По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

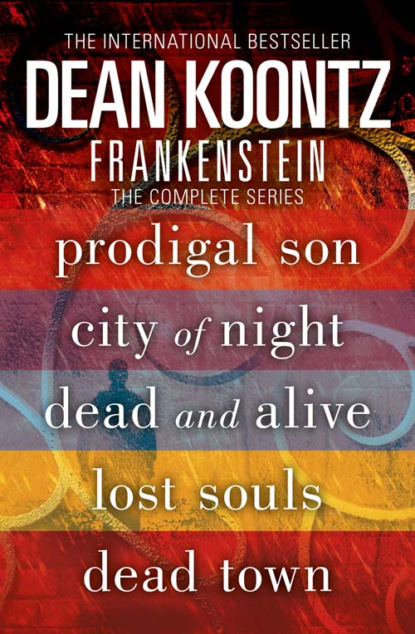

Frankenstein: The Complete 5-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Potbellied, with a hound-dog face full of sags and swags that added years to his true age, Jack Rogers looked older now than he usually did. Although his excitement was palpable, his face had a gray tinge.

“Luke’s got a good eye for physiological anomalies,” Jack said. “He knows his guts.”

Luke nodded, taking pride in his boss’s praise. “I’ve just always been interested in viscera since I was a kid.”

“With me,” Michael said, “it was baseball.”

Jack said, “Luke and I completed every phase of the internal examination. Head, body cavities, neck, respiratory tract—”

“Cardiovascular system,” Luke continued, “gastrointestinal tract, biliary tract, pancreas, spleen, adrenals—”

“Urinary tract, reproductive tract, and musculoskeletal system,” Jack concluded.

The cadaver on the table certainly appeared to have been well explored.

If the body had not been so fresh, Carson would have wanted to grease her nostrils with Vicks. She could tolerate this lesser stench of violated stomach and intestines.

“Every phase revealed such bizarre anatomy,” Jack said, “we’re going back through again to see what we might’ve missed.”

“Bizarre? Such as?”

“He had two hearts.”

“What do you mean two hearts?”

“Two. The number after one, before three. Uno, dos.”

“In other words,” Luke said earnestly, “twice as many as he should have had.”

“We got that part,” Michael assured him. “But at the library, we saw Allwine’s chest open. You could have parked a Volkswagen in there. If everything’s missing, how do you know he had two hearts?”

“For one thing, the associated plumbing,” Jack said. “He had the arteries and veins to serve a double pump. The indicators are numerous. They’ll all be in my final report. But that’s not the only thing weird about Allwine.”

“What else?”

“Skull bone’s as dense as armor. I burnt out two electric trepanning saws trying to cut through it.”

“He had a pair of livers, too,” said Luke, “and a twelve-ounce spleen. The average spleen is seven ounces.”

“A more extensive lymphatic system than you’ll ever see in a textbook,” Jack continued. “Plus two organs – I don’t even know what they are.”

“So he was some kind of freak,” Michael said. “He looked normal on the outside. Maybe not a male model, but not the Elephant Man, either. Inside, he’s all screwed up.”

“Nature is full of freaks,” Luke said. “Snakes with two heads. Frogs with five legs. Siamese twins. You’d be surprised how many people are born with six fingers on one hand or the other. But that’s not like” – he patted Allwine’s bare foot – “our buddy here.”

Having trouble getting her mind around the meaning of all this, Carson said, “So what are the odds of this? Ten million to one?”

Wiping the back of his shirt sleeve across his damp brow, Jack Rogers said, “Get real, O’Connor. Nothing like this is possible, period. This isn’t mutation. This is design.”

For a moment she didn’t know what to say, and perhaps for the first time ever, even Michael was at a loss for words.

Anticipating them, Jack said, “And don’t ask me what I mean by design. Damn if I know.”

“It’s just,” Luke elaborated, “that all these things look like they’re meant to be … improvements.”

Carson said, “The Surgeon’s other victims … you didn’t find anything weird in them?”

“Zip, zero, nada. You read the reports.”

Such an aura of unreality had descended upon the room that Carson wouldn’t have been entirely surprised if the eviscerated cadaver had sat up on the autopsy table and tried to explain itself.

Michael said, “Jack, we’d sure like to embargo your autopsy report on Allwine. File it here but don’t send a copy to us. Our doc box is being raided lately, and we don’t want anyone else to know about this for … say forty-eight hours.”

“And don’t file it under Allwine’s name or the case number where it can be found,” Carson suggested. “Blind file it under …”

“Munster, Herman,” Michael suggested.

Jack Rogers was smart about a lot more things than viscera. The bags under his eyes seemed to darken as he said, “This isn’t the only weird thing you’ve got, is it?”

“Well, you know the crime scene was strange,” Carson said.

“That’s not all you’ve got, either.”

“His apartment was a freak’s crib,” Michael revealed. “The guy was as psychologically weird as anything you found inside him.”

“What about chloroform?” Carson asked. “Was it used on Allwine?”

“Won’t have blood results until tomorrow,” Jack said. “But I’m not going out on a limb when I say we won’t find chloroform. This guy couldn’t have been overcome by it.”

“Why not?”

“Given his physiology, it wouldn’t have worked as fast on him as on you or me.”

“How fast?”

“Hard to say. Five seconds. Ten.”

“Besides,” Luke offered, “if you tried to clamp a chloroform-soaked cloth over his face, Allwine’s reflexes would have been faster than yours … or mine.”

Jack nodded agreement. “And he would have been strong. Far too strong to have been restrained by an ordinary man for a moment, let alone long enough for the chloroform to work.”

Remembering the peaceful expression on Bobby Allwine’s face when his body lay on the library floor, Carson considered her initial perception that he had welcomed his own murder. She could make no more sense of that hypothesis, however, than she had done earlier.

Moments later, outside in the parking lot, as she and Michael approached the sedan, the light of the moon seemed to ripple through the thick humid air as it might across the surface of a breeze-stirred pond.

Carson remembered Elizabeth Lavenza, handless, floating facedown in the lagoon.

Suddenly she seemed half-drowned in the murky fathoms of this case, and felt an almost panicky need to thrash to the surface and leave the investigation to others.