По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

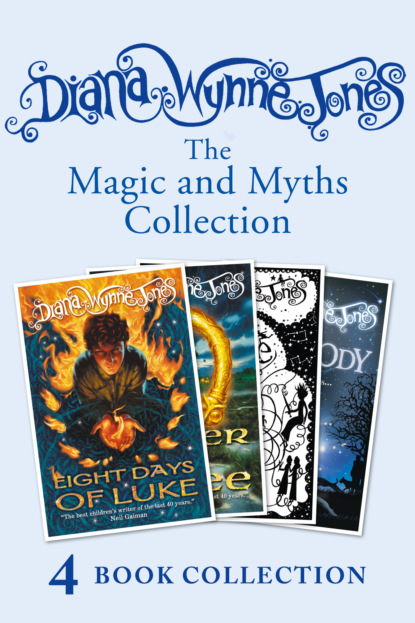

Diana Wynne Jones’s Magic and Myths Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Shut up!” Orban snarled at her. He made a swift left-handed snatch at the collar. “Give me that!”

The Dorig dodged. “I can’t!” it said desperately. “Tell him I can’t,” it said to Adara.

“Orban, you know he can’t,” said Adara. “If it was yours, it could only be taken off your dead body.”

This only made it clear to Orban that he would have to kill the creature. He had gone too far to turn back with dignity, and the knowledge maddened him further. Anyway, what business had the Dorig to imitate the customs of men? “I told you to shut up,” he said to Adara. “Besides, it’s only a stolen collar, and that’s not the same. Give it!” He advanced on the Dorig.

It backed away from him, looking quite desperate. “Be careful! I’ll put a curse on the collar if you try. It won’t do you any good if you do get it.”

Orban’s reply was to snatch at the collar again. The Dorig side-stepped, though only just in time. But it managed, in spite of its shaking fingers, to get the collar round its neck, making it much more difficult for Orban to grab. Then it began to curse. Adara marvelled, and even Orban was daunted, at the power and fluency of that curse. They had no idea Dorig knew words that way.

In a shrill hasty voice, the creature laid it on the collar that the words woven in it should in future work against the owner, that Power should bring pain, Riches loss, Truth disaster, and ill-luck of all kinds follow the feet and cloud the mind of the possessor. Then it ran its pale fingers along the intricate twists and pattern of the design, bringing each part it touched to bear on the curse: fish for loss by water, animals for loss by land, flowers for death of hope, knots for death of friendship, fruit for failure and barrenness, and each, as they were joined in the workmanship, to be joined in the life of the owner. At last, touching the owl’s head at either end, it laid on them to be guardians and cause the collar’s owner to cling to it and keep it as if it were the most precious thing he knew.

When this was said, the Dorig paused. It was panting and palely flushed. “Well? Do you still want it?”

Adara was appalled to hear so much beauty spoilt and such careful workmanship turned against itself. “No!” she said. “And do get them to make you another one when you get home.”

But Orban listened feeling rather cunning. He noticed that not once had the Dorig invoked any higher Power than that of the collar itself. Without the Sun, the Moon or the Earth, even such a curse as this could only bring mild bad luck. The creature must take him for a fool. The Giants began thumping away again beyond the horizon, as if they were applauding Orban’s acuteness. Determined not to be outwitted, Orban flung himself on the Dorig and got his hand hooked round the collar before it could move. “Now give it!”

“No!” The Dorig kept both hands to the collar and pulled away. Orban swung his new sword and brought it down on the creature’s head. It bowed and staggered. Adara flung herself on Orban and tried to pull him away. Orban pushed her over with an easy shove of his right elbow and raised his sword again. Beyond the horizon, the Giants thundered like rocks raining from heaven.

“All right!” cried the Dorig. “I call on the Old Power, the Middle and the New to hold this curse to my collar. May it never loose until the Three are placated.”

Orban was furious at this duplicity. He brought his sword down hard. The Dorig gave a weak cry and crumpled up. Orban wrenched the collar from its neck and stood up, shaking with triumph and disgust. The Giants’ noise stopped, leaving a thick silence.

