По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

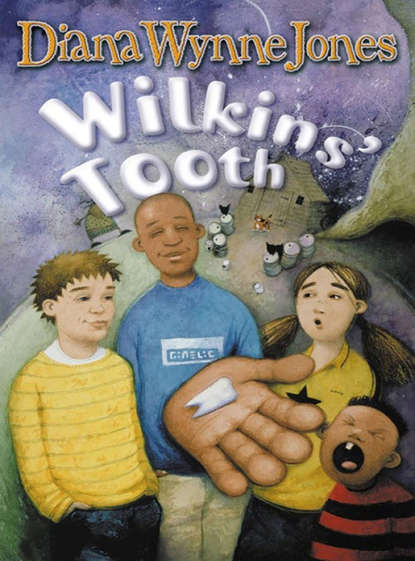

Wilkins’ Tooth

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Though it shouldn’t be, really,” she said, “because we’re not a proper company.”

“Yes,” said Frank, “but if anyone asks us something too difficult, we can always say it means Limited Own Back, and we don’t touch things too big for us.”

The next morning, they pinned the notice to the back of the potting shed, where it could be seen by anyone who went along the path beside the allotments, and sat in the shed with the back window open to wait for orders.

All that happened, that entire day, was that two ladies exercising their dogs saw it and shrieked with laughter.

“Oh look, Edith! How sweet!”

“Limited too! The idea!”

Frank and Jess could hear them laughing about it all down the path.

“Take no notice,” said Jess. “Just think of when the shekels start to pour in.”

That was all very well, but Frank began to wonder if they were going to spend the entire Easter holiday sitting in the potting shed being laughed at. It was a dismal place at the best of times, and the view over the allotments always depressed him. They were dank and low. Beyond them, there was the marshy, tangled waste strip beside the river where everyone threw rubbish, and, under the trees, the hut-thing where old Biddy Iremonger lived. The only real house in sight was as damp-looking and dreary as the rest – a big square place, the colour of old cheese. The trees had been slow to put out leaves that year, so it was all as blank and bleak as winter.

The next day was, if anything, worse still. To start with, it was raining on and off, with a cold wind steadily blowing showers up and away again. Draughts whined through the potting shed and fluttered all the cobwebs. Jess and Frank sat in their coats and began to think their idea was a failure.

“And we can’t even buy sweets to console ourselves with,” Jess was saying, when somebody rapped on the window.

They looked up to see old Mr Carter, who had the nearest allotment, leaning on the sill of the potting shed window.

“This your notice?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Frank, feeling foolish and rather defiant about it. “Why?”

Mr Carter bent down and read the notice, out loud, so that Frank felt even more foolish by the time he finished, and Jess went very pink. “My, my!” said Mr Carter. “Just wait till the Prime Minister hears of this. He’ll have you in his Cabinet. Got any customers yet?”

“Not yet,” Frank admitted.

“We’ve not been in business long,” Jess said.

“Well,” said Mr Carter, “I can’t help with the revenge part, but I know where you’ll find some treasure.”

“Do you? Where?” they said. Jess reached for her notebook to take down the details.

“Yes,” said Mr Carter. “Rainbow, this morning. Ended right beside Biddy Iremonger’s place. Saw it with my own eyes. You dig there, and there’ll be a crock of gold for you.” And, before either of them could answer, he went away laughing.

“Beast!” said Jess.

Frank was too angry even to say what he thought. Instead, he suggested taking the notice down. Jess said that would be giving in too easily.

“Let’s keep it the rest of today and tomorrow,” she said. “Maybe the news will get round.”

“Then we’ll have the whole town knocking on the window to laugh at us,” said Frank, and he went indoors to cadge some biscuits to cheer them up with.

They were eating the biscuits when they heard quite a crowd of people coming along the path. There was a noise of wheels turning and sticks being trailed along the allotment railings and the fences of the gardens. There were also loud, crude voices, swearing. Frank wished most heartily that Jess had agreed to take the notice down. He did not even need to hear the voices to know that it was Buster Knell and his gang – and, to judge from the language, Buster Knell and his gang in a very bad mood indeed. They all stopped outside the potting shed, and Jess said afterwards that she saw the air turn blue.

