По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

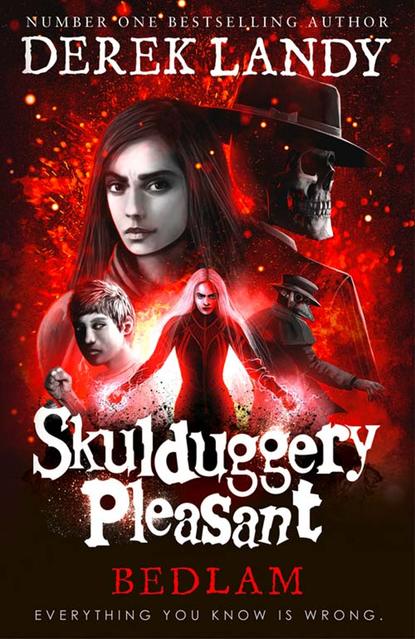

Bedlam

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“A cat,” the aide repeated. Flanery didn’t know his name. Aides’ names were rarely important. “Or a dog. A pet, basically. We feel it might soften your image.”

“What’s wrong with my image?”

The aide paled. “Nothing.”

Flanery leaned forward, elbows on his desk. “Then why do I need to soften it?”

The aide looked around for help. None came. That pleased Flanery. He liked to see people flounder.

“We just thought,” the aide said, not nearly so confident now, “that it might be a good idea to present a, uh, a more relatable image to the voters.”

“They seemed to relate to me fine when they voted for me,” Flanery said. “You think they’ve forgotten that? You think they’ve forgotten who I am?”

“I … I didn’t mean anything by it, sir.”

“You know your problem? The lot of you? You’re approaching it all wrong. People don’t want to relate to me. They want to emulate me. They want to be me. I offer them what nobody else does. I offer them glamour. Celebrity. I offer them opulence, and that’s what they want. When they’re paying for groceries or standing in line for a hot dog or watching the game, they think about me and they know that if they put in the time and the effort, they could have what I have.”

This was a lie, of course. In order to have what Flanery had, they’d need his money and his keen understanding of power, a talent that allowed him to take risks that the average person couldn’t even begin to comprehend. He was so far beyond them that it had stopped being funny a long time ago – but the fantasy seemed to keep them happy.

The conversation turned to matters of policy, and Flanery’s mind drifted to Dan Tucker, the vice-president, and the interview he’d given that made it sound like he was mocking Flanery’s intelligence. Flanery would have to talk to him about that. Or get his Chief of Staff to talk to him. He was sure it had just been a mistake. It had to have been.

Then he thought about the Big Plan that he’d come up with, and he thought about Abyssinia and about how much he despised her. She was a witch, and she treated him with disrespect. Because of that, he didn’t like talking to her. He quite enjoyed it when she rang his private phone and he didn’t answer. That was a power move. His father had taught him all about power moves, and Flanery had added a few of his own over the years. He was an expert at power moves.

When the meeting was done, he dismissed them all and left the Oval Office. He went down the corridor and kept going until he entered the Residence. He went into the dining room and shut the door, then turned on the TV to find out what the press was saying about this whole Dan Tucker mess.

It was not good.

“Everything OK, Martin?”

Flanery yelled and jumped. Crepuscular Vies sat at the table, halfway through a meal. His shirtsleeves were rolled up and he wasn’t wearing his hat. His bow tie had butterflies on it.

Flanery didn’t like to see him eating. Having no lips made it unpleasant. “How did you get that food?” he asked, looking away.

“I picked up the phone and ordered it,” Crepuscular answered, and then, in a startlingly precise impression of Flanery’s own voice, said, “Bring me a steak, fried to a crisp, with some fries. No vegetables.’ You’re not a difficult man to impersonate, Martin, even though I was restricted to the terrible orders you regularly make. Steak, well done? That’s a crime against cattle.”

With no idea how to respond to that, Flanery decided to let it go. To cover up this momentary weakness, he jabbed a finger at the TV. “You hear this crap? You hear what they’re saying?”

Crepuscular sawed through another bit of meat, then popped it between his teeth. “I did.”

“They’re saying Tucker insulted me,” Flanery said, feeling the anger rise again. “They’re saying he called me stupid. He’s the vice-president! He wouldn’t do that. I’m the one in charge. He wouldn’t be vice-president if it wasn’t for me picking his name out of a hat!”

“You might not want to tell him that part.”

“You’re supposed to help me,” Flanery grumbled. “Isn’t that what you said you’d do? Isn’t that what you promised?”

Crepuscular didn’t say anything. Good. That meant Flanery had him on the back foot. Not responding to a challenge showed weakness, which was why Flanery always responded to opponents with insults or scorn. Crepuscular, for all his arrogance, hadn’t learned that yet.

