По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

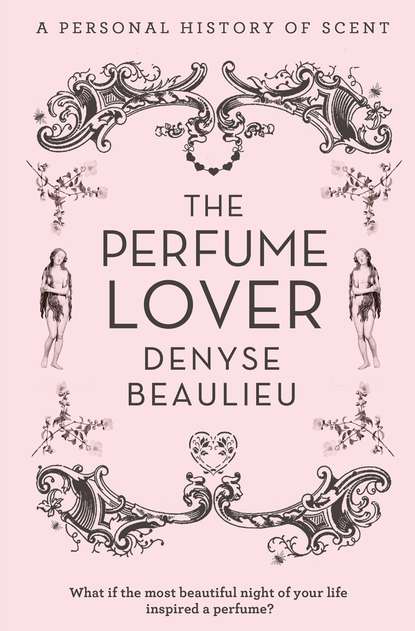

The Perfume Lover: A Personal Story of Scent

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I was eleven when I decided I’d be French one day. Not only French, but Parisian. And not only Parisian, but Left Bank Parisian: glamorous, intellectual and bohemian.

When she moved into the house next door with a German engineer husband, Geneviève didn’t quite replace The Avengers’ Mrs Emma Peel as my feminine ideal. Despite her closetful of clothes with Paris labels and her collection of French glossy magazines, Geneviève was still a housewife stuck in the suburbs of Montreal and even at eleven I knew I’d never be that. But when she opened that closet and those magazines, she drew me into a world where she herself had probably never lived. The world I live in now.

The scientific community is nothing if not international, but though my parents’ cocktail parties could have been local branch meetings of UNESCO, I’d never met a French person before. Next to Geneviève’s, my Quebec accent sounded distressingly rustic and I soon applied myself to mimicking her patterns of speech, which got me nicknamed ‘La française’ in the schoolyard. As soon as my homework was done I’d wiggle through a hole in the honeysuckle hedge and scratch at her back door.

Geneviève was in her late twenties, childless and homesick; she’d followed her husband as he was transferred from country to country, lugging a battery of Le Creuset pots and pans and a closetful of pastel dresses in swirly psychedelic or whimsical floral patterns which she’d happily model for me, and sometimes let me try on. I’d clack around in her pumps and twirl in front of the mirror. Sometimes we’d both dress up and stage make-believe photo shoots inspired by Vogue. Those were grand occasions since Geneviève would also let me pick from the array of cosmetics on her dressing table and carefully do my face. We’d model the looks in our very favourite makeup ads, the ones for Dior: pale, moody, smoky-eyed beauties with thin scarlet lips.

But there was one particular item on the dressing table I steered well clear of: a blue, black and silver-striped canister that said ‘Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche’. What if my lungs seized up? I hadn’t suffered an asthma attack since the age of six, but I’d witnessed my dad’s discomfort if we walked within ten feet of the perfume counters in the local shopping mall, so I wasn’t taking any chances. Geneviève gave a Gallic shrug when I finally, cringingly, explained about the allergies.

‘You North Americans really indulge your little bobos, don’t you? Here, look at this …’

She set her smouldering Camel in an ashtray, pulled out the scrapbook where she kept magazine cuttings and pointed to the picture of a slender young man with huge square glasses flanked by a lanky blonde in a safari jacket and a cat-eyed waif with a gypsy scarf on her head. The trio exuded a loose-limbed pop-star glamour. This was, Geneviève explained, Yves Saint Laurent, the greatest couturier in France, with his muses Betty Catroux and Loulou de la Falaise. And Rive Gauche was the perfume he’d named after his new boutique in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the first place she’d head for when she went back to Paris.

From the ads I’d spotted in my mother’s Good Homemaker magazine, I knew perfumes ought to have fancy glass bottles and evocative names like Je Reviens or Chantilly. There was nothing poetic about that metal canister. And Rive Gauche, what kind of a name was that? So Geneviève showed me the ad for Rive Gauche: a redhead in a black vinyl trench coat strolling by a café terrace with a knowing smile. Rive Gauche, plus qu’un comportement, it said; Rive Gauche, un parfum insolite, insolent. ‘More than an attitude. An unusual, insolent perfume.’

My friend explained about the Paris Left Bank, the jazz clubs and bohemian cafés on the boulevard Saint-Germain she used to walk by as a teenager to catch a glimpse of les philosophes, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. I’d read about Socrates in my children’s encyclopaedia but hadn’t fathomed that there were living philosophers or that they could even remotely be thought of as cool. At my age, cool was still a difficult concept to grasp.

‘Like pop stars, you mean?’

Geneviève nodded. Yves Saint Laurent, she went on, expressed the spirit of the Left Bank: youthful, rebellious and free. I couldn’t quite figure out how the soapy, rosy-green scent that clung to Geneviève’s clothes could reflect notions like youth, rebellion, freedom or insolence, and I had no idea of what constituted an ‘unusual’ fragrance. But I did half-guess from her wistful gaze that Geneviève, trapped in a Montreal suburb where there were no cafés haunted by chic bohemian philosophers or couturiers – there weren’t even any sidewalks! – longed for that lost world. A world captured in that blue, black and silver canister …

One afternoon, our orange school bus dropped us off early so that we could prepare for the year-end recital: I sang in the choir, humiliatingly tucked away in the last row with the boys because I’d suddenly grown taller than all the girls. Geneviève had promised that, for the occasion, she would do my hair up in her own signature style, a complex hive of curls fastened with bobby pins. I scrunched my eyes and held my breath as Geneviève stiffened her capillary edifice with spurts of Elnett hairspray.

‘There you go … Have a look!’ she said, waving a Vogue around to clear the fumes.

I opened my eyes to a chubby-cheeked version of Geneviève. The chignon was practically as high as my head: I’d tower over the boys too.

‘And now …’ Geneviève reached for her Rive Gauche. ‘As a special treat, I’ll let you wear my perfume … In France, an elegant young lady never goes out without fragrance.’

That spritz of Rive Gauche didn’t kill me; in fact, it made me feel better than I’d ever felt, so grown-up, so important – an eleven-year-old girl with the newest perfume from Paris! That’s when I resolved that when I grew up, I’d be like Geneviève, and never leave the house without a drop of perfume. And it would be French perfume, even if I had to swim across the Atlantic to get it.

4

What is it about the French and perfume? Draw up a list of the greatest perfumes in history. Shalimar, Mitsouko, N°5, Arpège, Femme, L’Air du Temps, Diorissimo? French. Study the top ten sellers in any given country. The labels may be American, Italian or Japanese, but the perfumers who composed them? At least half are French and most of the others are French-trained.

When Bourjois, the cosmetics company that owned Chanel perfumes, decided to put out a fragrance called Evening in Paris in 1928, they knew full well that they were launching the ultimate aspirational product. For millions of women, that midnight-blue bottle would hold the prestige and romance of the French capital within its flanks – it was the closest most would ever come to the Eiffel Tower. Judging from the number of Evening in Paris bottles that keep popping up on auction websites, they were right. For generations, ‘French perfume’ was the most desirable gift, short of mink and diamonds, and a lot more affordable.

But why is it that those two words, ‘French’ and ‘perfume’, have been said in the same breath for centuries? In other words: why is perfume French? If you ask most people in the industry, they’ll answer, ‘Well, because of Grasse, I guess,’ Grasse being the town in the South of France where perfumery developed as an offshoot of the leather-tanning industry. Tanning products were rank, so fine leathers were steeped in aromatic essences to counteract the stench, and Grasse enjoyed a particularly favourable microclimate for growing them. Though most of the land has now been sold to real-estate developers, it is still very much a perfumery centre, with several labs and a few prominent perfumers based in the area. But ‘Grasse’ doesn’t answer the question. There were other places in the world, like Italy and Spain, where a cornucopia of aromatic plants could be grown; where botanists, alchemists and apothecaries studied them, refined extraction processes, experimented with blends. There must be another reason why it was in France that perfume went from a smell-good recipe to liquid poetry; why it was here and nowhere else that modern perfumery was born, thrived and gained international prestige.

So why indeed? If anyone can answer the question I’ve been asking myself since I was eleven, it is the historian Elisabeth de Feydeau. We’ve just been enjoying an al fresco lunch in a garden gone wild with roses, lush with vegetal smells rising in the afternoon heat. A tall, chic blonde with a sweet, sexy-raspy voice, Elisabeth was formerly the head of cultural affairs at Chanel; she teaches at ISIPCA, the French school of perfumery, as well as acting as a consultant for several major houses; she wrote a book about Marie-Antoinette’s perfumer and a history of fragrance. So as we nibble on petal-coloured cupcakes, Elisabeth graciously shifts into teaching gear. I have indeed come to the right place for an answer, she tells me; the sacred union between France and fragrance was sealed right here where we’re sitting, in Versailles.

If Catherine de’ Medici hadn’t come to France in 1553 to marry the future King Henri II, perfume might well have been Italian. Not only did Italy enjoy a climate allowing the cultivation of the plants used in perfumery, but with Venice lording it over the sea routes, all the precious aromatic materials of the Orient flowed into the peninsula. And in the dazzlingly refined Italian courts of the Renaissance where the young Duchess Catherine was raised, perfume-making, intimately linked to alchemy, was a princely pastime practised by the likes of Cosimo di Medici, Catarina Sforza and Gabriella d’Este. Italian alchemists had started to divulge their methods of distillation and many of their perfumery treatises had already been translated. When Catherine de’ Medici arrived with her perfumer Renato Bianco in tow, she brought along the Italian tradition in all its refinement.

The French perfume industry was centred in Montpellier, where research on aromatic substances and distillation was carried out at the faculty of medicine (one of the oldest in the world, founded in 1220), and in Grasse, where skins imported from Spain, Italy and the Levant were treated. Up to then, perfumery had remained a subsidiary activity for apothecaries and tanners. Spurred on by the Italian fashion for scented clothes, leather items, pomanders and sachets, it developed into a luxury trade.

But the true turning point came from the scent-crazed king who had determined to transform his court into the crucible of elegance: it was under the reign of Louis XIV (1638–1715) that the French luxury industries acquired the excellence and prestige they still boast today. And that spectacularly successful marketing operation was a very deliberate political endeavour … During his mother Anne of Austria’s regency the young king had lived through the War of the Fronde, an uprising of the nobility that had threatened the very existence of the monarchy. To keep his noblemen under control, Louis XIV decided to move his court away from Paris to the newly built Versailles. There, he transformed his most trivial activities – getting out of bed, being groomed and dressed and even using the ‘pierced chair’ (the 17th century version of the toilet, known in England as ‘The French Courtesy’) – into a series of ritual displays which courtiers had to attend to curry favour with the monarch. By compelling them to follow the fashions he launched and to participate in the court’s lavish spectacles, the Sun King made sure they had no time or money to plot against the Crown. To imitate him, courtiers turned their toilette (named after the toile, the piece of cloth onto which cosmetics were spread out) into a social occasion. Celebrity endorsement was invented in Versailles. If, say, the king’s current favourite used some new pomade or scented powder in front of her coterie, she might create a stampede for it. This bit of information would be carried by a brand-new medium, the fashion gazette.

This was the other reason behind Louis XIV’s marketing operation. Fashion would radiate from his royal person to his court, from the court to Paris, and from Paris to the entire world, which would draw much-needed currency into the kingdom. His minister of finance Jean-Baptiste Colbert therefore set out to build up the French luxury industry, sending spies abroad to steal trade secrets and poach skilled artisans, and finding out which professional corporations were likely to become economic forces for France. Colbert made a deal with the guilds: they would be granted privileges and exempted from certain taxes provided they came up with the best and the most beautiful products. ‘The château of Versailles became, quite literally, a showroom designed to display the know-how of French craftsmen to foreign monarchs and dignitaries. There was an order book when you came out!’ chuckles Elisabeth de Feydeau. Paris, with its fancy shops staffed by well-turned-out young women, glittering cafés and public gardens, became an extension of that Versailles showroom, spurring on further demand for made-in-France luxury items, which in turn spurred on creativity, as perfumers refined their art to meet the exacting tastes of their snobbish clientele.

The perfume and cosmetics industry was one of those encouraged by Colbert. He boosted its profitability by setting up the Company of the Eastern Indies to ensure the supply of exotic ingredients while plantations were developed in Grasse. Again, Louis XIV provided the best possible celebrity endorsement: his orange blossom water, which came from the trees in the Versailles orangery, was exported all over the world. It was the only perfume the Sun King tolerated in his later years: in the last decade of his reign, perfumes gave him migraines and fainting spells which may have been psychosomatic, or due to allergies. ‘No man ever loved scents as much, or feared them as much after having abused of them’, wrote the memoirist Saint-Simon.

In fact, the royal scent-phobia just about killed the industry. A Sicilian traveller noted that ‘foreigners enjoy in Paris all the pleasures which can flatter the senses, except smell. As the king does not like scents, everyone feels obliged to hate them; ladies affect to faint at the sight of a flower.’ And indeed, though Versailles and Paris reverted to their old fragrant ways under the gallant reign of Louis XV, one of the most groundbreaking products in the history of the industry came not from Grasse, Montpellier or Paris, but from Italy via Cologne, Germany, where Johann Maria Farina launched his Aqua Mirabilis. The ‘Miraculous Water’, a light, bracing blend of citrus, aromatic herbs and floral notes in an alcoholic solution, is known to this day as ‘eau de Cologne’. This new style of perfumery, a departure from the heavy, animal notes used by Louis XV’s libertine court, was well in tune with the tentative progress of personal hygiene practices and the tremendously fashionable back-to-nature philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Noses and sentiments were becoming more delicate …

As Rousseauism swept through Europe, clothing, interiors, gardens and fragrances took on the tender floral tones that most flattered the fresh complexion of the kingdom’s premier fashionista, Queen Marie-Antoinette. It was under her reign that Paris consolidated its status as the trend-setting capital of the world. By the time her husband Louis XVI was crowned in 1774, the rigid etiquette of Versailles set up by the Sun King had lapsed and, as a consequence, the status of the aristocracy was rather less exalted than it had been. To stay ahead of the rising bourgeois class, the ladies of the court, led by Marie-Antoinette, resorted to the only thing that could keep them one step ahead of the commoners, however wealthy they were: fashion. In fact, this is how fashion as we know it – the latest trend adopted by a happy few for a season before trickling down to the middle classes – came into existence. Marie-Antoinette plotted the newest styles with her ‘Minister of Fashion’, Rose Bertin. She and her entourage would retain exclusivity for a set period, after which the item could be sold in Bertin’s Paris shop, Le Grand Mogol, and every woman who could afford it could dress herself ‘à la reine’. This, in itself, was a revolutionary move. As Elisabeth de Feydeau explains it, etiquette demanded that the Queen use Versailles suppliers. But Marie-Antoinette wanted her suppliers to go on living in Paris to sniff out the zeitgeist. Louis XIV had established the prestige of the French luxury trades, ‘but that little twist you can only find in Paris, that je ne sais quoi that makes Parisian women incomparable – and this comes out very clearly in the writings of foreign visitors of the period – emerges in the 18th century. There is a word that sums this up: elegance.’

With her gracious manners and lively laugh, Elisabeth herself is the very type of Parisienne foreign visitors have admired since Marie-Antoinette’s day. Even the dishevelled garden where we converse has just a touch of the négligence étudiée that distinguishes chic Parisian women from their fiercely put-together New Yorker or Milanese counterparts. I can easily envision Madame de Feydeau in one of the supple white muslin gowns the queen made fashionable in the 1770s, presiding over an assembly of philosophers and artists with whom she could match wits. Because this is what Paris gave to the world, through the learned, elegant women who led its social life and were deemed worthy intellectual sparring partners by the brightest men of the age: wit rather than pedantry; a way of thinking of life’s pleasures with the finely honed weapons of philosophy. You’ve always wondered why the French appreciate smart women? Why women don’t drop off the radar after the age of forty? There you have it. Where the art de vivre is a serious pursuit, the women who have turned it into an art form are valued indeed. And this, we owe to the 18th century.

Thus, it isn’t surprising that Elisabeth turned her attention to that very period with A Scented Palace: The Secret History of Marie-Antoinette’s Perfumer. Jean-Louis Fargeon rose to the top of his profession just as perfumery was severing its ties with tannery and glove-making to become a fully fledged trade – another turning point in the history of the industry. If he left his native Montpellier, it was because he knew that he could only succeed if he breathed in the incomparable esprit de Paris. And if he nabbed the world’s most prestigious customer, it was because he was incomparably skilled at composing the delicate floral blends that reflected the era’s craving for a simpler, more natural life … Fargeon’s status as the queen’s perfumer almost cost him his head during the French Revolution: he escaped the guillotine by a hair’s breadth simply because, as he was rotting in jail, Robespierre was executed, thus ending the Terror that cost the lives of over forty thousand people, a full third of whom were craftsmen. And the Revolution did, in fact, almost kill off the French perfume industry, not only because it dissolved the guild of perfumers, which reeked of aristocratic privilege, but because most of its clients were either beheaded or exiled. By the time a new court was formed around the Emperor Napoleon, tastes had changed. Though the Empress Josephine was inordinately fond of musk, he preferred her natural aroma, famously asking her not to wash for several days because he was returning from a military campaign. And he loathed perfume apart from eau de Cologne, which he carried everywhere with him, literally showered with and even consumed by dunking lumps of sugar in it. After his fall, the French luxury trades declined while the English industry gained ascendancy.

‘Then, in 1830, French perfumers came up with the phrase “Invent or perish”,’ reveals Elisabeth. ‘They realized that the world had changed, that the perfumery of the old regime was no longer possible, and from 1840 onwards, French perfumery started rebuilding itself.’

But the period was dominated by bourgeois, puritanical values, and vehemently rejected the wastefulness and deceit of cosmetics and fragrances. ‘Perfumes are no longer fashionable,’ sniffed a French Emily Post in 1838. ‘They were unhealthy and unsuitable for women for they attracted attention.’ At most, a virtuous woman could smell of flowers, and not just any flowers: heliotrope, lilac, carnations or the whitest possible roses. Master perfumers like the Guerlains – the house was founded in 1828 – undoubtedly made lovely blends for their wealthy customers, but the bulk of scents were mainly used as personal hygiene products in an era when most homes didn’t have running water. Fragrance was no longer a luxury: it was just a way of smelling nice, of removing bad smells.

Paris, however, remained the capital of fashion: it was here that the Englishman Charles Frederick Worth established himself as the world’s first star couturier, under the reign of Napoleon III. But French perfumery would have lagged behind without the handful of visionaries who propelled it into the 20th century.

One of these men was Jacques Guerlain, who authored a series of shimmering, impressionistic masterpieces still produced and adored to this day: Après l’Ondée, L’Heure Bleue, Mitsouko and Shalimar. But an upstart was hot on his heels, a self-taught perfumer untrammelled by tradition and therefore willing to use the new, more brutal synthetic materials to conjure vibrant Fauvist compositions in tune with the scandalous Ballets Russes. It was the Corsican François Coty, known as the Napoleon of perfumery, who democratized fine fragrances by launching cheaper ancillary lines, whereas Guerlain perfumes were still sold to a very select clientele. Soon, he was selling 16 million boxes of talcum scented with L’Origan in France alone. Guerlain had reinvented the heritage of traditional perfumery: Coty turned it into a worldwide industry and took it into the 20th century.

But it was haute couture that truly transmogrified Paris perfumes into the stuff dreams were made of for millions of women around the planet – the stuff that would make a young girl in the suburbs of Montreal decide she would be Parisian one day because of a spritz of Rive Gauche. ‘As long as you’re in a one-to-one relationship with your customer, like Jean-Louis Fargeon was with Marie-Antoinette, or Jacques Guerlain with the clients who came to his salon, you can explain your perfume, make it loved,’ Elisabeth tells me. ‘But when fragrance becomes an industry, how do you sell it as a luxury item? Perfume needs to be supported by image. And who but world-famous Paris couturiers could provide a better one?’

The first couturier to launch a perfume house was Paul Poiret, in 1911. The Pasha of Paris, as he was dubbed, was practically the first to turn fragrance into a concept, with a dedicated bottle and box for each product. But he made the marketing mistake of not giving it his own name. The first to do that, in 1919, was Maurice Babani, who specialized in Oriental-style fashions and whose perfumes bore such exotic names as Ambre de Delhi, Afghani or Saigon. Gabrielle Chanel followed suit in 1921, but her N°5 only went into wider production in 1925, when she partnered up with the Wertheimers who owned Bourjois cosmetics. By that time, other couturiers like Jeanne Lanvin and Jean Patou had realized perfume was a juicy source of profit and got in on the game. Thus it was that in the first decades of the 20th century, French couture and perfumery began an association from which the prestige of the most portable of luxury goods – a few drops on a wrist or behind the ear – would durably benefit.

But it wasn’t all a canny exploitation of the Parisian myth. French perfumery truly was the best and the most innovative; French perfumers did create most of the templates from which modern perfumery arose. Why? Perhaps because, ever since Colbert’s day, Paris had been a laboratory of taste, not only in fashion or perfume, but also in cuisine and decoration. A discerning clientele of early adopters, eager to discover new styles and new fashions, spurred the purveyors of luxury goods into devising ever more refined, more surprising, more delightful products, thus bringing their craft to an incomparable degree of perfection. Function, as it were, created the organ. In this case: the best noses in the world.

5

However, my very first perfume was not French, but American. Its frosted apple-shaped bottle has managed to survive the decades without getting carried off in my mother’s garage sales. It followed my parents when they sold the house where I grew up. It still taunts me whenever I go home to visit …

Geneviève certainly meant well when she picked Max Factor’s Green Apple for me as a parting gift before she followed her husband to Saskatchewan. She must have been told it was suitable for young girls. I hated it. Unlike Rive Gauche, which had given me a glimpse of the woman I aspired to become, Green Apple didn’t tell a story. Or if it did, it was a story I didn’t want to hear in my first year in high school; a story that contradicted my training bra and the white elastic band that had already cut twice into my budding hips, holding up Kotex Soft Impression (‘Be a question. Be an answer. Be a beautiful story. But be sure.’) What it said was: ‘Don’t grow up.’

Wear Green Apple: He’ll bite, insinuated the Max Factor ad. Never mind that apple candy has never registered as a powerful male attractant and that I’d never been kissed by a ‘he’, much less bitten. I’d attended Sister Aline’s catechism class and I got the Garden of Eden reference behind that slogan, thank you. But to me, that bottle wasn’t the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. It was Snow White’s poison apple. And an unripe one at that, just like me. The only apple-shaped things I wanted to own were starting to fill my A-cups.

When the good people at Max Factor put out their apple-shaped bottle, conjuring memories of Original Sin and of the Brother Grimms’ oedipal coming-of-age tale, they tapped into a symbolic association which Dior would later fully exploit with another potion in an apple. But that one would be called Poison: the myth of the femme fatale poured into amethyst glass and wrapped in a moiré emerald box – purple and green themselves hinting at venom and witchcraft …

When it was launched in 1985, I’d long grown out of my Green Apple trauma and into the twin addictions of ink (usually purple) and perfume. I hoped to become a writer, and a fragrant one at that. I’d just finished writing my Masters dissertation on 18th century literature and I was struggling through my first academic publication in France, an essay on Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, when I stumbled on an article about Poison, ‘a spicy perfume blending Malaysian pepper, ambergris, orange blossom honey and wild berries’. This was particularly serendipitous: the whole point of my essay was that the adulterous Emma Bovary’s aspiration to become a romantic heroine despite the mediocrity of her provincial surroundings was the result of her mind being poisoned by cheap romantic novels. A farmer’s daughter married off to a small-town doctor, she grew so frustrated at not being able to live out her girlhood fantasies that ‘she wanted to die. And she wanted to live in Paris.’ Emma never got closer to Paris than Rouen but she managed to run up such a debt with the local frippery pedlar that her house and belongings had to be auctioned off, whereupon she poisoned herself with arsenic. In my essay, I contended that the ink she had absorbed when reading romances had poisoned her every bit as much as the rat-killer.

‘What I blame [women] for especially is their need for poetization,’ Flaubert wrote in 1852 to his lover Louise Colet. ‘Their common disease is to ask oranges from apple trees … They mistake their ass for their heart and think the moon was made to light their boudoir.’ As neat a forecast as ever was of what would drive perfume advertising one century hence. Weren’t we all modern embodiments of Emma Bovary, I thought, seeking magic potions to transform our lives? To die or live in Paris … And now, a legendary couture house where a latter-day Bovary could well burn through her husband’s earnings was selling an intoxicating – and perhaps toxic – dream of romance and glamour under the slogan ‘Poison is my Potion.’

When the CEO of Christian Dior Parfums, Maurice Roger, first decided, in 1982, to launch Poison, the industry had been undergoing deep mutations. Perfume houses were being bought up by multinational companies, and their new products had to have global appeal. With the blockbusting, take-no-prisoners Giorgio Beverly Hills, America was starting to bite into a market that had hitherto been dominated by France. To make itself heard around the world in the brash, loud, money-driven 80s, the house of Dior had to create a shock. This, Maurice Roger knew, meant renouncing the variations on the name ‘Dior’ which had been used to christen all their feminine fragrances from the 1947 Miss Dior to the 1979 Dioressence; it meant foregoing Parisian ‘good taste’ and striking with an unprecedentedly powerful scent and concept. It meant re-injecting magic, mystery and a touch of evil into something that was no longer for ‘special moments’ (think of that fragrance your grandmother kept on her dressing table and only dabbed on when she pulled out the mink and pearls), no longer a scent to which women were wedded for life, but a consumer product. The magic, this time, would be entirely marketing-driven, though the fragrance itself, selected out of eight hundred initial proposals, required over seven hundred modifications before reaching its final form.

