По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

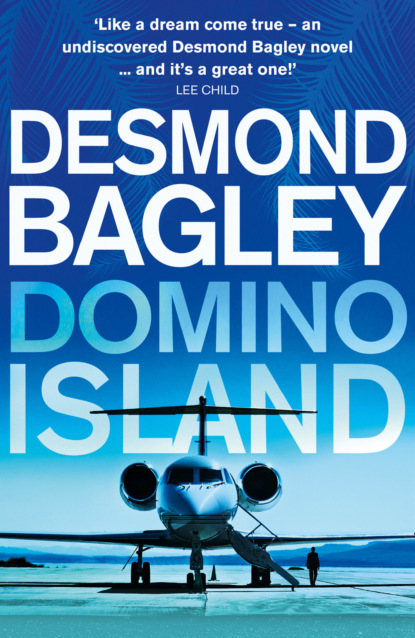

Domino Island: The unpublished thriller by the master of the genre

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What else but insurance? I’m a money man at heart.’

She smiled. ‘I doubt that. Are you married?’

‘Not at present.’

‘You sound as though you’ve been burned. You were married?’

I hooked over a chair with my foot and sat down. ‘Twice. My first wife died and my second divorced me.’

‘I’m sorry to hear about the first, and surprised at the second.’

‘Surprised?’

‘I can’t see how a woman in her right mind would let you get away.’

I thought she was joking but she seemed serious enough. Abruptly she put down her glass and walked across the kitchen to open the lid of a big deep freezer. I played it lightly and said to her back, ‘There was nothing to it. I didn’t wriggle off the hook – she threw me back.’

‘Why? Were you tomcatting?’

You ask some damn personal questions, Jill Salton, I thought, then reconsidered. Come to that, so did I. Perhaps this was her way of giving me a taste of my own medicine. ‘No,’ I said. ‘She didn’t like bigamy. I was married to the insurance industry.’

She took some packets to a counter and switched on an oven, then began to prepare the food. From what I could see, millionaires didn’t eat any better than the rest of us – just the same old frozen garbage. ‘Some women are fools,’ she said. ‘When I married David I knew what I was getting into. I knew he had his work and it would take up a lot of his time. But there’s a certain type of woman who doesn’t understand how important a man’s work can be to him.’ She paused with a knife upheld. ‘I suppose it means as much as having a baby does to a woman.’

‘You’re not the liberated feminist type, then. When were you married?’

‘Four years ago.’ She got busy with the knife. ‘Believe it or not, I was still a virgin at twenty-four.’

She was right – I did find it hard to believe. I wondered why the hell she was telling me all this. My acquaintanceship with beautiful young heiresses was admittedly limited, but I’d come across a handful in the way of business and none had felt impelled to tell me the more intimate details of her life. Still, statistically, anything can happen given a long enough period of time, and maybe she’d get around to telling me about the quarrel with her husband.

She said, ‘David was exactly twice as old as I was, give or take a couple of weeks. My family said it would never work.’

‘Did it?’

She turned her head and looked at me. ‘Oh yes, it worked. It worked marvellously. We were very happy.’ She looked down at the counter again and wielded the knife. ‘How was your first marriage?’

I looked back along the years. ‘Good,’ I said. ‘Very good.’

‘Tell me about her.’

‘Nothing much to tell. We married young. I was a second lieutenant and she was an army wife.’

‘So you were a soldier.’

‘Until ten years ago, when I started working with Western and Continental. I’m still in the reserves.’

‘What rank?’

‘Colonel.’

She raised her eyebrows. ‘You must have been good.’

I laughed. ‘Good, but not good enough, tactically speaking.’ I found myself telling her about it.

