По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

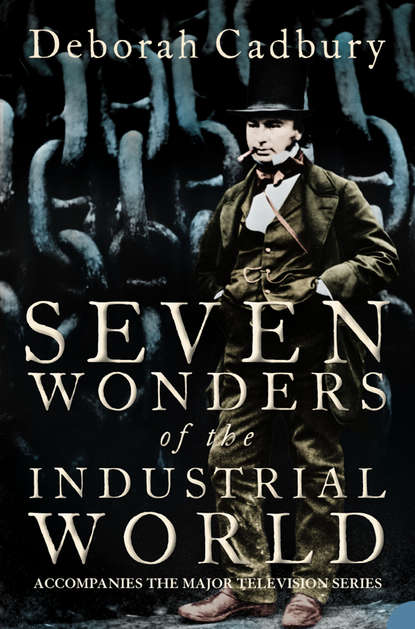

Seven Wonders of the Industrial World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

However, the optimism of the summer dissolved as endless difficulties connected with the launch arose. After much negotiation, a new launch date was agreed with Martin’s Bank for October 1857. If the ship was not in the Thames by this date, the creditors would claim the yard and ‘we will be in the hands of the Philistines,’ declared company secretary John Yates. The fifth of October arrived and Brunel, not satisfied that everything was ready for the launch, had no alternative but to defer the date once again. The mortgagees seized the yard and refused access to all working on the ship. The situation had become impossible. Brunel was now put under immense pressure to agree to launch on the next ‘spring tide’ of 3 November and the company was charged large fees for the delay.

As the Great Ship stood helplessly inert, waiting at the top of two launch-ways, her brooding shape invited much comment. Many thought she was unlaunchable and would rust where she was. Other wise ‘old salts’ predicted that if she ever did finally find the sea, the first wave would break her long back in half. Brunel never doubted; but no matter how carefully he planned the coming operation, there were still many unknowns and little time to test the equipment. In the small hours of the cold autumn nights it seemed he was attempting the impossible. He was proposing to move an unwieldy metal mountain more than four storeys high down a precarious slope towards a high tide with untried equipment.

The plan for launching the ship sounded simple. Hydraulic rams would gently persuade her down the launch-ways. Tugs in the river, under the command of Captain Harrison, could also ease her towards the river, and there were restraining chains to hold her back should she move too fast. Two wooden cradles, 120 feet wide, were supporting the ship and they rested on launch-ways of the same width. Iron rails were fixed to the launch-ways and iron bars 1 inch thick were attached to the base of the cradles and both surfaces were greased to enable the vessel to slide easily down the launch-way gradient.

As the spring tide of 3 November approached, work on the ship became more frenzied. At night, 1,500 men working by gaslight carried on with last minute instructions from Brunel. Brunel himself never left the yard, sleeping for a few hours when exhausted on a makeshift bed in a small wooden office. He issued special instructions to everyone involved with the launch, saying:

The success of the operation will depend entirely upon the perfect regularity and absence of all haste or confusion in each stage of the proceedings and in every department, and to attain this nothing is more essential than perfect silence. I would earnestly request, therefore, that the most positive orders be given to the men not to speak a word, and that every endeavour should be made to prevent a sound being heard, except the simple orders quietly and deliberately given by those few who will direct.

Unfortunately for Brunel, perfect silence was not a high priority with the board of the Eastern Steam Navigation Company. For months now, the company had borne the disastrous haemorrhage of enormous amounts of money into the Great Ship. The launching presented them with a small chance to recoup some of those losses. Unknown to Brunel, they had sold over 3,000 tickets to view the launch from Napier shipyard. Newspapers, too, had played their part, informing the public that an event worthy of comparison with the Colosseum was about to take place at Millwall. ‘Men and women of all classes were joined together in one amicable pilgrimage to the East,’ reported The Times. ‘For on that day at some hour unknown, the Leviathan was to be launched at Millwall … For two years, London – and we may add the people of England – had been kept in expectation of the advent of this gigantic experiment, and their excitement and determination to be present at any cost are not to be wondered at when we consider what a splendid chance presented itself of a fearful catastrophe.’

