По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

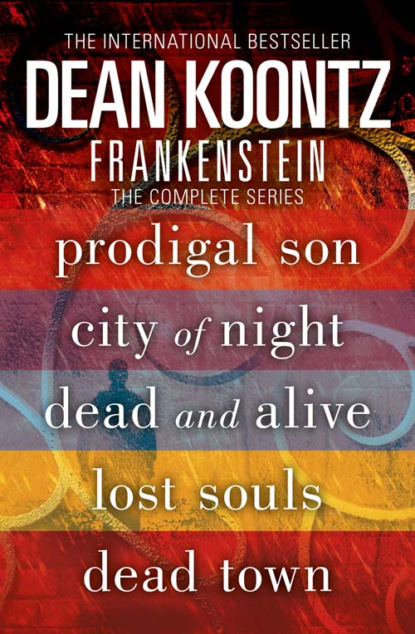

Frankenstein: The Complete 5-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Roy was captivated. Her eyes were priceless gems displayed in a cluttered and dusty case, a striking greenish blue.

The skin around her eyes crinkled alluringly as she caught his attention and smiled. “Can I help you?”

Roy stepped forward. “I’d like something sweet.”

“All I’ve got is cotton candy.”

“Not all,” he said, marveling at how suave he could be.

She looked puzzled.

Poor thing. He was too smooth for her.

He said, “Yes, cotton candy, please.”

She picked up a paper cone and began to twirl it through the spun sugar, wrapping it with a cloud of sugary confection.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

She hesitated, seemed embarrassed, averted her eyes. “Candace.”

“A girl named Candy is a candy vendor? Is that destiny or just a good sense of humor?”

She blushed. “I prefer Candace. Too many negative connotations for a … a heavy woman to be called Candy.”

“So you’re not an anorexic model, so what? Beauty comes in lots of different packages.”

Candace obviously had seldom if ever heard such kind words from an attractive and desirable man like Roy Pribeaux.

If she herself ever thought about a day when she would excrete no wastes, she must know that he was far closer to that goal than she was.

“You have beautiful eyes,” he told her. “Strikingly beautiful eyes. The kind a person could look into for years and years.”

Her blush intensified, but her shyness was overwhelmed by astonishment to such a degree that she made eye contact with him.

Roy knew he dared not come on to her too strong. After a life of rejection, she’d suspect that he was setting her up for humiliation.

“As a Christian man,” he explained, though he had no religious convictions, “I believe God made everyone beautiful in at least one respect, and we need to recognize that beauty. Your eyes are just … perfect. They’re the windows to your soul.”

Putting the cloud of cotton candy on a counter-top holder, she averted her eyes again as though it might be a sin to let him enjoy them too much. “I haven’t gone to church since my mother died six years ago.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. She must have died so young.”

“Cancer,” Candace revealed. “I got so angry about it. But now … I miss church.”

“We could go together sometime, and have coffee after.”

She dared his stare again. “Why?”

“Why not?”

“It’s just … You’re so …”

Pretending a shyness of his own, he looked away from her. “So not your type? I know to some people I might appear to be shallow—”

“No, please, that’s not what I meant.” But she couldn’t bring herself to explain what she had meant.

Roy withdrew a small notepad from his pocket, scribbled with a pen, and tore off a sheet of paper. “Here’s my name – Ray Darnell – and my cell-phone number. Maybe you’ll change your mind.”

Staring at the number and the phony name, Candace said, “I’ve always been pretty much a … private person.”

The dear, shy creature.

“I understand,” he said. “I’ve dated very little. I’m too old-fashioned for women these days. They’re so … bold. I’m embarrassed for them.”

When he tried to pay for his cotton candy, she didn’t want to take his money. He insisted.

He walked away, nibbling at the confection, feeling her gaze on him. Once out of sight, he threw the cotton candy in a trash can.

Sitting on a bench in the sun, he consulted the notepad. On the last page at the back of it, he kept his checklist. After so much effort here in New Orleans and, previously, elsewhere, he had just yesterday checked off the next-to-last item: hands.

Now he put a question mark next to the final item on the list, hoping that he could cross it off soon.

EYES?

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_7f6fdd69-8181-503e-9c50-97710d5bf08d)

HE IS A CHILD of Mercy, Mercy-born and Mercy-raised.

In his windowless room he sits at a table, working with a thick book of crossword puzzles. He never hesitates to consider an answer. Answers come to him instantly, and he rapidly inks letters in the squares, never making an error.

His name is Randal Six because five males have been named Randal and have gone into the world before him. If ever he, too, went into the world, he would be given a last name.

In the tank, before consciousness, he’d been educated by direct-to-brain data downloading. Once brought to life, he had continued to learn during sessions of drug-induced sleep.

He knows nature and civilization in their intricacies, knows the look and smell and sound of places he has never been. Yet his world is largely limited to a single room.

The agents of Mercy call this space his billet, which is a term to describe lodging for a soldier.

In the war against humanity – a secret war now but not destined to remain secret forever – he is an eighteen-year-old who came to life four months ago.

To all outward appearances, he is eighteen, but his knowledge is greater than that of most elderly scholars.

Physically, he is sound. Intellectually, he is advanced.

Emotionally, something is wrong with him.

He does not think of his room as his billet. He thinks of it as his cell.