По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

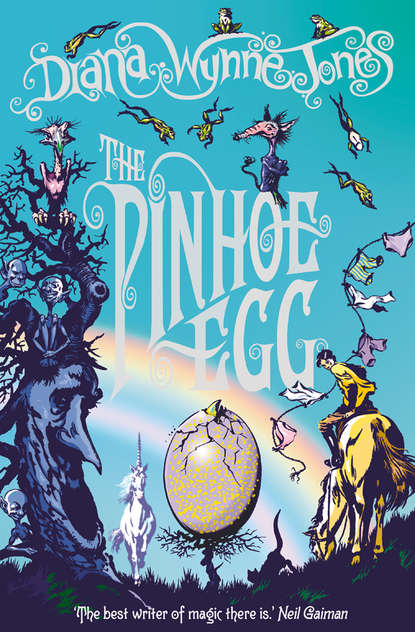

The Pinhoe Egg

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Rats!” said Joe, hunching himself.

Chrestomanci watched Joe slouch out of the room. “What an eccentric youth,” he remarked when the door had finally shut. He turned to Cat, looking much less pleasant. “Cat —”

“I know,” Cat said. “But he didn’t believe —”

“Have you read the story of Puss in Boots?” Chrestomanci asked him.

“Yes,” Cat said, puzzled.

“Then you’ll remember that the ogre was killed by being tempted to turn into something very large and then something small enough to be eaten,” Chrestomanci said. “Be warned, Cat.”

“But —” said Cat.

“What I’m trying to tell you,” Chrestomanci went on, “is that even the strongest enchanter can be defeated by using his own strength against him. I’m not saying this lad was —”

“He wasn’t,” said Cat. “He was just curious. He uses magic himself and I think he thinks it goes by size, how strong you are.”

“A magic user. Is he now?” Chrestomanci said. “I must find out more about him. Come with me now for an extra magic theory lesson as a penalty for using magic indoors.”

But Joe was all right really, Cat thought mutinously as he limped down the spiral stairs after Chrestomanci. Joe had not been trying to tempt him, he knew that. He found he could hardly concentrate on the lesson. It was all about the kind of enchanter’s magic called Performative Speech. That was easy enough to understand. It meant that you said something in such a way that it happened as you said it. Cat could do that, just about. But the reason why it happened was beyond him, in spite of Chrestomanci’s explanations.

He was quite glad to see Joe the next morning on his way out to the stables. Joe dodged out of the boot room into Cat’s path, in his shirtsleeves, with a boot clutched to his front. “Did you get into much trouble yesterday?” he asked anxiously.

“Not too bad,” Cat said. “Just an extra lesson.”

“That’s good,” said Joe. “I didn’t mean to get you caught – really. The Big Man’s pretty scary, isn’t he? You look at him and you sort of drain away, wondering what’s the worst he can do.”

“I don’t know the worst he can do,” Cat said, “but I think it could be pretty awful. See you.”

He went on out into the stableyard, where he could tell that Syracuse knew he was coming and getting impatient to see him. That was a good feeling. But Joss Callow insisted that there were other duties that came first, such as mucking out. For someone with Cat’s gifts, this was no trouble at all. He simply asked everything on the floor of the loose box to transfer itself to the muck heap. Then he asked new straw to arrive, watched enviously by the stableboy.

“I’ll do it for the whole stables if you like,” Cat offered.

The stableboy regretfully shook his head. “Mr Callow’d kill me. He’s a great believer in work and elbow grease and such, is Mr Callow.”

Cat found this was true. Looking after Syracuse himself, Joss Callow said, could never be done by magic. And Joss was in the right of it. Syracuse reacted very badly to the merest hint of magic. Cat had to do everything in the normal, time-consuming way and learn how to do it as he went.

The other part of the problem with Syracuse was boredom. When Cat, now wearing what had been Janet’s riding gear most artfully adapted by Millie, had got Syracuse tacked up ready to ride, Joss Callow decreed that they went into the paddock for a whole set of tame little exercises. Cat did not mind too much, because his aches from yesterday came back almost at once. Syracuse objected mightily.

“He wants to gallop,” Cat said.

“Well he can’t,” said Joss. “Or not yet. Lord knows what that wizard was up to with him, but he needs as much training as you do.”

When he thought about it, Cat was as anxious to gallop across open country as Syracuse was. He told Syracuse, Behave now and we can do that soon. Soon? Syracuse asked. Soon, soon? Yes, Cat told him. Soon. Be bored now so that we can go out soon. Syracuse, to Cat’s relief, believed him.

Cat went away afterwards and considered. Since Syracuse hated magic so much, he was going to have to use the magic on himself instead. He was forbidden to use magic in the Castle, so he would have to use it where it didn’t show. He used it, very quietly, to train and tame all the new muscles he seemed to need. He let Syracuse show him what was needed, and then he used the strange unmagical magic that there seemed to be between himself and Syracuse to show Syracuse how to be patient in spite of being bored. It went slower than Cat hoped. It took longer than it took Janet, laughing hilariously, to teach Julia to ride her new bicycle. Roger, Julia and Janet were all pedalling joyfully around the Castle grounds and down through the village long before Cat and Syracuse were able to satisfy Joss Callow.