“Orban, how could you!” said Adara, kneeling on the turf of the old road.

Orban looked contemptuously from her to his victim. He was a little surprised to see that the blood coming out of the pale corpse was bright red and steamed a little in the cold air. But he remembered that fish sometimes come netted with blood quite as red, and that things on a muck-heap steam as they decay. “Get up,” he said to Adara. “The only good Dorig is a dead Dorig. Come on.”

He set off for home, with Adara pattering miserably behind. Her face was pale and stiff, and her teeth were chattering. “Throw the collar away, Orban,” she implored him. “It’s got a dreadful strong curse on it.”

Orban had, in fact, been uneasily wondering whether to get rid of the collar. But Adara’s timidity at once made him obstinate. “Don’t be a fool,” he said. “He didn’t invoke any proper Powers. If you ask me, he made a complete mess of it.”

“But it was a dying curse,” Adara pointed out.

Orban pretended not to hear. He put the collar into the front of his jacket and firmly buttoned it. Then he made a great to-do over cleaning his sword, whistling, and pretending to himself that he felt much better about the Dorig than he did. He told himself he had just acquired a valuable piece of treasure; that the Dorig had certainly told a pack of lies; and that if it had told the truth, he had just struck a real blow at the enemy; and the only good Dorig were dead ones.

“We’d better ask Father about those Powers,” Adara said miserably.

“Oh no we won’t!” said Orban. “Don’t you dare say a word to anyone. If you do, I’ll put the strongest words I know on you. Go on – swear you won’t say a word.”

His ferocity so appalled Adara that she swore by the Sun and the Moon never to tell a living soul. Orban was satisfied. He did not bother to consider why he was so anxious that no one should know about the collar. His mind conveniently sheered off from what Og would say if he knew his son had killed an unarmed and defenceless creature for the sake of a collar which was cursed. No. Once Adara had sworn not to tell, Orban began to feel pleased with the morning’s work.

It was otherwise with Adara. She was wretched. She kept remembering the look of pleasure in the Dorig’s yellow eyes when it saw she was ready to believe it, and their look of despair when it invoked the Powers. She knew it was her fault. If she had not said the words right, Orban would not have killed the Dorig and brought home a curse. She could have gone on thinking the world of Orban instead of knowing he was just a cruel bully.

For Adara, almost the worst part was her disillusionment with Orban. It spread to everyone in Otmound. She looked at them all and listened to them talk, and it seemed to her that they would all have done just the same as Orban. She told herself that when she grew up she would never marry – never – unless she could find someone quite different.

But quite the worst part was not being able to tell anyone. Adara longed to confess. She had never felt so guilty in her life. But she had sworn the strongest oath and she dared not say a word. Whenever she thought of the Dorig she wanted to cry, but her guilt and terror stopped her doing even that. First she dared not cry, then she found she could not. Before a month passed she was pale and ill and could not eat.

They put her to bed, and Og was very concerned. “What’s on your mind, Adara?” he said, stroking her head. “Tell me.”

Adara dared not say a word. It was the first time she had kept a secret from her father and it made her feel worse than ever. She rolled away and covered her head with the blanket. If only I could cry! she thought. But I can’t, because the Dorig’s curse is working.

Og was afraid someone had put a curse on Adara. He was very worried because Adara was far and away his favourite child. He had lamps lit and the right words said, to be on the safe side. Orban was terrified. He thought Adara had told Og about the Dorig. He stormed in on Adara where she lay staring up at the thatch and longing to confess and cry.

“Have you said anything?” Orban demanded.

“No,” Adara said wretchedly.

“Not even to the walls or the hearthstone?” Orban asked suspiciously, since he knew this was how secrets often got out.

“No,” said Adara. “Not to anything.”

“Thank the Powers!” said Orban and, greatly relieved, he went off to put the collar in a safer hiding-place.

