Congo

Ninety thousand years of human history, ninety thousand years of society … such vitality! No timeless state of nature occupied by noble savages or bloodthirsty barbarians. It was what it was: history, movement, attempts to contain the misery, attempts that sometimes brought new misery, for the dream and the shadow are the closest of friends. There had never been anything like standing still; the major changes followed each other with ever-increasing momentum. As history moved faster, the horizon expanded. Hunter-gatherers had lived in groups of perhaps fifty individuals, but the earliest farmers already had communities of five hundred. When those societies expanded to become organized states, the individual was absorbed into contexts of thousands or even tens of thousands of people. At its zenith, the Kongo Empire had as many as five hundred thousand subjects. But the slave trade annihilated those broader ties. And in the rain forest, far from the river, people still lived in small, closed societies. Even in 1870.

IN MARCH 2010, as I was putting the finishing touches to this manuscript, I booked a flight to Kinshasa. I wanted to visit Nkasi again, this time accompanied by a cameraman. I resolved to take him a nice silk shirt, for poverty cannot be combated with powdered milk alone. Regularly, during the long months of work on this book, I had called his nephew to ask how Nkasi was getting along. “Il se porte toujours bien!” (He’s still doing fine) was always the cheerful announcement from the other end. Less than one week before my deadline, five days before my departure, I called again. That was when I heard that he had just died. His family had left Kinshasa with the body, to bury him at Ntimansi, the village in Bas-Congo where he had been born an eternity ago.

I looked out the window. Brussels was going through the final days of a winter that knew no respite. And as I stood there like that, I could not help thinking about the bananas he had slid over to me during our first meeting. “Take it, eat.” Such a warm gesture, in a country that makes the news so much more often for its corruption than for its generosity.

And I had to think about that afternoon in December 2008. After a long talk Nkasi had needed a rest, and I entered into conversation with Marcel, one of his great-nephews. We were sitting in the courtyard. Long lines of wash had been hung out to dry and a few women were sorting dried beans. Marcel was wearing a baseball cap with the visor turned to the back and was leaning back comfortably in a plastic garden chair. He started talking about his life. Although he had been good at school, he had now been relegated to the marché ambulant (walking marketplace). He was one of the thousands and thousands of young people who spent all day crossing the city with a few articles to sell—a pair of trousers, two baskets, four belts, a map. Sometimes he would sell only two baskets a day, a turnover of less than four dollars. Marcel sighed. “All I want is for my three children to be able to go to school,” he said. “I liked school so much myself, especially literature.” And to prove that, in a deep voice he began reciting “Le soufflé des ancêtres,” the long poem by the Senegalese poet Birago Diop. He knew great chunks of it by heart.

Listen more often

To things rather than people

You can hear the voice of the fire,

Hear too the voice of the water.

Listen to the bush

Sobbing in the wind:

It is the breath of the dead.

Those who died never went away:

They are in the shadow that lights up

And also in the shadow that folds in upon itself.

The dead are not beneath the ground:

They are in the leaves that rustle,

They are in the wood that groans,

They are in the water that rushes,

They are in the water at rest,

They are with the people, they are in the hut.

The dead are not dead.15

Winter on the rooftops of Brussels. The news I just received. His voice that I can still hear. “Take it, eat.”

CHAPTER 1

NEW SPIRITS

Central Africa Draws the Attention of East and West

1870–1885

NO ONE KNOWS EXACTLY WHEN DISASI MAKULO WAS BORN. But then neither did he. “I was born in the days when the white man had still not arrived in our area,” he told his children many years later. “We didn’t know then that there were people in the world with skin of a different color.”1 It must have been around 1870–72. He died in 1941. Not long before, he had dictated his life’s story to one of his sons. It would appear in print only in the 1980s; twice in fact, in Kinshasa and again in Kisangani, but Zaïre, as Congo was called in those days, was as good as bankrupt. The publications were sober, with limited print runs and distribution. And that is unfortunate, because the life story of Disasi Makulo is above all a fantastic adventure. To understand the last quarter of the nineteenth century in Central Africa there is no better guide than Makulo.

