По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

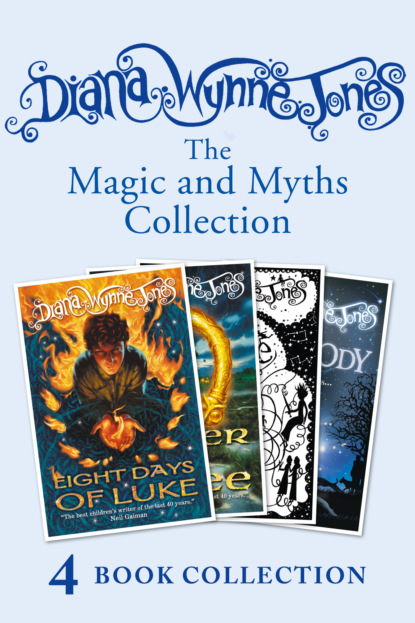

Diana Wynne Jones’s Magic and Myths Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sure enough, if she peered forward and down through the veils of her own hair, she could see the Solar System looking just like it did on Grandpa’s computer. There was the sun in the middle and all the planets sedately circling it. She saw big Neptune and heavy, white Uranus, ringed Saturn and Jupiter looking sultry and yellow, with red blotches on it. Pluto was lurking somewhere out in the dark, while little Mercury and cloudy Venus seemed much too near the sun and likely to fry in its heat. And there circled red Mars and blue Earth.

Hayley began to hope she was aimed properly at Earth, but as she hurtled onwards, it began to look much more as if she was heading straight for the sun. Comets did sometimes plunge into the sun, she knew. Grandpa had told her. She tried to sidle herself more into a line for Earth, but she couldn’t. The sun was actually pulling her.

“Oh, help!” she said. “I’m going to die. What a waste, now I’ve discovered I can do this!”

Then, before she had totally panicked, it seemed as if she was only going to pass very near the sun – to slide by perhaps a mere million miles away. She could already feel the blazing heat from it. When she looked at it, she could clearly see the twirling sunspots and the hissing, leaping lumps of flame. And she could see the person in green clothes standing in the hard, hot midst of it.

“What?” Hayley thought. “People can’t—”

She was still only halfway through that thought, when the person in the sun waved at her and shouted. “Stop!” he yelled. “Match velocities now!”

Hayley found herself – not exactly slowing – gliding beside the sun at about the same speed and much too near for comfort. The heat of it uncurled her, melting her from around her apple. “Don’t do that!” she shouted. And found herself looking across at Flute. “Oh, of course,” she said. “Fiddle said you stood in the sun.”

Flute stood with his arms folded, surrounded in leaping hissing heat. He did not look entirely friendly. “Until this morning,” he said, “I had a thousand and one golden apples. Now I’ve only got a thousand.”

“Are they yours?” Hayley said. “I didn’t know—”

Flute nodded, his hair leaping among the white hot flames. “And you’ve got another one in your pocket,” he said.

Up until then, Hayley had clean forgotten that she had zipped Harmony’s prize apple into one of her trouser pockets. She would have liked to pat that pocket to make sure the plastic apple there was still safe, but she was a little too icy and curled up to do that. She said airily, “Oh, that’s only a plastic apple Harmony gave me for a prize in the game.”

Flute grinned a little. “Is it? That girl Harmony has stolen more of my apples than I care to think of. She now has the run of the universe, probably the whole multiverse. She’s everywhere, in spite of your uncle Jolyon’s orders. Don’t go giving her that new one.”

“I won’t then,” Hayley said. “I want to keep it.”

Flute lost his grin. “Do you? Then you realise you’ll have to pay me for it, don’t you? My apples are never free.”

“Oh,” said Hayley. It was a relief, in a way, to know that she need not be a thief. She hated the idea that she had been stealing from Flute of all people. But it had never occurred to Grandma to give Hayley any money before sending her away. Glumly, knowing she was penniless, Hayley asked, “How much do you want for it?”

“I’ll take,” said Flute, “one of the stars from Orion’s bow. We want that quite urgently, as it happens.”

“Er—” Hayley began.

“I know you haven’t got it now,” said Flute. “You can give it me when you next see me. And I want your promise that you will.”

“I promise,” Hayley said, feeling small and sad. She thought, I’ll have to ask Harmony what I do about that. Oh, dear.

“Very well,” said Flute. “Off you go then.”

Hayley peered through the cloudy spout of her hair and tried to turn herself towards Earth, which had moved quite a way further in its orbit while they talked. She would never have managed it, if Flute had not reached out and given her a shove. This sent her gliding off on a course that would meet Earth as it went on round.

“See you soon,” he called as Hayley headed away.

She was still moving quite fast, but to her disappointment not hurtling along any more. She was simply travelling on her own inertia and getting cooler again as she moved. She went from hot, to warm, to balmy, to lukewarm and, in spite of this, she melted steadily. Even when she glided into truly cold air somewhere on the night side of Earth, she was still melting. Dripping and distressed, she came uncurled in darkness and her hair fell back again around her shoulders as she landed and knew she was a human girl again. It was a dreadful loss. Hayley could not help sobbing a little as she stood still and carefully stowed the golden apple in another pocket with a zip. She sniffed and wondered which way to go.

