По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

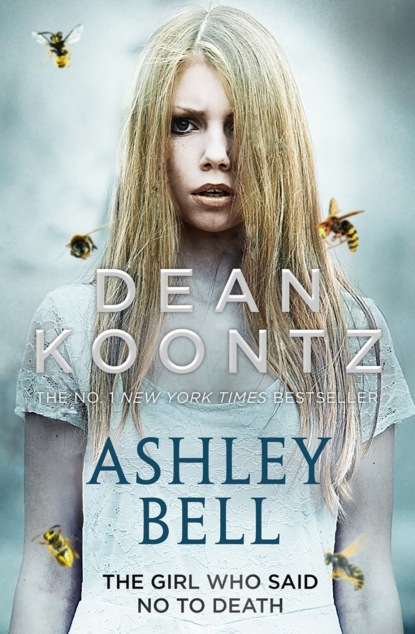

Ashley Bell

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Bibi thought of Charlotte the spider, who saved Wilbur the pig, her friend, in E. B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web. For a moment, Bibi was all but unaware of the garage as an image rose in her mind and became more real to her than reality:

Hundreds of tiny young spiders, Charlotte’s offspring fresh from her egg sac many weeks after her sad death, standing on their heads and pointing their spinnerets at the sky, letting loose small clouds of fine silk. The clouds form into miniature balloons, and the baby spiders become airborne. Wilbur the pig is overcome with wonder and delight, but also with sadness, while he watches the aerial armada sail away to far places, wishing them well but sorry to be deprived of this last connection to his lost friend Charlotte.…

With a thin whine and soft bark, the dog brought Bibi back to the reality of the garage.

Later, after the retriever had been washed and dried and brushed, during a break in the rain, Bibi took him into the house. When she showed him the small bedroom that was hers, she said, “If Mom and Dad don’t blow their tops when they see you, then you’ll sleep here with me.”

The dog watched with interest as Bibi dragged a cardboard box out of the closet. It contained books that wouldn’t fit on the already heavily laden shelves flanking her bed. She rearranged the volumes to create a hollow into which she inserted the chamois-wrapped collar before returning the box to the closet.

“Your name is Olaf,” she informed the retriever, and he reacted to this christening by wagging his tail. “Olaf. Someday, I’ll tell you why.”

In time, Bibi forgot about the collar because she wanted to forget. Nine years would pass before she discovered it at the bottom of that box of books. And when she found it, she folded the chamois around it once more and sought a new place in which to conceal it.

2 (#ulink_d712ca42-40aa-54ab-836d-9b59091200ad)

Twelve Years Later

Another Perfect Day in Paradise (#ulink_d712ca42-40aa-54ab-836d-9b59091200ad)

THAT SECOND TUESDAY IN MARCH, WITH ITS terrible revelations and the sudden threat of death, would have been the beginning of the end for some people, but Bibi Blair, now twenty-two, would eventually call it Day One.

She woke at dawn and stood at the bedroom window, yawning and watching the still-submerged sun announce its approach with banners of coral-pink light, until at last it surfaced and cruised westward. She liked sunrises. Beginnings. Each day started with such promise. Anything good could happen. For Bibi the word disappointment was reserved for evenings, and only if the day had truly, totally sucked. She was an optimist. Her mother had once said that, given lemons, Bibi wouldn’t make lemonade; she would make limoncello.

Silhouetted against the morning blue, the distant mountains seemed to be ramparts protecting the magic kingdom of Orange County from the ugliness and disorder that plagued so much of the world these days. Across the California flatlands, the tree-lined street grids and numerous parks of south county’s planned communities promised a smooth and tidy life of infinite charms.

Bibi needed more than a mere promise. At twenty-two, she had big dreams, though she didn’t call them dreams, because dreams were wish-upon-a-star fantasies that rarely came true. Consequently, she called them expectations. She had great expectations, and she could see the means by which she would surely fulfill them.