Where Disasi was born, however, he knew very well: in the village of Bandio. He was the son of Asalo and Boheheli, a Turumbu tribesman. Bandio lay in the district of Basoko, now Orientale province. The heart of the equatorial forest, in other words. Aboard the boat from Kinshasa to Kisangani, a few weeks’ journey upstream along the Congo, one passes on the port side a few days before arrival the large village of Basoko. It is on the northern bank, at the confluence with the Aruwimi, one of the Congo’s larger tributaries. Bandio is to the east of Basoko, a ways back from the river itself.

His parents were not fishing folk; they lived in the jungle. His mother raised manioc. With her hoe or digging tool she would chop at the earth to pry loose the thick tubers. She lined them up to dry in the sun and, a few days later, ground them to flour. His father worked with palm oil. Climbing high into the trees with his machete, he chopped off the bunches of greasy nuts. Then he would press them until the lovely juice ran out, a deep orange, a sort of liquid copper that has added to the region’s wealth since time immemorial. That palm oil could be used to trade with the fishermen along the river. Commercial ties had existed for centuries between the riverine inhabitants, who had fish in abundance, and the people of the forest with their surpluses of palm oil, manioc, or plantains. The result was a balanced diet: the protein-rich fish was taken to the rain forest, the starchy crops and vegetable oil were left on the banks.

Bandio was a relatively insular world. The radius of activity covered in a human lifetime was limited to a few dozen kilometers. People sometimes visited another village to attend a wedding or arrange an inheritance, but most of them left their region seldom or never. They died where they were born. When Disasi Makulo entered the world with a shriek, the villagers of Bandio knew nothing of the outside world. They knew nothing of the permanent presence of the Portuguese a thousand kilometers to the west, along the Atlantic, nor in fact of the existence of an ocean. The Portuguese colony of Angola had lost much of its splendor, as had Portugal itself, but—for Africans as well—Portuguese remained the major trading language along the coast south of the mouth of the Congo. Nor did Disasi’s people know that, since the eighteenth century, the British had taken over the trade of the Portuguese along the Congo’s lower reaches and embouchure. That the Dutch and the French had settled there as well: they could never have guessed that, for none of those Europeans ever made their way inland. They remained on the coast and the area immediately behind it, waiting till the caravans led by African traders reached them with their goods from the interior: ivory in particular, but also palm oil, peanuts, coffee, baobab bark, and pigments such as orchil and copal. Not to mention slaves. Although the trade in human beings had been abolished throughout the Western world in those years, it went on in secret for quite some time. The Westerners paid with precious cloth, bits of copper, gunpowder, muskets, and red or blue pearls or rare seashells. This latter commodity was no act of clever Western fraud. As with official coinage, those shells were piece goods of great value that could be transported easily and were impossible to counterfeit. But Bandio was too far away to see much of that. If such a white, gleaming shell or bead necklace actually happened to make it to their area, no one knew exactly where it came from.

Newborn Disasi’s fellow villagers may have known nothing about the Europeans on the west coast, but they were even less informed about the great upheavals taking place more than a thousand kilometers to the east and north. Beginning in 1850, the Central African rainforest had also attracted the attention of merchants from the island of Zanzibar, as well as from the African east coast (present-day Tanzania) and even from two thousand kilometers away in Egypt. Their interest was prompted by a natural raw material that had been valued around the world for centuries as a luxury good for the manufacture of princely Chinese tablets, Indian figurines, and medieval reliquaries. That material was ivory. High-grade ivory was found in huge quantities in the African interior. The tusks of the African elephant comprised the largest and purest pieces of ivory in the world, weighing up to seventy kilos and more. Unlike the Asian elephant, already rare by that time, the female of the African species bore tusks as well. In the mid-nineteenth century this seemingly inexhaustible treasure trove was the subject of increasingly close perusal.