“As far as I can see,” Flanery continued, “you haven’t lived up to your part of the deal. This shouldn’t be happening. The media shouldn’t be reporting this stuff. What are you going to do about it? I get enough incompetence with my staff, I do not need it from you!”

Flanery stopped, and waited for Crepuscular to respond.

Crepuscular finished eating, and dabbed at his lipless mouth with a napkin before he stood. He pushed the chair back into place and unfolded his shirtsleeves, buttoning them at the wrist as he came forward. He reached out and his hand closed round Flanery’s throat and he walked him backwards.

“You seem to be mistaking me for someone else,” Crepuscular said.

Flanery wasn’t a particularly athletic man, and he’d never played sport or learned how to box or wrestle, and in many respects he’d never had to actually lift anything heavy in his life, but even so he was surprised at the ease with which Crepuscular pinned him to the wall. His height, his weight, his importance – none of it meant anything. To Crepuscular, Flanery was nothing but a weakling.

“You seem to be mistaking me for Mr Wilkes,” Crepuscular continued. “He was the one you barked at, and complained to, and insulted. He was the one who scurried after you. Do you think I’m him, Martin? Is that what you think?”

Flanery tried to answer, but all he could do was gurgle. He could barely shake his head.

“I’m the one who killed him, Martin,” Crepuscular said. “I’m the one who snapped his neck after he’d finally had enough. I remember the look on your face when he stood up to you. Your bullying didn’t seem to work on him then, did it?”

Darkness clouded Flanery’s vision. He was aware of his own spittle on his chin. He was aware of the ridiculous sounds he was making. He was aware of his hands, tapping weakly against the scary man’s arm. His head pounded. His legs were jelly.

And then Crepuscular moved him away from the wall and swung him round, and the backs of his knees hit something and he collapsed into a chair and Crepuscular was walking away.

Flanery doubled over, gasping for air.

“You’re doing a great job, Mr President,” Crepuscular said, his voice coming from somewhere behind the drumming of Flanery’s own heartbeat. “Don’t let the liberal media get you down. They don’t understand you. They don’t see why the people love you. And they do love you. More than any other president since Lincoln.”

Nodding, Flanery straightened up in his chair.

Crepuscular had put his jacket on. He was wearing another one of those checked suits he liked so much. He put on his hat and straightened his bow tie. “Ten days,” he said. “Ten days and your plan goes into action. Ten days and the world changes, sir, and you go down in history. Are you looking forward to that?”

Flanery nodded quickly.

“Then who cares what they say on the news? And who cares what Vice-President Tucker may or may not have called you? None of it matters. The only thing that will matter, in ten days’ time, is the small naval base in Whitley, Oregon, and all the people who died there.”

(#ulink_75f8dc02-8f84-5328-81ac-d7ddd1c001d8)

It was a messy business, crying.

Sebastian hated it. His tears would fog up the lenses on his mask and his face would get all wet and dribbly and there wasn’t anything he could do about it except wait. Eventually, the mask would soak it all up, just like it did when he perspired. Or sneezed.

Sneezing was the worst. Well, sneezing was the worst so far. Every night, before he went to sleep, he prayed that there would be no reason for him to throw up the next day.

His suit. God, he hated that thing. The beaked mask that made him look like a crow. The heavy coat. The hat. Why was there even a hat? Why was the hat necessary?

He hated it all. He longed to touch his own skin, to rake his fingers through his hair. Ever since he’d put the suit on, he’d been unable to scratch himself. Itches drove him mad.

And breathing. Oh, how he missed fresh air. How he missed the taste of it. And the feel of it. A breeze. What he wouldn’t give to feel the slightest breeze against his face.

But the worst thing about this whole mission was the loneliness. The sheer, terrifying loneliness of his situation. Every other day, he’d get an update on the continuing search for Darquesse. He’d stand there and nod while Forby took him through the details of what he was doing, pretending to grasp at least some of the fundamentals when it came to scanning an infinite number of dimensions for the slightest trace of Darquesse’s energy signature. He was sure Forby now regarded him as an idiot, and probably regretted voting for him to be the leader of their little group, but for Sebastian it was one of the few chances he got to interact with a real live person, so he loved it. He loved every mind-numbingly confusing second of it.

And, every week, they’d have their meeting. They’d all get together at Bennet’s, or Lily’s, or Kimora’s. Never at Ulysses’s house, because his wife didn’t approve, and never at Tarry’s, because he said his place was always a dump, but they got together and they chatted and either Ulysses or Lily would bring cake, and even though Sebastian didn’t need food – his suit took care of his nourishment – and he couldn’t eat even if he wanted to, it was good. He had friends.

But then the meeting would end, and they’d all head back to their families and to their lives, and Sebastian would return to the empty house he’d made his own, and sit there. In the dark. In the silence.