Sometimes she was able to imagine her future so clearly that it almost seemed as if she had already lived it and was now remembering. To achieve your goals, imagination was almost as important as hard work. You couldn’t win the prize if you couldn’t imagine what it was and where it might be found.

Staring at the mountains, Bibi thought of the man she would marry, the love of her life now half a world away in a place of blood and treachery. She refused to fear too much for him. He could take care of himself in any circumstances. He was not a fairy-tale hero but a real one, and the woman who would be his wife had an obligation to be as stoic as he was about the risks he faced.

“Love you, Paxton,” she murmured, as she often did, as if that declaration were a charm that would protect him regardless of how many thousands of miles separated them.

After showering and dressing for the day, after snaring the newspaper from the doorstep, she went into the kitchen just as her programmed coffee machine drizzled the sixth cup into the Pyrex pot. The blend she preferred was fragrant and so rich in caffeine that the fumes alone would cure narcolepsy.

The vintage dinette chairs featured chrome-plated steel legs and seats upholstered in black vinyl. Very 1950s. She liked the ’50s. The world hadn’t gone crazy yet. As she sat at a chromed table with a red Formica top, paging through the newspaper, she drank her first coffee of the day, which she called her “wind-me-up cup.”

To compete in an age when electronic media delivered the news long before it appeared in print, the publisher of this paper chose to spend only a few pages on major world and national events in order to reserve space for long human-interest stories involving county residents. As a novelist, Bibi approved. Like good fiction, the best history books were less about big events than about the people whose lives were affected by forces beyond their control. However, for every story about a wife fighting indifferent government bureaucrats to get adequate care for her war-disabled husband, there was another story about someone who acquired an enormous collection of weird hats or who was crusading to be allowed to marry his pet parrot.

Like her first cup, her second coffee was black, and Bibi drank it as she ate a chocolate croissant. In spite of all the propaganda, she didn’t believe that oceans of coffee or a diet rich in butter and eggs was unhealthy. She ate what she wanted, almost in a spirit of defiance, remaining trim and healthy. She had one life, and she meant to live it, bacon and all.

As she ate a second croissant, she got a bite that tasted as rancid as spoiled milk. She spat it onto her plate and wiped her tongue with a napkin.

The bakery she frequented had always been reliable. She could see nothing wrong with the wad of pastry that she had spit out. She sniffed the croissant, but it smelled all right. No visible foreign substance tainted it.

Tentatively, she took another bite. It tasted fine. Or did it? Maybe the faintest trace of … something. She put down the croissant. She had lost her appetite.

That day’s newspaper was thick with weird-hat collectors and the like. She put it aside. Carrying a third cup of coffee, she went to her office in the larger of the apartment’s two bedrooms.

At her computer, when she retrieved the unfinished short story she’d been writing on and off for a few weeks, she stared for a while at her byline: Bibi Blair.

Her parents had named her Bibi, not because they were cruel or indifferent to the travails of a child saddled with an unusual name, but because they were lighthearted to a fault. Bibi, pronounced Beebee, came from the Old French beubelot, meaning toy or bauble. She was no one’s toy. Never had been, never would be.

Another name derived from beubelot was Bubbles. That would have been worse. She would have had to change Bubbles to something less frivolous or otherwise become a pole dancer.

By her sixteenth birthday, she was accustomed to her name. By the time she was twenty, she thought Bibi Blair had a quirky sort of distinction. Nevertheless, sometimes she wondered if she would be taken seriously, as a writer, with such a name.

She scrolled down the page from the byline and stopped at the second paragraph, where she saw a sentence that needed revision. When she began to type, her right hand served her well, but the left fumbled over the keys, scattering random letters across the screen.

Her surprise turned to alarm when she realized that she could not feel the keys beneath her spasming fingers. The sense of touch had deserted them.

Bewildered, she raised the traitorous hand, flexed the fingers, saw them move, but couldn’t feel them moving.