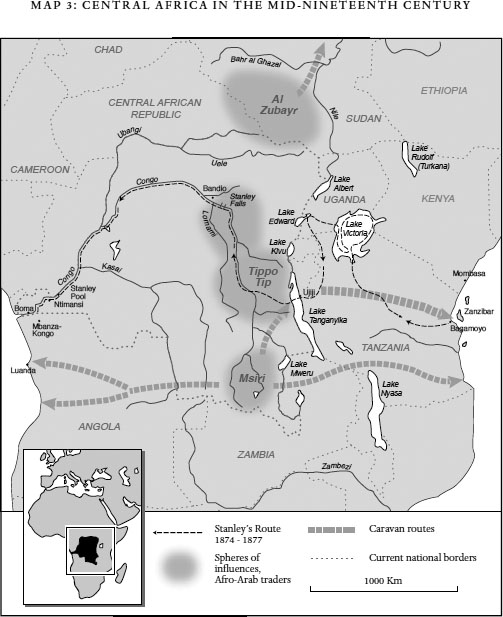

In the northeast of what would later become Congo, where the rain forest meets the savanna, traders from the Nile Valley were active: Sudanese, Nubians, and even Egyptian Copts. Their clientele lived as far away as Cairo. The traders traveled to the south by way of Darfur or Khartoum. Slaves and ivory were the major export products, razzias and hunting parties the principle form of acquisition. By 1856 the entire trade had gradually entered the hands of a single individual: al-Zubayr, a powerful trader whose empire in 1880 extended from Northern Congo to Darfur. Officially, his trading zone was a province of Egypt; in practice, it comprised an empire unto itself. The Arab influence spread all the way to southern Sudan.

But it was above all Zanzibar, an unsightly island in the Indian Ocean off the coast of present-day Tanzania, that played a crucial role. When the sultan of Oman settled there in 1832 to control the flow of trade in the Indian Ocean, the move had far-reaching consequences for all of eastern Africa. Zanzibar, itself rich only in coconuts and cloves, became the global transfer table for slaves. The island exported to the Arabian Peninsula, the Mideast, the Indian subcontinent, and China.

In 1870 the villagers of Bandio noticed none of this. But the Zanzibar traders possessed excellent firearms and so they themselves moved farther and farther into the interior, farther than the Europeans to the west ever had. Some of them were pure Arabs, others were of mixed African blood. Often they included African converts to Islam, whom we refer to as Afro-Arab or Swahilo-Arab traders; in the nineteenth century, however, they were called les arabisés. Swahili, a Bantu language with many Arabic loan words, spread all over Eastern Africa. Starting at Zanzibar and the town of Bagamoyo on the coast, huge caravans began heading inland from 1850 on, until they reached the shores of Lake Tanganyika, eight hundred kilometers to the west. The settlement of Ujiji, where Stanley would “find” Livingstone in 1871, became a major trading post. From the lake’s far shore the caravans moved even farther inland, into the area now known as Congo. As with the trading empire of al-Zubayr, one saw spheres of commercial influence solidify into political entities. In southeastern Katanga, Msiri, a trader from the African east coast, took over an existing realm: the ancient, but by-then mordant Lunda Empire. From 1856 to 1891 he was lord and master over this region rich in copper and controlled all trade routes to the east. His interests, at first purely commercial, in this way took on political form.

A bit farther to the north, the notorious ivory and slave trader Tippo Tip reigned supreme. As son of an Afro-Arab family from Zanzibar he answered directly to the Sultan, but soon he became the most powerful man in all of eastern Congo. His authority was felt in the area that stretched between the Great Lakes to the east and the headwaters of the Congo (also referred to there as Lualaba), three hundred kilometers (185 miles) to the west. Tippo Tip’s power was founded not only on his exceptional business sense, but also on violence. At first he had acquired his luxury goods—slaves and ivory—in a friendly fashion: like other Zanzibaris, he established pacts with local leaders for the purposes of bartering. A number of those leaders became vassals of the Afro-Arab traders. Yet, from 1870 on, all that changed. As more and more tons of ivory began flowing eastward, traders like Tippo Tip grew in power and wealth. In the final account, the sacking and pillaging of entire villages proved more cost effective than bartering for a few tusks and adolescents. Why spend days chattering with the local village chieftain, refusing lukewarm palm wine that your religion forbade you to drink anyway, when you could just as easily torch his village? In addition to ivory, this new approach also produced additional slaves to carry that ivory. Raiding became more important than trading; firearms tipped the scales. The name Tippo Tip sent shivers down the spines of those inhabiting an area half the size of Europe. In fact, it wasn’t even his real name (that was Hamed ben Mohammed al-Murjebi), but probably an onomatopoeiac form derived from the sound of his rifle.

