По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

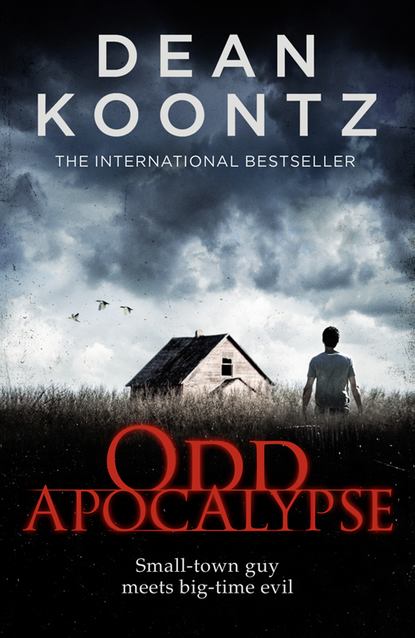

Odd Apocalypse

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Kenny stared at me as if I had suddenly begun speaking in a foreign language. A foreign language, the sound of which offended him so much that he might shoot me just to shut me up.

To change the subject, I put one finger to my upper lip, at the same spot at which a cold sore blazed on Kenny’s lip. “That’s got to hurt.”

I didn’t think he could bristle any further, but he seemed to swell with umbrage. “You saying I’m diseased?”

“No. Not at all. You look as healthy as a bull. Any bull should be happy to be as healthy as you. I’m just saying that one little thing you’ve got there, it must hurt.”

His quills relaxed a little. “Hurts like a sonofabitch.”

“What’re you doing for it?”

“Nothing you can do for a sonofabitch canker. Sonofabitch has to heal itself.”

“That’s not a canker. It’s a cold sore.”

“Everybody says it’s a canker.”

“Cankers are inside the mouth. They look different. How long have you had it?”

“Been six days. Sonofabitch makes me want to scream sometimes.”

I winced to express sympathy. “Before you got it, was there a tingling in your lip, just where it eventually showed up?”

“That’s exactly right,” Kenny said, his eyes widening as if I had proven to be clairvoyant. “A tingle.”

Casually pushing the barrel of the Uzi away from me, I said, “Within twenty-four hours before the tingle, were you out in very hot sun or cold wind?”

“Wind. Week before last, we had a cold snap. Blew in from the northwest like a sonofabitch.”

“You got a little windburn. Too much hot sun or a cold wind can trigger a sore like that. Now that you’ve got it, dab just a little Vaseline on it and stay out of the sun, out of the wind. If you stop irritating the thing, it’ll close up fast enough.”

Kenny touched his tongue to the sore, saw that I disapproved, and said, “You some kind of doctor?”

“No, but I’ve known a couple doctors pretty well. You’re on the security team, I guess.”

“Do I look like I’m the entertainment director?”

I took a chance that we had bonded enough for me to laugh warmly and say, “I suspect you’d be entertaining as hell over a few beers.”

Full of crooked dark-yellow teeth, his cold-sore grin was as appealing as a possum run down by an eighteen-wheeler. “Everybody says old Kenny’s a hoot when you pour some beers in him. Only problem is, after about ten of ’em, I stop feeling hilarious and start tearing things up.”

“Me too,” I claimed, though I’d never had more than two beers in the same day. “But I have to say, with some regret, I doubt that I can do such a handsome amount of damage to a place as you can.”

I had plucked a perfect note from his pride.

“I have committed some memorable ruination, for sure,” he said, and his fearsome facial scars grew a brighter red, as if the memory of past rampages raised the temperature of his self-esteem.

Gradually I had become aware that the quality of light in the stable was changing. Now I glanced to my right and saw that the eastern windows were still aglow with sunlight made ruddy by the coppery tint of the glass, but were not as bright as they had been.

Pointing the Uzi at the floor or perhaps at my feet, Kenny said, “So, kid, what’s your name?”

I tensed a little and returned my attention fully to the giant, whom I had by no means yet won over.

“Listen,” I said, “don’t think I’m shining you on or anything, this really is my name, strange as it might sound. My name is Odd. Odd Thomas.”

“Nothing wrong with the Thomas part.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“And, you know, Odd isn’t as bad as some things parents do to kids. Parents can wreck you, man. My parents were the nastiest—”

To complete Kenny’s observation of his parents as he made it, conjure in your mind several words, never spoken in polite company, that suggest incest, self-gratification, gross violations of laws protecting animals from the perverse desires of human beings, erotic obsession with the product of a major cereal company, and the most bizarre use of the tongue that you can imagine. …

On second thought, forget it. Kenny’s characterization of his parents was unique in the colorful history of gutter speech. No matter how long you pondered the puzzle I’ve set before you, your solution would be the palest approximation of what he said.

Then he continued: “My born last name is Keister. You know what Keister means?”

Although we seemed to be laying the foundations of a friendship, I suspected that I could go from Kenny’s A-list to his death list from one second to the next. I was concerned that acknowledging my awareness of the meaning of the word Keister might light his fuse.

But he had asked. So I said, “Well, sir, it’s slang, and some people use it to mean a person’s bottom, you know, like what you sit on, you know, like the seat of your pants, or even sometimes, well, buttocks.”

“Ass,” he declared, managing to hiss and growl the word at the same time, while thundering it out loud enough to rattle the stable windows. “Keister means ass.”

I dared to glance to my left, and I saw that the western windows admitted more and much ruddier light than had shone through them only a few minutes earlier.

“You know what my first name was, my born name?” Kenny asked, though in such a way as to make the question a demand.

Meeting his gaze again and finding it no less disturbing, I said, “I guess it wasn’t Kenny.”

He closed his eyes and took a deep breath, his face squinched as if he must be preparing himself for a difficult revelation.

For an instant I considered bolting for the nearer door, but I was afraid that by trying to flee I would put the lie to my pretense of friendship, motivating the forsaken Kenny to shoot me in the back.

Although they were to one degree or another eccentric, everyone else at Roseland tried to maintain an air of normalcy. This colorful giant, this walking armory with screaming-hyena tattoos snarling on his massive arms, made no such effort. I found it all but impossible to see him working with the other members of the estate-security team whom I had met. The safest assumption was that he was not a Roseland guard and not to be trusted for a second.

He took another deep breath, blew it out, opened his eyes, and said, “My born first name was Jack. They named me Jack Keister.”

“That’s just cruel, sir.”

“Sonofabitch bastards,” he said, which I inferred to be a less infuriated reference to his parents. “I got teased from day one in preschool, the little sonsofbitches couldn’t even wait till first grade. Minute I turned eighteen, I went to court to change my name.”

I almost said To Kenny Keister? but fortunately held my tongue.

“Kenneth Randolph Fitzgerald Mountbatten,” he said, rolling the names across his tongue with all the authority of the finest British stage actor.

“Impressive,” I declared, “and may I say, exactly fitting.”

He almost blushed with pleasure. “They’re names I always liked, so I strung ’em together.”