood what made people tick. And if he couldn’t understand, he would make it his job to find out. And his interview technique, if he was looking for prospective interesting people wanting to join his coterie, within five minutes he could sum somebody up and sort them out.

However, I think he was far less astute financially than Cleese, who had a great many friends who were accountants – hence a lot of the sketches! – but he learned from them. Sadly those sort of people bored Graham, I don’t think he was even interested [in connecting]. That’s why he lost money while others were gaining.

One of the most delightful sounds I’ve ever heard was Graham and John writing. This was in the days when we lived in Highgate in the Seventies. I would often be preparing food for our large nuclear family (who could be anything from three to four to ten on an evening sometimes, depending on who Graham invited back from the pub or whatever). Part of my life consisted of keeping the household kicking over. I didn’t do it very well, but it was fairly Bohemian anyway, so it didn’t matter too much. But in the morning if I was making coffee for them, I would often hear a delighted shriek as they hit on some outrageous idea, often followed by the thudding of bodies hitting the floor, and the drumming of feet like a child with a tantrum, only this was the sheer delight of the idiocy

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: