По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

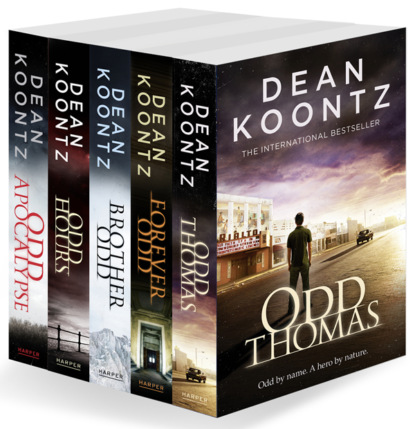

Odd Thomas Series Books 1-5

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It’s August fourteenth. At three-fourteen in the morning on August 14, 1958, his mama died. She was only forty-six.”

“Gladys,” Stormy said. “Her name was Gladys, wasn’t it?”

There is movie-star fame like that enjoyed by Tom Cruise, rock-star fame like that of Mick Jagger, literary fame, political fame ... But mere fame has grown into real legend when people of different generations remember your mother’s name a quarter of a century after your death and nearly half a century after hers.

“Elvis was in the service,” Terri recalled. “August twelfth, he flew home to Memphis on emergency leave and went to his mother’s bedside in the hospital. But the sixteenth of August is a bad day for him, too.”

“Why?”

“That’s when he died,” Terri said.

“Elvis himself?” Stormy asked.

“Yes. August 16, 1977.”

I had finished the second peach brandy.

Terri offered the bottle.

I wanted more but didn’t need it. I covered my empty glass with my hand and said, “Elvis seemed concerned about me.”

“How do you mean?” Terri asked.

“He patted me on the arm. Like he felt sympathy for me. He had this ... this melancholy look, as if he was taking pity on me for some reason.”

This revelation alarmed Stormy. “You didn’t tell me this. Why didn’t you tell me?”

I shrugged. “It doesn’t mean anything. It was just Elvis.”

“So if it doesn’t mean anything,” Terri asked, “why did you mention it?”

“It means something to me,” Stormy declared. “Gladys died on the fourteenth. Elvis died on the sixteenth. The fifteenth, smack between them—that’s when this Robertson sonofabitch is going to go gunning for people. Tomorrow.”

Terri frowned at me. “Robertson?”

“Fungus Man. The guy I borrowed your car to find.”

“Did you find him?”

“Yeah. He lives in Camp’s End.”

“And?”

“The chief and I ... we’re on it.”

“This Robertson is a toxic-waste mutant out of some psycho movie,” Stormy told Terri. “He came after us at St. Bart’s, and when we gave him the slip, he trashed some of the church.”

Terri offered Stormy more peach brandy. “He’s going to go gunning for people, you said?”

Stormy doesn’t drink heavily, but she accepted another round. “Your fry cook’s recurring dream is finally coming true.”

Now Terri looked alarmed. “The dead bowling-alley employees?”

“Plus maybe a lot of people in a movie theater,” Stormy said, and then she tossed back her peach brandy in one swallow.

“Does this also have something to do with Viola’s dream?” Terri asked me.

“It’s too long a story for now,” I told her. “It’s late. I’m whipped.”

“It has everything to do with her dream,” Stormy told Terri.

“I need some sleep,” I pleaded. “I’ll tell you tomorrow, Terri, after it’s all over.”

When I pushed my chair back, intending to get up, Stormy seized my arm and held me at the table. “And now I find out Elvis Presley himself has warned Oddie that he’s going to die tomorrow.”

I objected. “He did no such thing. He just patted me on the arm and then later, before he got out of the car, he squeezed my hand.”

“Squeezed your hand?” Stormy asked in a tone implying that such a gesture could be interpreted only as an expression of the darkest foreboding.

“It’s no big deal. All he did was just clasp my right hand in both of his and squeeze it twice—”

“Twice!”

“—and he gave me that look again.”

“That look of pity?” Stormy demanded.

Terri picked up the bottle and offered to pour for Stormy.

I put my hand over the glass. “We’ve both had enough.”

Grabbing my right hand and holding it in both of hers as Elvis had done, Stormy said insistently, “What he was trying to tell you, Mr. Macho Psychic Batman Wannabe, is that his mother died on August fourteenth, and he died on August sixteenth, and you’re going to die on August fifteenth—the three of you like a hat trick of death—if you don’t watch your ass.”

“That isn’t what he was trying to tell me,” I disagreed.

“What—you think he was just hitting on you?”

“He doesn’t have a romantic life anymore. He’s dead.”

“Anyway,” Terri said, “Elvis wasn’t gay.”

“I didn’t claim he was gay. Stormy made the inference.”

“I’d bet the Grille,” Terri said, “and my left butt cheek that he wasn’t gay.”

I groaned. “This is the craziest conversation I’ve ever had.”

Terri demurred: “Gimme a break—I’ve had a hundred conversations with you a lot crazier than this.”