По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

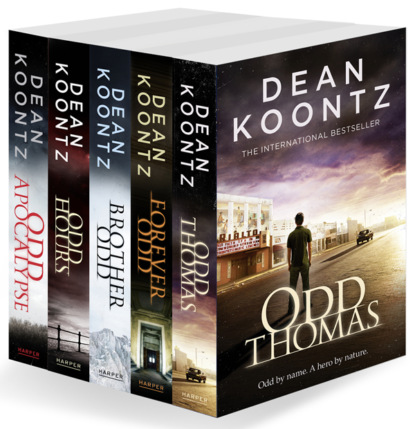

Odd Thomas Series Books 1-5

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“May.”

“What day?”

I picked one at random: “The twenty-ninth.”

“That was a Wednesday,” Terri said.

The lunch rush had passed. My workday had ended at two o’clock. We were in a booth at the back of the Grille, waiting for a second-shift waitress, Viola Peabody, to bring our lunch.

I had been relieved at the short-order station by Poke Barnet. Thirty-some years older than I am, lean and sinewy, Poke has a Mojave-cured face and gunfighter eyes. He is as silent as a Gila monster sunning on a rock, as self-contained as any cactus.

If Poke had lived a previous life in the Old West, he had more likely been a marshal with a lightning-quick draw, or even one of the Dalton gang, rather than a chuck-wagon cook. With or without past-life experience, however, he was a good man at grill and griddle.

“On Wednesday, May 29, 1963,” Terri said, “Priscilla graduated from Immaculate Conception High School in Memphis.”

“Priscilla Presley?”

“She was Priscilla Beaulieu back then. During the graduation ceremony, Elvis waited in a car outside the school.”

“He wasn’t invited?”

“Sure he was. But his presence in the auditorium would have been a major disruption.”

“When were they married?”

“Too easy. May 1, 1967, shortly before noon, in a suite in the Aladdin Hotel, Las Vegas.”

Terri was fifteen when Elvis died. He wasn’t a heartthrob in those days. By then he had become a bloated caricature of himself in embroidered, rhinestone-spangled jumpsuits more appropriate for Liberace than for the bluesy singer with a hard rhythm edge who had first hit the top of the charts in 1956, with “Heartbreak Hotel.”

Terri hadn’t yet been born in 1956. Her fascination with Presley had not begun until sixteen years after his death.

The origins of this obsession are in part mysterious to her. One reason Elvis mattered, she said, was that in his prime, pop music had still been politically innocent, therefore deeply life-affirming, therefore relevant. By the time he died, most pop songs had become, usually without the conscious intention of those who wrote and sang them, anthems endorsing the values of fascism, which remains the case to this day.

I suspect that Terri is obsessed with Elvis partly because, on an unconscious level, she has been aware that he has moved among us here in Pico Mundo at least since my childhood, perhaps ever since his death, a truth that I revealed to her only a year ago. I suspect she is a latent medium, that she may sense his spiritual presence, and that as a consequence she is powerfully drawn to the study of his life and career.

I have no idea why the King of Rock-’n’-Roll has not moved on to the Other Side but continues, after so many years, to haunt this world. After all, Buddy Holly hasn’t hung around; he’s gotten on with death in the proper fashion.

And why does Elvis linger in Pico Mundo instead of in Memphis or Vegas?

According to Terri, who knows everything there is to know about all the days of Elvis’s busy forty-two years, he never visited our town when he was alive. In all the literature of the paranormal, no mention is made of such a geographically dislocated haunting.

We were puzzling over this mystery, not for the first time, when Viola Peabody brought our late lunch. Viola is as black as Bertie Orbic is round, as thin as Helen Arches is flat-footed.

Depositing our plates on the table, Viola said, “Odd, will you read me?”

More than a few folks in Pico Mundo think that I’m some sort of psychic: perhaps a clairvoyant, a thaumaturge, seer, soothsayer, something. Only a handful know that I see the restless dead. The others have whittled an image of me with the distorting knives of rumor until I am a different piece of scrimshaw to each of them.

“I’ve told you, Viola, I’m not a palmist or a head-bump reader. And tea leaves aren’t anything to me but garbage.”

“So read my face,” she said. “Tell me—do you see what I saw in a dream last night?”

Viola was usually a cheerful person, even though her husband, Rafael, had traded up to a waitress at a fancy steak house over in Arroyo City, thereafter providing neither counsel nor support for their two children. On this occasion, however, Viola appeared solemn as never before, and worried.

I told her, “The last thing I can read is faces.”

Every human face is more enigmatic than the time-worn expression on the famous Sphinx out there in the sands of Egypt.

“In my dream,” Viola said, “I saw myself, and my face was ... broken, dead. I had a hole in my forehead.”

“Maybe it was a dream about why you married Rafael.”

“Not funny,” Terri admonished me.

“I think maybe I’d been shot,” Viola said.

“Honey,” Terri comforted her, “when’s the last time you had a dream come true?”

“I guess never,” Viola said.

“Then I wouldn’t worry about this one.”

“Best I can remember,” Viola said, “I’ve never before seen myself face-on in a dream.”

Even in my nightmares, which sometimes do come true, I’ve never glimpsed my face, either.

“I had a hole in my forehead,” she repeated, “and my face was ... spooky, all out of kilter.”

A high-powered round of significant caliber, upon puncturing the forehead, would release tremendous energy that might distort the structure of the entire skull, resulting in a subtle but disturbing new arrangement of the features.

“My right eye,” Viola added, “was bloodshot and seemed to ... to swell half out of the socket.”

In our dreams, we are not detached observers, as are the characters who dream in movies. These internal dramas are usually seen strictly from the dreamer’s point of view. In nightmares, we can’t look into our own eyes except by indirection, perhaps because we fear discovering that therein lie the worst monsters plaguing us.

Viola’s face, sweet as milk chocolate, was now distorted by a beseeching expression. “Tell me the truth, Odd. Do you see death in me?”

I didn’t say to her that death lies dormant in each of us and will bloom in time.

Although not one small detail of Viola’s future, whether grim or bright, had been revealed to me, the delicious aroma of my untouched cheeseburger induced me to lie in order to get on with lunch: “You’ll live a long happy life and pass away in your sleep, of old age.”

“Really?”

Smiling and nodding, I was unashamed of this deception. For one thing, it might be true. I see no real harm in giving people hope. Besides, I had not sought to be her oracle.

In a better mood than she’d arrived, Viola departed, returning to the paying customers.

Picking up my cheeseburger, I said to Terri, “October 23, 1958.”

“Elvis was in the army then,” she said, hesitating only to chew a bite of her grilled-cheese sandwich. “He was stationed in Germany.”