The launch place of the Leviathan presented a chaotic picture to Charles Dickens. ‘I am in an empire of mud … I am surrounded by muddy navigators, muddy engineers, muddy policemen, muddy clerks of works, muddy, reckless ladies, muddy directors, muddy secretaries and I become muddy myself.’ He noted that ‘a general spirit of reckless daring’ seemed to animate the ‘one hundred thousand souls’ crammed in and around the yard, upon the river and the opposite bank. ‘They delight in insecure platforms, they crowd on small, frail housetops, they come up in little cockleboats, almost under the bows of the Great Ship … many in that dense floating mass on the river and the opposite shore would not be sorry to experience the excitement of a great disaster.’

In the dull light of the November morning the scene that greeted Brunel as he emerged from his makeshift quarters was one of confusion and noise, with uncontrollable crowds swarming over his carefully placed launch equipment. All of fashionable London, displaying intense curiosity, expecting to be amused, charmed, and hopefully thrilled, was taking the air in Napier shipyard. Then, almost farcically, in the midst of preparations, a string of unexpected distinguished visitors turned up in all their finery, first the Comte de Paris and then, complete with a retinue resplendent in gold cloth, the ambassador of Siam. A half-hearted attempt at a launching ceremony saw the daughter of Mr Hope, the chairman of the board, offering the token bottle of champagne to the ship. Brunel refused to associate himself with it. She got the name wrong, christening the ship ‘Leviathan’, which nobody liked since all of London had already decided on the Great Eastern.

The whole colourful funfair scene was terribly at odds with the cold, clinically precise needs of the launching operation. Brunel felt betrayed, as he later told a friend: ‘I learnt to my horror that all the world was invited to “The Launch”, and that I was committed to it coûte que coûte. It was not right, it was cruel; and nothing but a sense of the necessity of calming all feelings that could disturb my mind enabled me to bear it.’

Brunel had no alternative but to make the attempt in spite of the difficulties. He stood high up on a wooden structure, against the hull, his slight figure wearing a worn air, stovepipe hat at an angle, habitual cigar in his mouth. He held a white flag in his hand, poised like a conductor waiting to begin the vast unknown music.

As his flag came down, the wedges were removed, the checking drum cables eased, and the winches on the barges mid-river took the strain. For what seemed an eternity, nothing happened. The crowd, which had been quiet, grew restive. Brunel decided to apply the power of the hydraulic presses. Suddenly, with thunderous reverberation, the bow cradle moved three feet before the team applied the brake lever on the forward checking drum. Immediately, accompanied by a rumbling noise, the stern of the great hull moved four feet. An excited cry went up from the crowd: ‘She moves! She moves!’ In an instant the massive cables of the aft checking drum were pulled tight, causing the winch handle to spin. As the winch handle ‘flew round like lightning’, it sliced into flesh and bone, and tossed the men who were working the drum into the air like flotsam. The price the team paid for not being entirely awake to the quickly changing situation was four men mutilated. Another man, the elderly John Donovan, sustained such fearful injuries he was considered a hopeless case and was taken to a nearby hospital where he soon died.

Later that afternoon, Brunel tried to move the hull once more but a string of minor accidents and the growing dark persuaded him to finish for the day. In the words of Brunel’s 17-year-old son Henry, ‘the whole yard was thrown into confusion by a struggling mob, and there was nothing to be done but to see that the ship was properly secured and wait till the following morning’.

The spring tide had come and gone, the next one was not for another month; another month of extortionate fees while the ship lay on the slipway. Brunel was determined to get the ship completely on to the launch-ways as soon as possible. He was very concerned that while the ship was half on the building slip (whose foundation was completely firm) and half on the launch-ways (which had more give) the bottom of the hull could be forced into a different shape. His urgent task was to get the ship well down the launch-ways to the water’s edge in case the hull started to sink into the Thames mud under its immense weight. The fiasco of 3 November at least provided information on how to manage the launch more effectively. Some alterations were made to improve the equipment and another attempt at the launch was made on the nineteenth. This was a huge disappointment with the hull moving just 1 inch. Clearly, more would have to be done.

The winches on the barges mid-river had been ineffective and all four were now mounted in the yard, their cables drawn under the hull and across to the barges; but even chains of great strength and size broke when any strain was put on them. ‘Dense fog made it almost impossible to work on the river,’ observed Henry Brunel. ‘Moreover, there seemed a fatality about every attempt to get a regular trial of any part of the tackle.’ Two more hydraulic presses were added to the original two, giving a force of 800 tons at full power.

By 28 November, Brunel felt confident enough to try to move the Great Ship once more. From a central position in the yard, Brunel signalled his instructions with a white flag. The hydraulic presses were brought up to full power and, to the accompaniment of terrifying sounds of cracking timber and the groaning and screeching of metal, slowly the ship moved at a rate of one inch per minute. As before, though, the tackle between the hull and the barges proved unreliable and Captain Harrison and his team found themselves endlessly repairing chains. In spite of the difficulties, by the end of the day the ship had been moved fourteen feet and there was renewed hope of floating the ship on the high tide of 2 December. An early start on 29 November saw the river tackle yet again let them down and the four hydraulic presses pushed to their maximum could not move the ship. Hydraulic jacks and screw jacks were begged and borrowed and by nightfall another 8 feet had been claimed so that by the thirtieth the ship had moved 33 feet in total and hope now had real meaning. But then one of the presses burst a cylinder, which killed off any possibility of a December launch.

Brunel would not be defeated though, and throughout December he carried on inching the colossal black ship down the launch-ways. Each day it was becoming more reluctant to start. ‘While the ship was in motion,’ noted Henry Brunel, ‘the whole of the ground forming the yard would perceptibly shake, or rather sway, on the discharge of power, stored up in the presses and their abutments.’ In the freezing fogs of December and January, the hundreds of workers were heard, rather than seen, as the yard echoed with the sounds of orders and endless hammering. The gangs sang to relieve their boredom as they mended the chains. At night, gas flares lit the scene and fires burned by the pumps and presses to stop them freezing up. With the small figures of the workers beneath the huge black shape in the mist, which was red from the many fires, it gave the impression that some unearthly ritual was being enacted on this bleak southerly bend in the Thames.

Brunel was coming to the conclusion that the pulling power he had hoped to obtain from the barges and tugs on the river was not going to be enough and that his best hope lay in providing much more power to push the ship into the river. The railway engineer, Robert Stephenson, a friend who had come to view the operation, agreed and orders were placed with a Birmingham firm, Tangye Bros, for hydraulic presses capable of much more power.

The whole country was following Brunel’s efforts to launch the reluctant ship and the press were increasingly critical. ‘Why do great companies believe in Mr Brunel?’ scoffed The Field. ‘If great engineering consists in effecting huge monuments of folly at enormous cost to share holders, then is Mr Brunel surely the greatest of engineers!’ There was no shortage of letters offering diverse advice. One reverend gentleman thought the best plan was to dig a trench up to the bows and then push the ship in. Another claimed that 500 troops marching at the double round the deck would set up vibrations that would move the vessel. Yet another idea was to float the ship to the river on cannon balls or even shoot cannon balls into the cradles. Scott Russell, too, aired his theories on just why the ship was ‘seizing up’ and reluctant to move. He suggested the two moving surfaces should have been wood not iron.

December and January were bitterly cold. By day, the ship looked mysterious in dense fogs; the nights were black as the river itself. Brunel stood alone against a background of criticism; his sheer unremitting determination to get the ship launched permeated every impulse. By early January, he had acquired eighteen hydraulic presses and they were placed nine at each of the cradles. It was thought that their combined power was more than 4,500 tons.

The new hydraulic presses were so successful that as the month advanced the Thames water was lapping her hull. The next high tide of the thirtieth was set for launch day. But the night of the twenty-ninth brought sheeting horizontal rain and a strong southwesterly wind. Brunel knew that if they got the ship launched, the difficulties of managing the craft in the shallow waters of the Thames, where at this point it was not much wider than the length of the ship, would be considerable in such high winds. Miraculously, though, 31 January was still and calm. The Thames shimmered like a polished surface.