The promotional campaign kicked off with a ‘Poison Ball’ for 800 guests at the castle of Vaux-le-Vicomte hosted by the French film star Isabelle Adjani. And, if the bottle was reminiscent of the story of Snow White, the advertising film conjured another fairy tale, The Beauty and the Beast. Its director, Claude Chabrol, never hinted that the would-be femme fatale might be the one to succumb, Bovary-style, to the potion it touted. But I’m sure Chabrol, who would go on to direct an adaptation of Madame Bovary, had a thought for one of his film heroines, the eponymous and fragrantly named Violette Nozière, a young prostitute found guilty of poisoning her parents in 1934 (both characters played by the exquisitely venomous Isabelle Huppert).

‘Who would offer someone a gift of poison?’ the New York Times fashion editor wailed. And Dior’s blockbuster did, in fact, wreak havoc in its wake. Innocent bystanders complained of headaches and dizziness; diners were put off their food by its near-toxic intensity. It was banned in some American restaurants, where signs read ‘No Smoking. No Poison.’

Perfume is an ambiguous object, forever hovering on the edge of stink: what smells suave to me can be noxious to you, and the padded-shouldered juices of the 80s gave the first ammunition to the anti-perfume movement. Google ‘perfume + poison’ today and you’re just as likely to find entries about Dior as exposés on the purported toxicity of fragrance. Perfume aversion is no longer fuelled by the strength of the smell of perfume but by fear of the invisible chemicals that might be infiltrating our bodies through our skin and lungs. Activist groups have been flooding the internet with ominous warnings about ‘unlisted ingredients’ which sound as if they belong in some mad scientist’s lethal cocktail and would be enough to put off anyone but the staunchest fragrance aficionado. And since perfume, unlike anthrax, radiation, or the toxins in building materials, food and water, is both perceptible and dispensable, it’s crystallized a rampant paranoia. If you start obsessing that the woman in the next cubicle is poisoning you with her Obsession, at least you can do something about it: file a lawsuit.

But the fear of smells itself, brilliantly explored by the French historian Alain Corbin in his 1982 classic The Foul and the Fragrant, goes back millennia. Until the link between germs and disease was established in the late 19th century, people were convinced smells could kill. As far back as the 5th century AD, physicians were accusing foul odours of causing plagues. Since nobody knew how illnesses spread, it seemed logical to suspect the airborne stench rising from graveyards, charnels, open cesspools or stinky swamps. And no less logical to suppose that the stench, and hence the disease it carried, could be repelled by another, stronger smell. Aromatic materials were not only considered salubrious because of their medicinal properties: they were also believed to be the very opposite of the corruptible animal and vegetal matters whose putrescence was thought to cause disease. In fact, they were just about as pure as earthly matter could be, since aromatic resins burned without residue, and essential oils were the volatile spirit that remained after the distillation of plants. Those very same aromatic materials were used to prevent corpses from putrefying. Could they not prevent the corruption of the living body by disease as well?

So ‘plague doctors’ stuffed them in beak-shaped masks as they made their rounds during epidemics of the Black Death; aromatic materials were burned in houses, churches, streets and hospitals. And if the wealthy lavishly scented their clothes and held pomanders to their noses, it wasn’t only to cover up the effluvia of the great unwashed or the stench of cities and palaces: scent was their invisible armour against the Reaper. In fact, if everyone from kings to paupers did give off quite a pungent aroma from the late 15th century, when public baths were shut down for moral reasons (they often harboured prostitutes), until the late 18th century, it was precisely because foul miasmas were believed to carry disease. Physicians were convinced that water distended the fibres of the body, leaving it wide open to airborne contamination. Therefore, bathing was undertaken only under strict medical supervision, and people who’d just bathed were advised to stay under wraps for hours, if not days, until their bodies had sufficiently recovered to withstand exposure. Such cleanliness as there was came from washing face, teeth and hands with various cosmetic preparations; bodily grime was meant to be absorbed by white linen shirts, which only the upper classes could afford to change daily.