At Disasi Makulo’s home in Bandio, however, no one had ever heard of Tippo Tip. The stage was still empty, the world still a verdant green. In the wings, to the left and right, foreign traders—European Christians and Afro-Arab Muslims—stood awaiting their cues, ready to push on into the heart of Central Africa. It was only because the region’s power structures were already in a wretched state, due in part to the European slave trade carried out in the centuries before, that their offensive was even possible. Not much was left in those days of the once so-powerful native kingdoms, and social structures in the jungle had always been less complex than those on the savanna. The political vacuum in the interior, therefore, offered new economic opportunities for foreigners. That is putting it nicely. In reality, the period to come was one of administrative anarchy, rapaciousness, and violence. But not yet. Little Disasi still lay slumbering, tied to his mother’s back, his cheek pressed to her shoulder blade. The wind rustled in the treetops. After a thunderstorm, the rain forest went on dripping for hours.

“ONE DAY, a few people from the riverside came to visit my parents.” Thus begins Disasi Makulo’s earliest recollection. He must have been five or six at the time. The strangers brought with them a very peculiar story. “They said they had seen something bizarre on the river, a spirit perhaps. ‘We saw a huge, mysterious canoe,’ they said, ‘that rowed itself. In that canoe is a man, white from head to toe, like an albino, covered completely in garments, you could see only his head and his arms. He had a few black men with him.’”2

Besides fish and palm oil, the peoples of the river and the jungle also traded information. The river people, of course, had a tendency to come up with weird news anyway—you could hardly imagine the crazy things they heard from fishermen and traders further along!—but this report sounded particularly strange. What’s more, it was no secondhand account. The clothed albino they had seen was no one less than Henry Morton Stanley. The little group of black men were his bearers and helpers from Zanzibar. That huge, mysterious canoe was the Lady Alice, his eight-meter-long steel boat. After he had found the presumably lost physician, missionary, and explorer David Livingstone on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in 1871, the New York Herald and the Daily Telegraph of London had commissioned Stanley to carry out, from 1874 to 1877, what would become the mother of all exploratory expeditions: the crossing of Central Africa from east to west, a staggering journey through festering swamps, hostile tribal territories, and murderous rapids.

It was around the middle of that same century that Europe had come down with the fever of discovery. Newspapers and geographical societies challenged adventurers to explore mountain ranges, chart rivers, and map jungles. A sort of mythical fascination arose for “the sources” of streams and rivers, in particular that of the Nile. Shortly before his meeting with Stanley, the Scotsman Livingstone had found the Lualaba, a broad but unnavigable river in eastern Congo that flowed north, and which he thought could very well constitute the headwaters of the Nile. In 1875 the Englishman Lovett Cameron stood on the banks of that same river. Cameron, however, realized that a bend to the west later on was all it would take to make this, in fact, the Congo, the mouth of which was already known thousands of kilometers away on the Atlantic coast. Neither of them succeeded in following that river. Stanley did.

He left Zanzibar with his caravan in 1874 and, just to be sure, took his own ship along with him. The Lady Alice could be taken apart and portaged like a set of Tinker Toys. What a strange sight that must have been: a long caravan threading its way across the boiling hot savanna of Eastern Africa, hundreds of kilometers from any navigable current, with at the back a group of twenty-four porters bearing the man-size, glistening sections of an otherworldly steel hull.

Stanley subjected Lake Victoria and Lake Tanganyika to a very close inspection. Then, setting out to the west in 1876, he entered the territory of the much-feared but, upon closer acquaintance, also gallant Tippo Tip, with whom he made a deal. In return for a generous reward, Tippo Tip and his men would accompany Stanley a long way to the north along the Lualaba. It was what we today might call a “win-win” situation: Stanley was protected by Tippo Tip, and Tippo Tip could expand into the new territories he discovered along with Stanley.

It worked, although the presence in Stanley’s entourage of the most notorious slave driver of all did generate great hostility among the local population. No one knew what an explorer was; Stanley was seen as just another trader. Spears and poisoned arrows came raining down on more than one occasion, and more than once, there were casualties. Although in his writings Stanley tended to exaggerate the number of such clashes (which did his reputation no good), their frequency indicates how much the Arab slave trade had disrupted the area. After passing a series of cataracts, the river became navigable and turned off to the west. Stanley named the spot Stanley Falls (later Stanleyville, today’s Kisangani). Bidding farewell to Tippo Tip and accompanied by several native canoes, he moved on alone into the area where no European or Afro-Arab trader had ever been before.

