По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

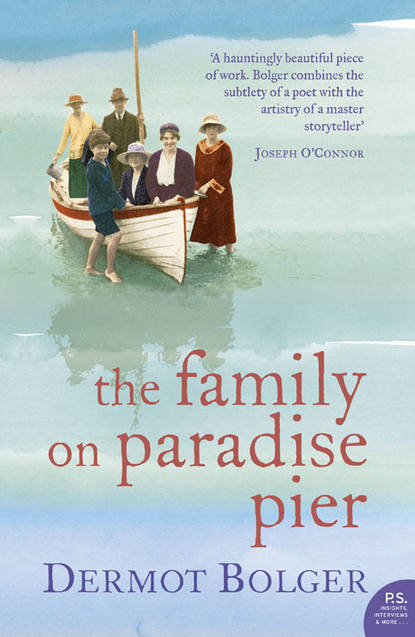

The Family on Paradise Pier

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That’s how life is ordained.’ Mrs Hawkins broke into a verse of All Things Bright and Beautiful:

‘The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

He made them high or lowly

And ordered their estate.’

‘Stop the cart,’ Art said with sudden fierceness. ‘He’s my size. I want to give him these shoes. It’s stupid that I own five pairs and he has none.’

Pappy laughed, wrapping Art in a bear-hug till the boy ceased to struggle.

‘You’re a good boy, but you must harden yourself or be fooled by every beggar and three-card-trick-man on the street. He’ll have shoes when he earns them. It’s how the world works. You’ll have men under you one day. Firm but fair is how to win respect, not by throwing away your possessions.’

Distant laughter rose behind them as Father joked with the boy who managed to harry the sheep into an enclosure. Brendan was asleep, being rocked on Mother’s lap. Eva envied Art his place on Grandpappy’s knee, like she envied him the status she would have enjoyed if born a boy. Art was her special friend, but since Beatrice Hawkins started talking too much or going silent in his company, Eva had been disturbed by a recurring dream. In it Art was bound in a dungeon with Eva advancing on him, holding the terrible steel contraption she once saw a farm boy carry. When Eva had asked what it was the boy snapped it shut and smirked, ‘To castrate young bulls, miss, and put a halt to their jollies.’ Eva did not know what castration meant until Maud, who knew everything, said it was ‘to cut off the slip of a thing men make such a fuss about’. This dream mortified her because she could never hurt Art. Shivering, Eva reached guiltily across to ruffle Art’s hair. He loosened Grandpappy’s bear-grip enough to smile back, although she saw how he was still upset.

Dunkineely village was deserted when the pony cantered past MacShane’s public house. Mr MacShane emerged and said that a shoal of mackerel had swum into the inlet at the Bunlacky jetty. Grandpappy whipped the pony so as not to miss the excitement. The lane was crammed, with people lining the rocks beside the tiny jetty as the trap came to a halt. Youths had only to cast fishing rods in the waves to instantly haul out more silvery bodies. Women waded into the water using turf creels to capture the fish battering senselessly against each other. Barefoot children outdid one another in savage bravado as they killed the gasping fish with stones. Grandpappy laughed with approval, urging Art to dismount. Eva watched her brother join in the orgy of slaughter, blood and fragments of gut staining his shirt. The air was festive, pierced by warlike shouts of Take that, you Hun. Finally the aeroplane cart arrived and Beatrice Hawkins watched Art spatter a mackerel’s brains with as much admiration as if he were harpooning a whale. Father noticed Eva sitting very still beside Mrs Hawkins. ‘Run along home,’ he said quietly, ‘and tell Cook we’re having mackerel for supper. I’m sure the Hawkinses can be prevailed upon to stay. Aye, and tell her we’ll be having mackerel for breakfast, lunch and dinner all next week too.’

Eva had seen Art fish with Father and even helped them to kill sea trout out on their small boat. Sea fishing had felt noble but now she couldn’t bear to look back in case she saw Art hold up the dead mackerel amid the slaughter for Beatrice to admire. Eva ran home to give Cook the message, then went to her room. Her perfect day in paradise felt ruined. Pressing her face against the cool sheet on her bed, Eva closed her eyes but kept visualising a floundering shoal of mackerel. They refused to die, wriggling furiously with their battered heads. Fish eyes stared up, having got separated from scaly bodies. They became the eyes of dead soldiers in the war that Eva hated people discussing. She had always loved the taste of mackerel but knew that she could never bear to bite into their oily flesh again.

Maud entered the room, kicked off her shoes and threw her hat on her bed. She flopped down. ‘Come on, Eva,’ she said. ‘The Hawkins girls are staying and Mother says we can play musical bumps. Surely there’s some way to persuade Oliver to join in. My word, it has been such a day.’ She stopped and looked across. ‘What’s wrong, Eva?’

‘Nothing.’

‘You look like you’ve been crying.’

‘Haven’t.’

‘Cook says we’ll have a feast.’

‘What is she making?’

‘Fish, you goose. Get changed. It will be such fun. Father says we can use the gramophone.’ She sat up to observe Eva closely. ‘Shall I call Mother?’

‘I’m all right.’