But they did it quite soon. Sooner than Cat had believed possible, really, Joss allowed that they were now ready to go out for a real ride.

They set off, Joss on the big brown hack beside Cat on Syracuse. Syracuse was highly excited and inclined to dance. Cat prudently stuck himself to the saddle by magic, just in case, and Joss kept a stern hand on Cat’s reins while they went up the main road and then up the steep track that led to Home Wood. Once they were on a ride between the trees, Joss let Cat take Syracuse for himself. Syracuse whirled off like a mad horse.

For two furlongs or so, until Syracuse calmed down, everything was a hard-working muddle to Cat, thudding hooves, loud horse breath, leaf mould kicked up to prick Cat on his face, and ferns, grass and trees surging past the corners of his eyes, ears and mane in front of him. Then, finally, Syracuse consented to slow to a mere trot and Joss caught up. Cat had space to look around and to smell and see what a wood was like when it was in high summer, just passing towards autumn.

Cat had not been in many woods in his life. He had lived first in a town and then at the Castle. But, like most people, he had had a very clear idea of what a wood was like – tangled and dark and mysterious.

Home Wood was not like this at all. Any bushes seemed to have been tidied away, leaving nothing but tall dark-leaved trees, ferns and a few burly holly trees, with long straight paths in between. It smelt fresh and sweet and leafy. But the new kind of magic Cat had been learning through Syracuse told him that there should have been more to a wood than this. And there was no more. Even though he could see far off through the trees, there was no depth to the place. It only seemed to touch the front of his mind, like cardboard scenery.

He wondered, as they rode along, if his idea of a wood had been wrong after all. Then Syracuse surged suddenly sideways and stopped. Syracuse was always liable to do this. This was one reason why Cat stuck himself to the saddle by magic. He did not fall off – though it was a close thing – and when he had struggled upright again, he looked to see what had startled Syracuse this time.

It was the fluttering feathers of a dead magpie. The magpie had been nailed to a wooden framework standing beside the ride. Or maybe Syracuse had disliked the draggled wings of the dead crow nailed beside the magpie. Or perhaps it was the whole framework. Now that Cat looked, he saw dead creatures nailed all over the thing, stiff and withering and beyond even the stage when flies were interested in them. There were the twisted bodies of moles, stoats, weasels, toads, and a couple of long blackened tube-like things that might have been adders.

Cat shuddered. As Joss rode up, he turned and asked him, “What’s this for?”

“Oh, it’s nothing,” Joss said. “It’s just – Oh, good morning, Mr Farleigh.”

Cat looked back in the direction of the grisly framework. An elderly man with ferocious side whiskers was now standing beside it, holding a long gun that pointed downwards from his right elbow towards his thick leather gaiters.

“It’s my gibbet, this is,” the man said, staring unlovingly up at Cat. “It’s for a lesson. And an example. See?”

Cat could think of nothing to say. The long gun was truly alarming.

Mr Farleigh looked over at Joss. He had pale, cruel eyes, overshadowed by mighty tufts of eyebrow. “What do you mean bringing one like him in my wood?” he demanded.

“He lives in the Castle,” Joss said. “He’s entitled.”

“Not off the rides,” Mr Farleigh said. “Make sure he stays on the cleared rides. I’m not having him disturbing my game.” He pointed another pale-eyed look at Cat and then swung around and trudged away among the trees, crushing leaves, grass and twigs noisily with his heavy boots.

“Gamekeeper,” Joss explained. “Walk on.”

Feeling rather shaken, Cat induced Syracuse to move on down the ride.

Three paces on, Syracuse was walking through the missing depths that the wood should have had. It was very odd. There was no foreground, no smooth green bridle path, no big trees. Instead, everywhere was deep blue-green distance full of earthy, leafy smells – almost overpoweringly full of them. And although Cat and Syracuse were walking through distance with no foreground, Cat was fairly sure that Joss, riding beside them, was still riding on the bridle path, through foreground.

Oh, please, said someone. Please let us out!

Cat looked up and around to find who was speaking and saw no one. But Syracuse was flicking his ears as if he too had heard the voice. “Where are you?” he asked.

Shut behind, said the voice – or maybe it was several voices. Far inside. We’ve been good. We still don’t know what we did wrong. Please let us out now. It’s been so long.

Cat looked and looked, trying to focus his witch sight as Chrestomanci had taught him. After a while, he thought some of the blue distance was moving, shifting cloudily about, but that was all he could see. He could feel, though. He felt misery from the cloudiness, and longing. There was such unhappiness that his eyes pricked and his throat ached.

“What’s keeping you in?” he said.

That – sort of thing, said the voices.

Cat looked where his attention was directed and there, like a hard black portcullis, right in front of him, was the framework with the dead creatures nailed to it. It seemed enormous from this side. “I’ll try,” he said.

It took all his magic to move it. He had to shove so hard that he felt Syracuse drifting sideways beneath him. But at last he managed to swing it aside a little, like a rusty gate. Then he was able to ride Syracuse out round the splintery edge of it and on to the bridle path again.