I had worked my way upwards from my green commission with a rapidity that pleased me until I found myself a half-colonel commanding a battalion in Germany. I did not get on very well with my superior officer, Brigadier Marston, and the bone of contention was that we disagreed on the role of the army. He was one of the old school, forever refighting World War II, and thought in terms of massed tank operations, parachute drops of entire divisions and all the rest of the junk that had been made obsolete by the pax atomica. For my part, I could see nothing in the future but an unending series of counter-insurgency operations such as in Malaya, Cyprus and Aden, and I argued – maybe a bit too forcibly – that the army lacked training for this particular tricky job.

When Marston wrote my annual report it turned out to be a beauty. There was nothing in it that was actionable; in fact, to the untrained eye the damned thing was laudatory. But to a hard-eyed general in the War House, skilled in the jargon of the old boys’ network, the report said that Lt-Col William Kemp was not the soldier to put your money on. So I was promoted to colonel and I cursed Marston with all my heart. A colonel in the army is a fifth wheel, a dogsbody shunted off into an administrative post. My own sideline was intelligence, something at which I was particularly skilled, but my heart wasn’t in it. After a couple of years I negotiated very good freelance terms with Western and Continental, who paid willingly for my expertise. I would still be pushing pieces of paper around various desks but I’d be getting £15,000 a year for doing it. Marston, meanwhile, was in Northern Ireland, up to his armpits in IRA terrorists and wondering what the hell to do with his useless tanks.

I finished my story and looked up at Jill, who was staring hard at me. My army experience had exposed me to some brutal interrogation techniques, but Jill Salton could give my instructors points. ‘So that was it,’ I said. ‘I quit.’

‘But your wife had died earlier.’

‘I was stationed in Germany and my wife was flying out to meet me. The plane crashed.’

She said thoughtfully, ‘You must have married your second wife after you left the army.’

‘I did,’ I said. ‘But how did you figure that?’

‘Any woman who can’t stand the pace of living with a man who works for an insurance company would never be an army wife.’ She put dishes into the oven and closed the door. ‘Dinner in thirty minutes. Time for another drink.’ She came over and picked up my glass. ‘For you?’

‘Thanks.’

As she mixed another shakerful of martinis, she said, ‘What was it like when your wife died?’

‘Bloody,’ I said. ‘It gave me a hell of a knock.’

‘I know.’ She was suddenly still and when she finally turned her head towards me her eyes were bright with unshed tears. ‘I’m glad you’re here, Bill. You understand.’ She slammed down the shaker and said passionately, ‘This damned house!’

The tears came, flowing freely, and I knew what the matter was. Plain loneliness. The reserve that stopped her communicating her inner feelings to her friends melted with a stranger. She was open with me because I would be gone within days and she would probably never see me again, never have to look into my eyes and know that I knew. People who travel receive a lot of confidences from total strangers who would never dream of relating the same stories to their friends.

But there was something else. As she said, I understood: I had been there too, and this made a common bond.

So she cried on my shoulder – literally. I held her in my arms and felt her body tense as she wept. I said the usual incoherent things one says on such an occasion, keeping my voice low and gentle, until the storm blew itself out and she looked up at me and said brokenly, ‘I’m … I’m sorry, Bill. It just … happened suddenly.’

‘I know,’ I said.

I saw her become aware of where she was and what she was doing. Her arms, which had been about me, went limp and to save her embarrassment I released her. She stepped back a pace and touched her tear-stained face. ‘I must look awful.’

I shook my head. ‘Jill, you’re beautiful.’

She summoned a smile from somewhere. ‘I’ll go and clean up and then we’ll have dinner. Don’t expect too much: I’m a terrible cook.’

She was right. She was the only woman I knew who could ruin a frozen meal. But it was another thing that made her more human.

II

We drove into San Martin in my car, the headlights boring holes through the quick-fallen tropical night. She sat relaxed in the passenger seat and we talked casually about anything and everything that didn’t concern her or her husband. She had come back after repairing the damage and we’d had another drink before dinner and neither of us referred to what had happened.

I turned a corner and nearly rammed a large vehicle approaching on the wrong side of the road. It was only strong wrists and quick action that saved us from a collision. The car scraped through a narrow gap which I thought would be impossible and then we were on the other side and safe.