On February 1, 1877, at two in the afternoon, his ship passed the area where the friends of Disasi Makulo’s parents lived. Drums had warned the inhabitants along the banks of his approach, and they had prepared themselves well.3 A war party of forty-five large dugouts carrying a hundred men each headed for Stanley’s little flotilla. He noted: “In these savage areas our mere presence awakens the most furious passions of hatred and murder, as a low-lying ship in shallow water stirs up muddy sediment.” It was, indeed, one of the most impressive military confrontations on his journey. Hundreds of sinewy arms paddled in unison. The canoes approached the Lady Alice on waves of foam. At their bows, warriors with colorful feather headdresses were standing ready with their spears. At the stern sat the village elders. There was a deafening sound of drums and horns. “This is a bloodthirsty world,” Stanley wrote, “and for the first time we feel that we hate the filthy, rapacious ghouls who live here.”4 As soon as the first cloud of spears came raining down, musket fire rang out. Stanley shot his way to shore. Once on land he found piles of tusks, and in the villages he saw human skulls mounted on poles. By five that afternoon he was gone.

It seemed like a one-off incident, a terrible apparition, an inexplicable epiphany. Peace and quiet returned, or at least so the villagers thought. But that afternoon passage would change their lives, and especially that of Disasi Makulo.

One week later, for the umpteenth time, Stanley asked a native what this river was called. For the first time he was told: “Ikuti ya Congo” (This is the Congo).5 A simple answer, but one which filled him with joy: now he knew for sure that he would not end up at the pyramids of Giza, but at the Atlantic. He soon began seeing the first Portuguese muskets as well. The attacks from the riverbanks tapered off, but malnutrition, heat, illness, fever, and rapids continued to take their toll on this historic crossing of Central Africa.

On August 9, 1877, more than six months after passing through Disasi’s homeland, to the extreme west of that vast area, near the sleepy trading post of Boma close to the Atlantic, an exhausted and emaciated white man dropped his things. No one knew that this bundle of starvation and misery was the first European to have followed the entire course of the Congo. Of the four white men who had left the east coast with him, Stanley was the only one who survived. Of the 224 members of the expedition, only ninety-two reached the west coast of Africa. It was a heroic journey, and one with far-reaching consequences: within the space of three years, from 1874 to 1877, Stanley had circumnavigated and mapped two gigantic lakes, Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria; he had unraveled the complex hydrology of the Nile and the Congo and charted the watersheds of Africa’s two largest rivers; and he had carefully documented the course of the Congo and blazed a trail through equatorial Africa.6 The world would never be the same. Today, Stanley’s name is associated sooner with that one, awkward sentence—“Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”—with which he tried to maintain Victorian decorum in the tropics, than with his much more impressive achievement, which would change forever the lives of hundreds of thousands in Central Africa.

THE PEOPLE in Disasi Makulo’s region thought they had seen a ghost. How could they know that many thousands of kilometers to the north there was a cold and rainy continent where, in the course of the last century, something as mundane as boiling water had changed history? They knew nothing of the industrial revolution that had altered the face of Europe. The existence of a society, largely agrarian as their own, which had suddenly acquired coal mines, smokestacks, stream locomotives, suburbs, incandescent lighting, and socialists, was beyond their ken. In Europe it was raining inventions and discoveries, but none of that had trickled down to Central Africa. It would have taken the large part of an afternoon to explain to them what a train was.

The forest inhabitants could not have dreamed that the industrialization set in motion by the power of steam would change not only Europe, but the whole world. More industry meant greater production, more goods, and so more competition for markets and natural resources. The circles within which a European factory did its buying and selling were expanding all the time. Regional became national, national became global. World trade was growing like never before. Around 1885 steamships replaced sailing ships on the long-distance routes. The tea drunk by a rich Liverpool family came from Ceylon. In Worcester, a sauce was made on an industrial scale using ingredients from India. Dutch ships carried printing presses to Java. And in South Africa, special ostriches were being raised so that women in Paris, London, and New York could wear large, bobbing feathers on their bonnets. The world was growing smaller and smaller, time was going faster and faster. And the nervous heartbeat of this new era could be heard everywhere in offices, train stations and border posts in the hectic tapping of the telegraph.