At first light, Brunel started the launch process in earnest. Water which had been pumped into the ship the day before to hold her against the strong tide was now pumped out. The bolts were removed from wedges that were holding the ship. Nothing more could be done until the tide came up the river, which it did with surprising speed and force. Messengers were sent with desperate urgency to collect the men in order not to miss the opportunity which seemed to have arrived at last. The hydraulic presses were noisy with effort and the great Tangye’s rams hissed and pushed at the massive structure. Two hours of shoving and straining and tension down the last water-covered part of the launch-ways saw the vast iron stern afloat. The forward steam winch hauled and, quickly, the huge bow responded and moved with solemn deliberation into the water. There were no crowds to witness this defining moment; just a few curious onlookers there by accident as the colossal ship moved from one element to another. As the news spread, bells rang out across London as the Great Eastern floated for the first time.

Brunel, who had not slept for 60 hours, was able to board with his wife and son and at last could feel the movement of the ship as she responded to the currents of the Thames beneath her. Four tugs took the Great Eastern across the river to her Deptford mooring where she could now be fitted out. The cost of the launch was frightening – some estimates suggest as much as £1,000 per foot – and the ship had so far consumed £732,000, with Brunel putting in a great deal of his own money. But the cost to Brunel’s health was higher still. Over the past few months he had pushed himself to the limits of endurance. It seemed the Great Ship owned him in body and soul and gave him no relief from the endless difficulties of turning his original vision into a reality. Now that the Great Eastern was finally in the water after years, Brunel’s doctors insisted that he take a rest.

When Brunel returned in September 1858 he found that the Eastern Steam Navigation Company was in debt, that there was no money to fit the ship out and there was talk of selling her. The company tried to raise £172,000 to finish the work on the ship, but this proved impossible. The financial problems of the board were only resolved when they formed a new company, ‘the Great Ship Company’, which bought the Great Eastern for a mere £160,000, and allotted shares to shareholders of Eastern Steam in proportion to their original holding. Brunel was re-engaged as engineer and, with his usual energy, became busy with designs for every last detail, even the skylights and rigging. Yet he was harassed now with health problems and doctors diagnosed his recurring symptoms as ‘Bright’s disease’, with progressive damage to his kidneys. They insisted that he must spend the winter relaxing in a warmer climate. The last thing Brunel wanted was to leave his Great Ship when there was still so much to supervise. Reluctantly, he agreed to travel to Egypt with his wife and son, Henry.

Before he left, with memories of the impossible position that the board had faced when dealing with Scott Russell, he urged them to ensure that any contract they entered into for fitting out the ship was absolutely binding. However, with Brunel abroad and clearly unwell, the board, left with bringing to completion such a unique vessel, opted for the devil they knew. Scott Russell had built the hull and he was building the paddle engines. He was, after Brunel, the man who knew most about the Great Ship. It was not long before the charming, charismatic Scott Russell with his delightfully low-priced, somewhat ambiguous contract was back on board.

In May 1859, Brunel returned. The enforced holiday appeared to have been beneficial and his friends were hopeful that he was fully recovered. Privately, he knew this was not the case. His doctors had made it quite clear that his disease was progressing relentlessly. Only so much time was left for him and he should certainly not overexert himself. Yet, for Brunel, rest was out of the question. Whatever private bargain he may have made with himself, it proved impossible for him to resist the pull of the Great Eastern. His ship came first, whatever the cost.

With the maiden voyage planned for September, all Brunel could see was the enormous amount still needing to be done. So he rented a house near the ship and, with his usual energy, dealt daily with the many problems that needed his expert attention. Everything from the engine room to the rigging was checked; the best price of coal ascertained; the crew for the sea trials named; progress reports on the screw engines prepared; notes for Captain Harrison; advice on the decoration in the grand saloon: nothing escaped his practised eye. On 8 August 1859, a grand dinner was given for MPs and members of the House of Lords in the richly gilded rococo saloon but Brunel was too exhausted to attend. It was a glamorous occasion and, in Brunel’s absence, Scott Russell rose to it, shining in the glowing approbation of the distinguished audience.

On 5 September, Brunel was back on board his ship. He had chosen his cabin for the maiden voyage and stood for a moment on deck by the gigantic main mast while the photographer recorded the event. He had lost weight; his face was thinner, his clothes hung on him. In one hand he held a stick to help him get about; his shoes were clean and polished. He had a fragile, expended air. As he looked at the camera – his eyes, as always, concentrating, absorbed in some distant prospect – he looked like a man with little time left. Just two hours later he collapsed with a stroke. He was still conscious as his colleagues carried him very carefully to his private coach and slowly drove him home to Duke Street as though he were breakable.

The Great Eastern made her way alone now, without Brunel’s attention, directed by fussing tugs down the Thames to Purfleet in Essex and beyond for her sea trials. Once out to sea, she was magnificent. ‘She met the waves rolling high from the Bay of Biscay,’ reported The Times. ‘The foaming surge seemed but sportive elements of joy over which the new mistress of the ocean held her undisputed sway.’

With Brunel lying paralysed at home in Duke Street, Captain Harrison was now in charge, but his command was diluted as the engine trials took place. The two engine rooms were supervised by the representatives of the firms responsible for the engines; Scott Russell put his man Dixon in charge of the paddle engine room. Brunel had designed many new and innovative features for the smoother running of his ship, some of which those in charge were neither familiar with nor even aware existed. No one had the same intimate understanding of the complex workings of the ship as Brunel and if his familiar figure had been on board, in total charge with his boundless energy and sharp mind directing proceedings, it is possible the accident would never have happened.

The Great Eastern was steaming along, just off Hastings, cutting smoothly through the waves and making light work of the choppy seas that were tossing the smaller boats dangerously around her. Passengers on board had left the glittering chandeliered saloon to dine; a hardier group had gathered in the bow to view the distant land. Suddenly, without warning, there was a deafening roar that seemed to come from deep within the bowels of the ship, and the forward funnel was wrenched up and shot 50 feet in the air, accompanied by a huge cloud of steam under pressure. Up in the air was tossed the forward part of the deck and all the glitter and glory of the saloon in the catastrophic eruption. Passengers were stunned, almost blinded by the white cloud of steam, and then the debris came crashing down.

Captain Harrison seized a rope and lowered himself down through the steam into the wreck of the grand saloon. He found his own little daughter, who by a miracle had escaped unhurt. The accident, it was clear, was in the paddle engine room, which had suddenly been filled with pressurised steam. Several dazed stokers emerged on deck with faltering steps, their faces fixed in intense astonishment, their skins a livid white. ‘No one who had ever seen blown up men before could fail to know that some had only two or three hours to live,’ reported The Times. ‘A man blown up by gunpowder is a mere figure of raw flesh, which seldom moves after the explosion. Not so men who are blown up by steam, who for a few minutes are able to walk about, apparently almost unhurt, though in fact, mortally injured beyond all hope of recovery.’ Since they could walk, at first it was hoped that their injuries were not life threatening. But they had met the full force of the pressurised steam; they had effectively been boiled alive. One man was quite oblivious to the fact that deep holes had been burnt into the flesh of his thighs. A member of the crew went to assist another of the injured and, catching him by the arm, watched the skin peel off like an old glove. Yet another stoker running away from the hell below leapt into the sea, only to meet his death in the blades of the paddle wheel.

‘A number of beds were pulled to pieces for the sake of the soft white wool they contained,’ reported Household Words,

and when the half-boiled bodies of the poor creatures were anointed with oil, they were covered over with this wool and made to lie down. They were nearly all stokers and firemen, whose faces were black with their work, and one man who was brought in had patches of red raw flesh on his dark, agonised face, like dabs of red paint, and the skin of his arms was hanging from his hands like a pair of tattered mittens … As they lay there with their begrimed faces above the coverlets, and their chests covered with the strange woolly coat that had been put upon their wounds, they looked like wild beings of another country whose proper fate it was to labour and suffer differently from us.

Among the crew, the fate of the riveter and his boy, locked alive in the hull years before, resurfaced, with prophesies of worse to come.

The Great Ship sailed confidently on, her engines pounding, not even momentarily stopped in her tracks, just as her designer envisaged. Such an accident would have foundered any other ship. The stunned passengers were at a loss to know what had happened, and were totally unaware that the whole explosive performance could be repeated at any minute with a second funnel. The accident had been caused by a forgotten detail: a stopcock had been inadvertently turned off, allowing a water jacket in the forward funnel to explode under pressure. There was a similar stopcock also affecting a second funnel – also switched off, also building up enormous pressure. By a miracle, one of Scott Russell’s men from the paddle engine room realised what had happened and sent a greaser to open the second stopcock. A great column of steam was released and the danger passed.

Twelve men had been injured; five men were dead. An inquest was held in Weymouth in Dorset. It proved difficult to ascertain just who had responsibility for the stopcock. Scott Russell, smoothly evasive, claimed that he had been on board merely in an advisory capacity and that the paddle engines and all connected with them were the total responsibility of the Great Ship Company. ‘I had nothing whatever directly or indirectly to do,’ he said. ‘I went out of personal interest and invited Dixon as my friend.’ He claimed he had ‘volunteered his assistance only when it became obvious to him that the officers in charge were having difficulty in handling the ship’. All the other witnesses also disclaimed responsibility. There were, however, passengers on the ship who insisted that they had heard Scott Russell ‘give at least a hundred orders from the bridge to the engine room’. The truth, though, was undiscoverable, lost somewhere in the maze of evidence from the variously interested parties. Accidental death was the verdict from the jury.

At his home in Duke Street, Brunel, a shadow but still clinging to life, was waiting patiently through the dull days for word of the sea trials. Paralysed, he lay silently, hoping for good news, hoping so much to hear of her resounding success. Instead, he was told of the huge explosion at sea and the terrible damage to the ship. It was a shock from which he could not recover. It was not the right news for a man with such a fragile hold on life. He died on 15 September, just six days after the explosion on his beloved Great Eastern, still a relatively young man at the age of 53.

The country mourned his loss; the papers eulogised. A familiar brilliant star was suddenly out. ‘In the midst of difficulties of no ordinary kind,’ said the president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Joseph Locke, ‘and with an ardour rarely equalled, and an application both of body and mind almost beyond the limit of physical endurance in the full pursuit of a great and cherished idea, Brunel was suddenly struck down, before he had accomplished the task which his daring genius had set before him.’

With her creator gone, the Great Ship put in to Weymouth on the south coast for repairs that would bring her up to Board of Trade requirements. While work was in progress, sightseers at 2s 6d per head came in their thousands to wonder and whisper if the ship was damned. Was there not a story about a riveter and his boy and bad luck? Since the repairs took longer than expected the company postponed plans for the maiden voyage until the following spring and, as the sightseers had proved financially successful, the Great Ship steamed on to Holyhead in Anglesey, Wales, to find some more.

While there she encountered a fearsome storm with gale force winds and rivers of rain. The crashing waves broke the skylights, deluged the ship and ruined the décor in the grand saloon. Captain Harrison realised she had lost her mooring chains and was at the mercy of the storm. He ordered the engineer to start the paddle engines and, by skilfully keeping her head into the wind, the Great Eastern rode out the storm that saw many wrecked around her. Nearby, the steamship Royal Charter went down with 446 lives, further evidence that the Great Eastern was unsinkable as her creator had claimed. It was decided that Southampton would be a more sheltered port for the winter.

It was, however, a troubled winter for the Great Eastern and those connected with her. At a special shareholders’ meeting, the news that there was a mortgage of £40,000 attached to the ship and the company was over £36,000 in debt led to angry calls for the directors to resign. A new board of directors led by Brunel’s friend, Daniel Gooch, was voted in. They issued shares in the hope of raising £100,000 to complete the ship but doubts were raised over the terms of the contract with Scott Russell and, above all, how £353,957 had been expended on a ship still not fit for sea. Once again, Scott Russell’s loosely defined estimate for fitting out the ship had been wildly exceeded. The services of Scott Russell were finally dispensed with and Daniel Gooch was elected chief engineer.

Yet more bad luck seemed to haunt those connected with the ship. One January day in the winter of 1860, Captain Harrison with some members of the crew set out from Hythe pier on Southampton Water to reach the Great Eastern in a small boat. As they left the shelter of the land, they were hit by a sudden violent squall. The tide was very high with choppy, dangerous seas. Harrison ordered the sail down, but the wet sail would not budge. The rest occurred in just a minute. The wind hit the sail and turned the boat over. Captain Harrison, always cool and collected, made repeated attempts to right the boat, but it kept coming up keel first. Buffeted by wild and stifling seas, he seemed almost powerless. Very quickly, the sea claimed the ship’s boy, the coxswain, and master mariner Captain Harrison himself. The Great Eastern had lost her captain hand-picked by Brunel.