Someone came up to her in the near dark and said, “You need to take this strand here.”

Hayley peered. She could see the strand, if she strained, like a path made of coal. “It doesn’t look very inviting,” she said.

“Well, you are on the dark side here,” the man said.

Hayley was sure she recognised his voice. She turned and peered up at his face. Under a black cap, his hair seemed white, and it blew about rather. “You’re Fiddle!” she said. “I’ve just met your brother again. And,” she added miserably, “I’m not a comet any more.”

“I know,” Fiddle said. “You can always be one again later.”

Hayley’s eyes seemed to have got keener for her time as a comet. She could pick out Fiddle’s face quite clearly now. Although it was a sad face, it really was remarkably like Flute’s. “Are you and Flute twins, by any chance?” she asked him.

“That’s right,” he said. “We take it in turns to stand in the sun.”

CHAPTER NINE (#u96a28334-2f6d-550c-823d-2c51b8ac69e8)

Fiddle came a little way along the coaly path with Hayley. He said he wanted to make sure she didn’t miss the way, but Hayley was fairly sure he was being kinder than that. There seemed to be horrible things going on on either side of the path. There were screams and groans, and somewhere someone who sounded to be dying kept saying, “Water! Water! Oh, please, water!” Fiddle hurried Hayley along and Hayley tried not to look, until they came to a place where the air was full of desperate panting and a sort of grinding sound. Hayley could not help looking here.

There was a hill to one side and she could dimly see someone trying to heave a boulder up it. All she could really see was a pair of straining legs in ragged trousers, some way above her head. But just as she looked, the person lost control of the boulder and it came rolling and crashing down, bringing the man with it. “Oh, curses!” he cried out, ending up in a heap, half under the boulder, almost at Hayley’s feet.

“Is he all right?” Hayley said to Fiddle. She thought the man might be crying.

Fiddle pushed her on. “Not really,” he said. “But there are no bones broken. He has to get up and push the stone again until he gets it to the top of the hill.”

“Why?” said Hayley.

“Because your uncle Jolyon says so,” Fiddle said. “He’s in charge here. This is what happens to people who offend him.”

Hayley was glad to think she had never liked Uncle Jolyon. “Can’t anyone stop him?” she said.

“Not very easily,” Fiddle said, “though they tell me that a seer called the Pythoness said it could be done. We’re trying to find a way. Now this is where I have to leave you. You’ll find things become more and more normal from here on, but do try to keep going whatever you see.”

“Will I see you again?” Hayley said.

“Quite probably,” Fiddle answered. He waved to her and turned back up the path.

Hayley sadly watched him go. Even though she had only talked to him once and nodded to him with Martya, she always thought of Fiddle as her first real friend. She sighed and walked on.

The path became a passage with barred prison cells on either side of it. Behind one of the thick doors, someone was yelling out, “I hate the lot of you! The whole lot of you!” From behind other doors, chains clinked.

I suppose this is more normal, Hayley thought, shivering.

She marched on. The passage went from arched stone to dingy brick and then to modern-looking concrete with strip lights in the ceiling, but there were still prison cells on either side. She came to a squarer part, where soldiers with guns were kicking someone who was writhing about on the floor. This was more normal, Hayley supposed. There had been scenes like this on Grandpa’s telly. But seen up close it was very nasty.

“You ought to be ashamed of yourselves!” she told the soldiers.

Only one of them took any notice. He swivelled his gun round to point at Hayley. “Get out!” he said to her. And the woman soldier who seemed to be in charge snapped, “Shoot her,” without looking up from kicking.

Hayley moved on in a hurry. There seemed to be nothing else she could do. Next moment, she was in a huge office, very brightly lighted, where people sat at desks in rows, all hard at work with computers and telephones. Hayley pattered quickly down the space at the side of the desks, hoping not to be noticed, until she came to the desk at the very end, where there was a man who seemed to be working harder than all the others put together.

Here something made Hayley stop and look. This man had a large tray marked IN on one side of his desk, piled with papers, forms and plastic files. He was snatching these out at the rate of two a minute, studying them swiftly, marking some with a pen, putting some in a copier and then snatching them out, making notes about them on his computer, signing both copies and slapping them into a smaller tray marked OUT. Then he snatched up another set. He was going so quickly that Hayley was sure that he was going to get the IN-tray empty any second. But, just as he was down to one file and two forms, someone came along and dumped another huge pile on top of them. The man groaned and started working on those.

What had made Hayley stop and stare, however, was not how hard the man was working: it was the look of him. He had black curly hair and a brownish skin. The curly hair was receding from his wrinkled forehead and there were rays of further wrinkles fanning from the sides of his big black eyes. He looked familiar. The way he moved was a way Hayley knew. In fact, although he was not young, he looked extraordinarily like the young man in the wedding photo that Grandma kept on Hayley’s mantelpiece.