По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

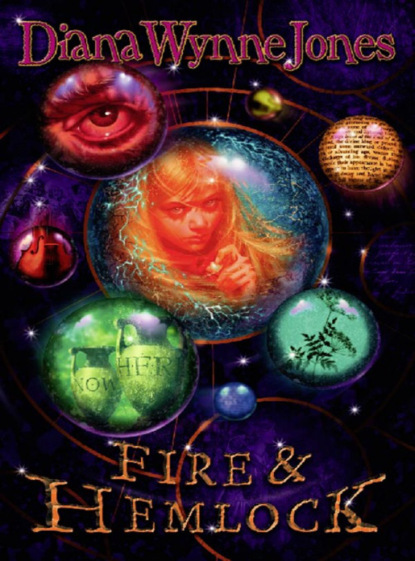

Fire and Hemlock

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Mr Lynn was hurrying down the dingy stairs. “Sorry to trouble you, Carla,” he said. “Hello, Polly – Hero, I should say.”

“Not at all,” said Carla. “I was just going out.” She jerked a pushchair from behind the front door and bumped away with it down the steps, leaving Polly, just for a moment, not at all sure what to say next.

The trouble was, she had been thinking of Mr Lynn as a tortoise-man, or as a sort of ostrich in gold-rimmed glasses, the way he had described himself in his letter – anyway, as rather pathetic and ridiculous – and it was quite a shock to find he was a perfectly reasonable person after all, simply very tall and thin. And it was a further trouble to realise that Mr Lynn did not quite know what to say either. They stood and goggled at one another.

Mr Lynn was wearing jeans and an old sweater. That was partly what made the difference. “You look nicer like that – not in funeral clothes,” Polly said awkwardly.

“I was going to say the same about your dress,” Mr Lynn said in his polite way. “Did you have a good journey?”

“Yes really,” Polly said. She was just going on to say that she had been afraid of Mr Leroy or Laurel following her, when it came to her that she had better not. She was quite sure she should not mention them. Why she was sure, she did not know, but sure she was. She chewed her tongue and wondered what to say instead. It was as awkward as the first day at a new school.

But it was just like that first day. It seems to go on forever, and it is full of strangeness, and the next day you seem to have been there always. The thing Polly thought to say was, “Is Carla your landlady?” Mr Lynn said she was. “But she’s nothing like Edna!” Polly exclaimed.

“No, but Edna lives in Stow-Whatsis,” Mr Lynn said. Then it was all right. They climbed the stairs, both telling one another at once how awful Edna was, and in what ways, and went into Mr Lynn’s flat still telling one another.

Polly thought Mr Lynn’s flat was the most utterly comfortable place she had ever been in. It had nothing grand about it, like Hunsdon House, nor was it pretty, like home. Things lay about in it, but not in the uncared-for way they did in Nina’s house, and it was not nearly as clean as Granny’s. In fact, the bathroom was distinctly the way Polly always got into trouble for leaving bathrooms in. She went over it all. There were really only three rooms. Mr Lynn had a wall full of books, and stacks and wads of printed music, a music stand that collapsed in Polly’s fingers, and an old, battered piano. There were two great black cases that looked as battered as the piano, but when Polly opened them she found a cello nestling inside each, brown and shiny as a conker in its shell, and obviously even more precious than conkers. Polly was delighted to recognise the Chinese horse picture on the wall, and the swirly orchestra picture over the fireplace. The other pictures were leaning by the wall. Mr Lynn said he had not decided where to hang them yet. Polly saw why. There were posters and prints and unframed drawings tacked to the walls all over.

“It’s a very ordinary flat,” Mr Lynn said, “and the real drawback is that it’s not terribly soundproof. Luckily the other tenants seem to like music.” But he sounded pleased that Polly liked the flat so much. He asked her if she liked music. “One of the things we never got round to discussing,” he explained in that polite way of his. Polly said she was not sure she knew music. So he put on a record he thought she might like, and she thought she did like music. Then he let Polly put on records and tapes for herself in a way Dad would never let her do at home. They had it playing all the time. Meanwhile, Polly toasted buns at the gas fire, and Mr Lynn spread them with far too much butter and honey, which Polly had to be careful not to drip on her nice dress while she ate them.

She ate a great deal. The music played, and they went on discussing Edna. Before long they knew exactly the pinched shape of her face and the sound of her nasty, yapping voice. Polly said that the stuffing was coming out of Edna’s dressing gown because she was too mean to buy another, and she only let poor Mr Piper have just enough money each month to buy tobacco. “He had to give up smoking to buy books,” she said.

“I feel for him,” said Mr Lynn. “I had to do that to buy my good cello. What is Edna saving her money for?”

“To give to Leslie,” said Polly.

“Oh, the awful Leslie,” said Mr Lynn. “From what you said in your letter, I see him as dark, sulky, and rather thick-set. Utterly spoiled, of course. Is Edna saving to buy him a motor bike?”

“When he’s old enough. She gives him anything he wants,” said Polly. “She’s just bought him an earring shaped like a skull with diamonds for eyes.”

“Shaped like a skull,” agreed Mr Lynn, “for which he is not in the least grateful. How does he get on with my new assistant?”

“We hate one another,” said Polly. “But I have to be polite to Leslie in case he guesses I’m not a boy.”

“And for fear of annoying Edna,” said Mr Lynn. “She’d have you out like a shot if Leslie told tales.”

When they had settled about Leslie and described the shop to one another – which took a long time, because both of them kept thinking of new things – they went on to Tan Coul himself.