Adara sat up as he went. He had put a blessed, splendid idea into her head. She might not be able to tell Og or even the hearthstone, but what was to prevent her confessing to the stones of the old Giants’ road? They had watched it all anyway from under the turf. They had received the Dorig’s blood. She could go and remind them of the whole story, and maybe then she could cry and feel better.

Og was pleased to see how much better Adara was that same evening. She ate a natural supper and slept properly all night. He allowed her to get up the next morning, and the next day he allowed her to go out.

This was what Adara had been waiting for. Outside Otmound she stayed for a while among the sheep, until she was sure no one was anxiously watching her. Then she ran her hardest to the old road.

It was a hot day. The grey mists of the Moor hung heavily and the trees were dark. When Adara, panting and sweating, reached the dip in the track, all she found was a column of midges circling in the air above it. There was not a trace of the Dorig – not so much as a drop of blood on a blade of grass – yet her memory of it was so keen that she could almost see the scaly body lying there.

“He looked so small!” she exclaimed, without meaning to. “And so thin! And he did bleed so!”

Her voice rang in the thick silence. Adara jumped. She looked hurriedly round, afraid that someone might have heard. But nothing moved in the rushes by the track, no birds flew and the distant hedge was silent. Even the Giants made no sound. High above Adara’s head was the little white circle of the full Moon, up in broad daylight. She knew that was a good omen. She went down on her knees in the grass and, looking through to the old stones, began her confession.

“Oh stones,” she said, “I have such a terrible thing to remind you of.” And she told it all, what she had said, what Orban had said, and what the poor frightened Dorig had said, until she came to herself saying, “off your dead body.” Then she cried. She cried and cried, rocking on her knees with her hands to her face, quite unable to stop, buried in the relief of being able to cry at last.

A little mottled grass-snake, which had been coiled all this while in the middle of the nearest clump of rushes, now poured itself down on to the warm turf and waited, bent into an S-shape, beside Adara. When she did nothing but rock and cry, it reared up with its yellow eyes very bright and wet, and uttered a soft Hssst! Adara never heard. She was too buried in sorrow.

The snake hesitated. Then it seemed to shrug. Adara, as she wept, thought she felt a chill and a rising shadow beside her, but she was not aware of anything more until a small voice at her shoulder said imperiously, “Well, go on, can’t you! What did my brother say next?”

Adara’s head whipped round. She found herself face to face with a small Dorig – a very small Dorig, no bigger than she was – who was kneeling beside her on the track. His eyes were browner than the dead Dorig’s, and he had a stouter, fiercer look, but she could see a family likeness between them. This one was obviously much younger. He did not seem to have grown scales yet. His pale body was clothed in a silvery sort of robe and the gold collar on his neck was a plain, simple band, suitable for somebody very young. Adara knew he could not possibly harm her, but she was still horrified to see him.

“Go on!” commanded the small Dorig, and his yellow-brown eyes filled with angry tears. “I want to know what happened next.”

“But I can’t!” Adara protested, also in tears again. “I swore to Orban by the Sun and the Moon not to tell a soul, and if you heard me I’ve broken it. The most dreadful things will happen.”

“No, they won’t,” said the little Dorig impatiently. “You were telling it to the stones, not to me, and I happened to overhear. What’s to stop you telling the stones the rest?”

“I daren’t,” said Adara.

“Don’t be stupid,” said the Dorig. “I’ve been coming here and coming here for nearly a month now, and I’ve got into trouble every time I got home, because I wanted to find out what happened. And now you go and stop at the important part. Look.” His long pale finger pointed first to the ground, then up at the white disc of the Moon, and then moved on to point to the Sun, high in the South. “Three Powers present. You were meant to tell, don’t you see? But if you’re too scared, it doesn’t matter. I know it must have been your brother Orban who killed my brother and stole his collar.”

“Oh, all right then,” Adara said drearily. “Stones, it was my brother. I tried to stop him but he pushed me over.”

“Didn’t my brother say anything else?” prompted the Dorig boy.