По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

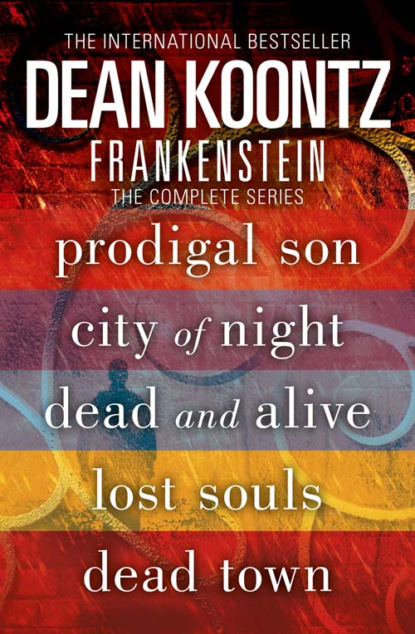

Frankenstein: The Complete 5-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Where they had peeled at the collage, the fourth layer had been revealed below the demons and devils. Freud, Jung. Psychiatrists …

In memory, Carson heard Kathy as they had stood talking with her the previous night in front of this very building: But Harker and I seemed to have such … rapport.

Reading her as he always could, Michael said, “Something?”

“It’s Kathy. She’s next.”

“What’d you find?”

She showed him the appointment card.

He took it from her, turned with it to Deucalion, but Deucalion was gone.

CHAPTER 91 (#ulink_9f15931a-c64b-53e1-a129-313645873f78)

A FRACTION OF THE DAY remains, but filtered through the soot-dark clouds, the light is thin, gray, and weaves itself with shadows to obscure more than illuminate.

For hours, the supermarket shopping cart – piled with garbage bags full of salvaged tin cans, glass bottles, and other trash – has stood where the vagrant left it. No one has remarked upon it.

Randal Six, fresh from the Dumpster, means to push the cart to a less conspicuous place. Perhaps this will delay the discovery of the dead man in the bin.

He curls both hands around the handle of the cart, closes his eyes, imagines ten crossword squares on the pavement in front of him, and begins to spell shopaholic. He never finishes the word, for an amazing thing happens.

As the shopping cart rolls forward, the wheels rattle across the uneven pavement; nevertheless, the motion is remarkably, satisfyingly smooth. So smooth and continuous is this motion that Randal finds he can’t easily think of his progress as taking place letter by letter, one square at a time.

Although this development spooks him, the relentless movement of the wheels through squares, rather than from one square to another in orderly fashion, doesn’t bring him to a halt. He has … momentum.

When he arrives at the second o in shopaholic, he stops spelling because he is not any longer sure which of the ten imagined squares he is in. Astonishingly, though he stops spelling, he keeps moving.

He opens his eyes, assuming that when he no longer visualizes the crossword boxes in his mind’s eye, he will come to a sudden stop. He keeps moving.

At first he feels as if the cart is the motive force, pulling him along the alleyway. Although it lacks a motor, it must be driven by some kind of magic.

This is frightening because it implies a lack of control. He is at the mercy of the shopping cart. He must go where it takes him.

At the end of a block, the cart could turn left or right. But it continues forward, across a side street, into the next length of the alleyway Randal remains on the route that he mapped to the O’Connor house. He keeps moving.

As the wheels revolve, revolve, he realizes that the cart is not pulling him, after all. He is pushing the cart.

He experiments. When he attempts to increase speed, the cart proceeds faster. When he chooses a less hurried pace, the cart slows.

Although happiness is not within his grasp, he experiences an unprecedented gratification, perhaps even satisfaction. As he rolls, rolls, rolls along, he has a taste, the barest taste, of what freedom might be like.

Full night has fallen, but even in darkness, even in alleyways, the world beyond Mercy is filled with more sights, more sounds, more smells than he can process without spinning into panic. Therefore, he looks neither to the left nor the right, focuses on the cart before him, on the sound of its wheels.

He keeps moving.

The shopping cart is like a crossword-puzzle box on wheels, and in it is not merely a collection of aluminum cans and glass bottles but also his hope for happiness, his hatred for Arnie O’Connor.

He keeps moving.

CHAPTER 92 (#ulink_68249995-562d-5936-8cb2-c0178cb3e283)

IN THE BUNGALOW of the seashell gate with the unicorn motif, behind the windows flanked by midnight-blue shutters decorated with star shapes and crescent moons, Kathy Burke sat at her kitchen table reading a novel about adventure in a kingdom ruled by wizardry and witchery, eating almond cookies and drinking coffee.

From the corner of her eye, she saw movement and looked up to discover Jonathan Harker standing in the doorway between the kitchen and the dark hall.

His face, usually red from the sun or from anger, was whiter than pale. Disheveled, sweating, he looked malarial.

Although his eyes were wild and haunted, although his nervous hands plucked continually at his stretched and saturated T-shirt, he spoke in a meek and ingratiating manner weirdly out of sync with his aggressive entrance and his appearance: “Good evening, Kathleen. How’re you? Busy, I’m sure. Always busy.”

Taking her lead from his tone, Kathy calmly put a bookmark in her novel, slid it aside. “It didn’t have to be this way, Jonathan.”

“Maybe it did. Maybe there was never any hope for me.”

“It’s partly my fault that you are where you are. If you’d stayed in counseling—”

He took a step into the room. “No. I’ve hidden so much from you. I didn’t want you to know … what I am.”

“I’ve been a lousy therapist,” she said by way of ingratiation.

“You’re a good woman, Kathy. A very fine person.”

The weirdness of this exchange – her self-effacement, Harker’s flattery – in light of his recent crimes, was impossible to sustain, and Kathy thought furiously about where the encounter might lead and how best to manage it.

Fate intruded when the phone rang.

They both looked at it.

“I’d prefer you didn’t answer that,” said Harker.

She remained seated and did not challenge him. “If I’d insisted that you keep your appointments, I might have recognized signs that you were … heading for trouble.”

A third ring of the phone.

He nodded. His smile was tortured. “You would have. You’re so insightful, so understanding. That’s why I was afraid to talk with you anymore.”

“Will you sit down, Jonathan?” she asked, indicating the chair across the table from her.

A fifth ring.

“I’m so tired,” he acknowledged, but he made no move toward the chair. “Do I disgust you … what I’ve done?”

Choosing her words carefully, she said, “No. I feel … a kind of grief, I guess.”

After the seventh or eighth ring, the phone fell silent.

“Grief,” she continued, “because I so much liked the man you were … the Jonathan I knew.”