“I don’t understand about him,” Mr Lynn said dubiously. “What relation does he bear to me? I mean, what happens when he’s needed? Do I have to become Mr Piper in order to become Tan Coul, or can I switch straight to Tan Coul from here?”

Polly frowned. “It isn’t like that. You mustn’t ask it to bits.”

“Yes I must,” Mr Lynn said politely. “Please don’t put me off. This is the most important piece of hero business yet, and I think we should get it right. Now – can I switch straight to Tan Coul or not?”

“Ye-es,” Polly said. “I think so. But it’s not that simple. Mr Piper is you too.”

“But I don’t have to rush to Whatsis-on-the-Water and begin each job from there, do I?”

“No. And neither do I,” said Polly.

“That’s a relief,” said Mr Lynn. “Even so, think how awkward it will be if the call comes while I’m in the middle of a concert or you’re doing an exam. How do the calls come, by the way?”

Polly began to feel a bit put-upon. “Things just happen that need us,” she said. “I think. Like the giant. You hear crashing and you run there.”

“With my axe,” Mr Lynn agreed. “Where do you suggest I keep my axe in London?”

Polly turned round, laughing. It was so obvious she hardly needed to point.

“In a cello case, like a gangster?” Mr Lynn said dubiously. “Well, I could get them to make a little satin cushion for it, I suppose.”

Polly looked at him suspiciously. “You’re laughing at me.”

“Absolutely not!” Mr Lynn seemed shocked. “How could I? But I don’t think you realise just how much that good cello cost.”

It was odd, Polly thought then, and later, and nine years after that, remembering it all. She never could completely tell how seriously Mr Lynn took the hero business. Sometimes, like then, he seemed to be laughing at them both. At other times, like immediately after that, he was far more serious about it than Polly was.

“But I still don’t understand about Tan Coul,” he said thoughtfully, with his big hands clasped round his knees – they were sitting at opposite end of the hearth rug. “Where is he when he – or I – do his deeds? Are the giants and dragons and so forth here and now, or are they somewhere else entirely?”

If it had been Nina asking this, Polly would have answered that was not the way you played. But Mr Lynn had already proved that you could not put him off like that, and she could see he was serious. She pushed aside the empty plates and knelt up in order to think strenuously. Her hair got in the way and she hooked it behind her ears.

“Sort of both,” she said. “The other place they come from and where you do your deeds is here – but it’s not here too. It’s—Oh, bother you! I just can’t explain!”

“Don’t get cross,” Mr Lynn begged her. “Maybe there are no words for it.”

But there were, Polly realised. She saw in her mind two stone vases spinning, one slowly, the other fast, and stopping to show half a word each. With them she also saw Seb watching, looking scornful. “Yes there are,” she contradicted Mr Lynn. “It’s like those vases. Now-here and Nowhere.” The idea of Seb was so strong in her mind as she said it that she felt as if she had also told Mr Lynn how Seb had tried to make her promise not to see him.

“Nowhere,” repeated Mr Lynn. “Now-here. Yes, I see.” He was not thinking of Seb at all. Polly did not know whether she was relieved or annoyed. Then he said, “You mentioned a horse in your letter. A Nowhere horse, I suppose. What is my horse like? Do you have one too?”

“No,” said Polly. She would have liked one, but she was sure she had not. “Your Nowhere horse is like that,” she said, pointing to the picture of the Chinese horse on the wall.

They both looked up at it. “I’d hoped for something a bit calmer,” Mr Lynn confessed. “That one obviously kicks and bites. Polly, I don’t think I’d stay on his back five seconds.”

“You’ll have to try,” Polly said severely.

Mr Lynn took it meekly. “Oh well,” he said. “Perhaps if I spoke to it in Chinese—Now, how did I come to find this vicious beast?” They were thinking of various ways Mr Piper could have met the horse, when Mr Lynn happened to see his watch. “When does your mother want you back? Is she coming here?”

“Half past five,” said Polly, and then had an awful moment when she seemed to have forgotten the lawyer’s address. She had just not listened in the taxi. But, because Ivy had made her say it, it had gone down into her memory somehow. She found she could recite it after all.

Mr Lynn unfolded himself and stood up. “Lucky that’s quite near here. Come on. We’d better get going if we’re to be there by five-thirty.”

Polly got her coat. Mr Lynn put on a once shiny anorak almost as worn-out as Edna’s dressing gown, and they set off, down the hollow stairs and into the now dark street. Strangely enough, Polly forgot to look in case Mr Leroy or Laurel were following her. The road was so busy and Londonish and full of traffic that she only thought how glad she was to be able to grab hold of Mr Lynn’s hand, and how grateful she was that he took her a shortcut down small streets where there were fewer cars and even some trees. The trees still had some shivering leaves clinging to them. Polly was just thinking that those leaves looked almost golden in the orange of the streetlights when the noise began in the street round the corner.

It was about seven different noises at once. A car hooter blared. With it were mixed the awful screech of brakes and a splintering, crashing sound. Behind this were angry voices yelling and several screams. But the noises in front of these, which made it obviously different from a simple car crash, were iron-battering sounds and a terrible shrill yelling that was the most panic-stricken noise Polly had ever heard.

Mr Lynn and Polly looked at one another.

“Do you think we should go and see?” Mr Lynn said.

“Yes,” said Polly. “It might be a job for us.” She did not believe it was for an instant, and she knew Mr Lynn did not either, but it seemed the right thing to say.