Although coffee had entirely rinsed away the rancid taste that earlier had spoiled her enjoyment of the second croissant, the same foulness filled her mouth again. She grimaced in disgust and, with her right hand, reached for the coffee. The rim of the cup rattled against her teeth, but the brew once more washed her tongue clean.

Her left hand slipped off the keyboard, onto her lap. For a moment, she couldn’t move it, and in panic she thought, Paralysis.

Suddenly a tingling filled the hand, the arm, not that vibratile numbness that followed a sharp blow to the elbow, but a crawling sensation, as if ants were swarming through flesh and bone. As she rolled her chair away from the desk and got to her feet, the tingling spread through the entire left side of her body, from scalp to foot.

Although Bibi didn’t know what was happening to her, she sensed that she was in mortal peril. She said, “But I’m only twenty-two.”

3 (#ulink_642686d8-4370-5e5a-bfc6-6e03e614482b)

The Salon (#ulink_642686d8-4370-5e5a-bfc6-6e03e614482b)

NANCY BLAIR ALWAYS BOOKED THE EARLIEST appointment at Heather Jorgenson’s six-chair salon in Newport Beach because it was her considered opinion that even the best stylists, like Heather, did less dependable work as the day wore on. Nancy would no sooner have her hair cut in the afternoon than she would schedule an after-dinner face-lift.

Not that she needed plastic surgery. At forty-eight, she looked thirty-eight. At worst thirty-nine. Her husband—Murphy, known to all as Murph—said that if she ever let a cosmetic surgeon mess with her face, he would still love her, but he’d start calling her Cruella de Vil, after the stretched-tight villainess in 101 Dalmatians.

She had great hair, too, thick and dark, without a fleck of gray. She got it cut every three weeks because she liked to maintain a precise look.

Her daughter, Bibi, had the same luxurious dark-brown hair, almost black, but Bibi wore hers long. The dear girl was always gently pressing her mother to move on from the short and shaggy style. But Nancy was a doer, a goer, always on the run, and she didn’t have the patience for the endless fussing that was required to look good with a longer do.

After wetting Nancy’s hair with a spray bottle, Heather said, “I read Bibi’s novel, The Blind Man’s Lamp. I really liked it.”

“Oh, honey, my daughter has more talent in one pinkie than most other writers have in their fingers and their thumbs.” Even as she made that declaration with unabashed pride, Nancy realized that it was less than eloquent, even a little silly. Whatever the source of Bibi’s talent for language, it hadn’t come with her mother’s genes.

“It should have been a bestseller,” Heather said.

“She’ll get there. If that’s what she wants. I don’t know if it is. I mean, she shares everything with me, but she’s guarded about her writing, what she wants. A mysterious girl in some ways. Bibi was mysterious even as a child. She was like eight when she made up these stories about a community of intelligent mice that lived in tunnels under our bungalow. Ridiculous stories, but she could almost make you believe them. In fact, we thought for a while she believed in those damn mice. We almost got her therapy. But we realized that she was just Bibi being Bibi, born to tell stories.”

As an ardent consumer of magazines that chronicled the lives of celebrities in plenty of photos and minimal prose, Heather perhaps had not heard Nancy after the third sentence of that long ramble. “But, gee, why wouldn’t she want to be a bestseller—and famous?”

“Maybe she does. But it’s not why she writes. She writes because she has to. She says her imagination is like a boiler that’s all the time building up too much pressure. If she doesn’t let out some of the steam every day, it’ll explode and blow off her head.”

“Wow.” Heather’s face in the mirror, above Nancy’s face, loomed wide-eyed and chipmunky. She was a cute girl. She would have been even cuter if she’d had her upper incisors brought into line with braces.

“Bibi doesn’t mean that literally, of course. Her head isn’t going to explode any more than there were intelligent mice living under our bungalow back in the day.”