Almost two years had elapsed since the launch and the ship had still not made a trip to Australia as originally planned. With the continued shortage of funds this was difficult to finance and, instead, the Great Ship Company decided to sail her as a luxury liner on the Atlantic. In June 1860, the Great Eastern finally sailed for New York on her maiden voyage. On board were just 38 passengers, who marvelled at the great ship, fascinated by the massive engines, the imposing public rooms, the acres of sail. Despite the small number of people on board, they were in champagne mood, enjoying dancing, musicals and a band and strolling the wide deck as they walked to America with hardly a roll from the Great Eastern. The crew, 418 strong, took her across the Atlantic as though she were crossing a millpond.

‘It is a beautiful sight to look down from the prow of this great ship at midnight’s dreary hour, and watch the wondrous facility with which she cleaves her irresistible way through the waste of waters,’ reported The Times. ‘A fountain, playing about 10 feet high before her stem, is all the broken water to be seen around her; for owing to the great beauty of her lines, she cuts the waves with the ease and quietness of a knife; her motion being just sufficient to let you know that you have no dead weight beneath your feet, but a ship that skims the waters like a thing of life …’

When she reached New York, on 27 June, people turned out in their thousands to view her; they packed the wharfs, the docks, the houses. ‘They were in every spot where a human being could stand,’ observed Daniel Gooch. A 21-gun salute was fired and the ecstatic crowds roared their approval. All night in the moonlight, people tried to board her and the next day an impromptu fairground had gathered selling Great Eastern lemonade and oysters and sweets. Over the next month, the streets were choked with sightseers and the hotels were full as people were drawn from all over America to view this great wonder. The Great Eastern was the toast of New York. Her future as a passenger ship seemed assured.

In the mid-nineteenth century, sea travel was hazardous. Many ships were lost but the Great Eastern was proving to be unsinkable. Confidence in her was rising. She had survived the terrible ‘Royal Charter storm’ and, with her double hull and transverse and longitudinal watertight bulkheads, she would laugh at rough weather. It was thought her hull was longer than the trough of the greatest storm wave.

And so it was with a mood of great optimism that the Great Eastern left Liverpool under full sail on 10 September 1861, in such soft summer weather that some of her 400 passengers were singing and dancing on deck. The next morning was grey with a stiff breeze blowing spray. By lunchtime they were meeting strong winds and heavy seas and by the afternoon, when they were 300 miles out in the Atlantic, the winds were gale force. ‘She begins to roll very heavily and ship many seas,’ wrote one anxious passenger. ‘None but experienced persons can walk about. The waves are as high as Primrose Hill.’

With waves breaking right over the ship, the Great Eastern soon leaned to such an extent that the port paddle wheel was submerged. The captain, James Walker, became aware of a sound of machinery crashing and scraping from the paddle wheel. Clinging on to the rails, he lowered himself towards the ominous sounds. As the Great Ship lurched through the waves and the paddle wheel was flung under water, Walker was pulled into the sea right up to his neck. When he got a chance to investigate he could see planks splitting, girders bending and the wheel scraping the side of the ship so badly that it looked as though it might hole her. Somehow, he clambered back to the bridge and gave the order to stop the paddle engines. But without these, the screw engines alone could not provide enough power to control the ship’s movement in what was fast turning into a hurricane.

As the ship rolled, the lifeboats were broken up and thrown into the foaming water by the furious waves. One lifeboat near the starboard paddle wheel was hanging from its davit and dancing about in a crazy fashion. It was damaging the paddle wheel, so Captain Walker had it cut away and ordered the starboard engines reversed to ensure the rejected boat did not harm the paddle further. The ship was wallowing and plunging at an angle of 45 degrees in the deep valleys of water, with overwhelming mountainous seas on either side. Walker was desperate to turn the ship into the wind, but before he could the paddle wheels were swept away by a huge wave.

Terrifying sounds were coming from the rudder, which had been twisted back by the heavy seas. It was out of control and was crashing rhythmically into the 36-ton propeller, which was somehow still turning. With the loss of steerage from the broken rudder it was quite impossible to turn the ship. And then the screw engines stopped. The ship was now without power and completely at the mercy of the elements. An attempt was made to hoist some sail, but the furious gale tore it to shreds.