‘I think I will.’

Maud went out, leaving the door open. Rising, Eva poured water into the white basin to wipe the smudge of tears from her eyes, then walked towards the window overlooking the street. The carpet ended a few feet from the window, the floorboards cool on her soles. The windowpane soothed her forehead. She felt so small suddenly in that long room, imagining the lonely winter months of solitary lessons ahead. Sketching for hours by the Bunlacky shore, reading to Brendan or sitting with Mother while she read books of sermons sent from London. Each Tuesday Mother would engage in planchette with her psychic friend, Mrs O’Hare – both women calmly attempting to decipher spirit messages, with the table moving beneath their outspread hands. But despite such loneliness it was better than the horrors of the bustling school dormitories to which the others would return.

A sound betrayed Mother’s presence.

‘What’s wrong, Eva?’

‘Nothing.’

‘That’s not true. Normally you would be the first downstairs on such an evening. We don’t have secrets, you and I.’

‘It’s too terrible.’

‘Nothing is terrible if you share it.’

Eva meant to describe the mackerel, but the streaks of blood on Art’s shirt on the jetty became confused with his tortured body in her dream. ‘I keep having nightmares where I hurt Art terribly. I must be the worst sister in the world.’

Mother stood behind Eva who was unable to turn and face her. The woman did not place a hand on her shoulder but Eva sensed the comfort of her presence.

‘You’re a Virgo,’ Mother said calmly. ‘All Virgos have a touch of that. I’m to blame for telling you I wanted a boy before you were born. But your dream might not be about Art. It could be the memory of unfinished business from another life or a vision of something to come. And even if it is about Art we’re not to blame for our dreams or for being complex. You want life to be black and white, but we all have two sides. Just because we each hide one side from strangers doesn’t mean we should hide it from ourselves. Everyone is jealous. Look at me, crippled with arthritis. Some days I’m jealous of you dancing around, unaware of the wonder of being able to move without pain. You’re allowed to feel jealous, Eva. You’re allowed to be anything that’s part of you once it doesn’t take over. Now is your secret so terrible?’

‘Don’t tell Father.’

Mother laughed. ‘Us women need a few secrets, because God knows men keep enough. I’m jealous of your hair too. Let me comb it, then away downstairs. You need to be out more with other children. Maybe I’ve been wrong to keep you away from school. But you’ve always been so delicate that I was worried you might not cope.’

‘I don’t want to go to school,’ Eva said. ‘I love life here.’

‘You’re lonely in winter,’ Mother replied. ‘Still, it’s too lovely an evening for worries.’

She brushed Eva’s hair in comforting strokes, tilting her head slightly and smiling at Eva until her daughter smiled back. Eva looked around to spy Art in the doorway, concerned at her absence.

‘The fun is starting,’ he said, ‘but it’s not the same until you come down.’

Taking Eva’s hand, he drew her from the room. On the stairs they passed Nurse carrying Brendan who had woken up. The small boy put out his hand to Art, delighted when his big brother squeezed it. Eva looked back at Mother who smiled as she watched them descend towards the excited voices in the drawing room. Grandpappy had gone to rest but the other men were emerging from a pre-dinner drink in Father’s study. Eva noticed that Oliver had been allowed to join them.

‘Your AE is a menace with his anti-recruitment talk,’ Mr Hawkins was complaining. ‘It was bad enough him siding with Larkin’s union during the Dublin lockout two years ago. He would do better sticking to painting fairies than meddling in politics.’

‘AE is entitled to his opinion,’ Father replied. ‘Not that the King or Kaiser will pay him any more heed than the Dublin employers did. They were determined to break the workers and had the Roman church behind them.’

‘Your church too,’ Mr Hawkins pointed out. ‘Larkin is a communist. What support could AE gather for such a blackguard?’

Remembering Mother’s reference to AE, Eva imagined an army of stone figures rising from Dublin Bay, summoned by the bearded mystic whom Mother regarded as a friend.

‘What is a communist, Father?’ Art asked, alerting the men to their presence on the stairs.

‘A thief,’ Mr Hawkins retorted, ‘who would murder you in your bed and divide your possessions among every passing peasant.’

‘Somebody who thinks differently from us,’ Father interjected quietly.

‘True,’ Mr Ffrench agreed. ‘Perhaps Christ was a communist.’

‘Really, Ffrench!’ Mr Hawkins was aghast.

‘I don’t think he was,’ Father said. ‘Christ asked us to live selfless lives for love of our fellow man and the promise of our reward in the next life. The communist offers no such reward. His world will not work because we are the flawed children of Adam. The communist may proffer an earth without God, but he cannot create an earth without sin. Our chief sin is greed and that is the worm which would devour the communist’s clockwork world.’

‘Larkin would devour your world too,’ Mr Hawkins argued. ‘Hand in hand with the Germans, he would murder every Irishman of property, with your cousin acting as his scullery maid.’

‘Countess Markievicz knows her own mind,’ Father replied mildly.

‘She’s a traitor to her class,’ Mr Hawkins declared, ‘consorting with dockers and slum revolutionaries? Is this the mob you would put in power if we gave you Home Rule?’