“Cor! Take a blanking look at this!” said someone. “Look, Buster.”

“Blanketty Own Back!” said someone else.

Frank and Jess sat and looked at one another, while yet another boy read the notice out in a jeering squeaky voice. “Whose blanking idea is this?” he said.

“Blankery-blue Pirie kids,” they heard Buster say. They knew it was Buster, because his voice was louder and his language nastier than any of the others’. “Always got some blank idea or other.”

“Fwank and Jessie,” squeaked someone. “Come on, let’s tear it down.”

The whole gang agreed, at the tops of their voices and the full width of their language. Frank and Jess had resigned themselves to losing their notice, when Buster shouted:

“No! I got a much better blanking blue-and-purple idea than that. Wait a blanketty minute, can’t you!” Then, before Frank and Jess had time to escape from the shed, he was pounding on the window, yelling, “Anyone in? You too blanking scared to answer? Open purple up, can’t you!”

There was nothing else for it. Frank got up and opened the window. Buster put his arms on the sill and pushed his face inside. It was not a nice face at the best of times – all thick and narrow-eyed. At that moment, it was mud down one side, and thicker than usual down the other. There was even blood, just a little, on Buster’s stumpy chin.

“What do you want?” asked Frank.

“My crimson Own Back,” said Buster. “Like it says. And you blanking-blue owe me ten pence anyway.”

“So?” said Frank, as bravely as he could. Beyond Buster was all the gang, glowering and muddy, carrying sticks and air guns, and towing their usual number of home-made go-carts. They never moved without all this equipment if they could help it, and they knew how to use it too.

Buster stuck his face sneeringly into Frank’s. Jess began gently collecting flowerpots for ammunition. It looked as if they were going to need all they could get.

“I’ll let you off that purple ten pence,” said Buster, “if you can get me my blanking Own Back on that blue-and-orange scum. Only I bet you’re too blanking scared.”

“No, I’m not,” said Frank. “Who do you mean?”

“Crimson scum,” said Buster. “Vernon Wilkins. Just look what he done to me. Here, take a look.” He pushed his hand towards Frank’s face, and held it open, palm upwards. On it was something small, dirty and red at one end. “See that?” said Buster. “That’s a tooth, that is. That crimson scum knocked it out for me. What do you say to that?”

The only thing Frank could think of to say was that it was rather clever of Vernon Wilkins, but he did not dare say that.

Buster pushed his hand further into the shed. “And you,” he said to Jess. “You take a purple look too. A good long, orange look.”

So Jess was forced to come and inspect the tooth too. She brought a flowerpot with her, just in case. It was a double tooth, worn down to a flat disc-shape. “Yes,” she said. “What do you want us to do about it?”

“Get one of his,” said Buster. “You’re arranging crimson revenge, aren’t you? Well, you go and knock me out one of Wilkins’ blue-blanking teeth and bring it back here so I can see you done it. Then I’ll let you off that ten pence.”

“It’s worth more than ten pence,” said Jess.

“Is it?” said Buster. “What’s the orange matter? Do you want to lose a tooth too?”

“Shut up,” said Frank. “When do you want it?”

“It’ll take at least an hour,” said Jess.

“All right,” said Buster. “Meet you back here in an hour. And you’d better bring that green-blue-muddy-violet tooth with you, or it won’t be only ten pence you owe me.” Then he took his hand, and his tooth, and finally his face, away from the window, and led his gang clattering and wheeling and swearing away up the path.

Jess and Frank stared at one another and felt that everything had gone wrong. The idea seemed to have turned back to front. Instead of other people asking them to get their Own Back on Buster Knell, here was Buster Knell sending them for other people’s teeth. The nasty thought was that Vernon Wilkins was a good two years older than Frank, and, if he could actually knock a tooth out of Buster’s head, then there was no knowing what he could do to Frank.