По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

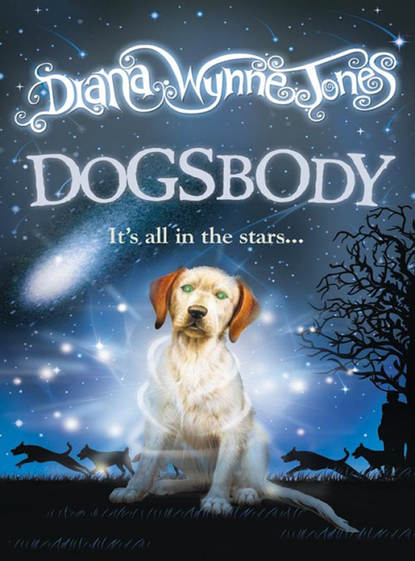

Dogsbody

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But he went on pulling. The indignity was too much. He was not a slave, or a prisoner. He was Sirius. He was a free luminary and a high effulgent. He would not be held. He braced his four legs, and Kathleen had to walk backwards, towing him.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_1cbda400-7a7d-5ecd-a8a6-e88f2ab7320f)

Being towed is hard on the paws, let alone the legs and ears. But Sirius was stiff with shock and Kathleen had to drag him right down the passage. He was not what he seemed. He felt as if the world had stopped, just in front of his forefeet, and he was looking down into infinite cloudy green depths. What was down in those depths frightened him, because he could not understand it.

“Really, Leo!” said Kathleen, at the end of the passage.

Sirius gave in and began to walk, absently at first, trying to understand what had happened. But he had no leisure to think. As soon as they were in the street, half a million new smells hit his nose simultaneously. Kathleen was walking briskly, and so were other legs round her. Beyond, large groaning things shot by with a swish and a queer smell. Sirius pulled away sideways to have a closer look at those things and was distracted at once by a deliciously rotten something in the gutter. When Kathleen dragged him off that, there were smells several dogs had left on a lamp-post and, beyond that, a savoury dustbin, decaying fit to make his mouth water.

“No, Leo,” said Kathleen, dragging.

Sirius was forced to follow her. It irked his pride to be so small and weak when he knew he had once been almost infinitely strong. How had he come to be like this? What had happened to reduce him? But he could not think of the answer when something black was trickling on the pavement, demanding to be sniffed all over at once.

“Leave it,” said Kathleen. “That’s dirty.”

It seemed to Sirius that Kathleen said this to everything really interesting. It seemed to Kathleen that she had said it several hundred times before they came to the meadow by the river. And here more new smells imperiously wanted attention. Kathleen took off the lead and Sirius bounded away, jingling and joyful, into the damp green grass. He ranged to and fro, rooting and sniffing, his tail crooked into a stiff and eager question mark. Beautiful. Goluptious scents. What was he looking for in all this glorious green plain? He was looking for something. He became more and more certain of that. This bush? No. This smelly lump, then? No. What then?

There was a scent, beyond, which was vaguely familiar. Perhaps that was what he was looking for. Sirius galloped questing towards it, with Kathleen in desperate pursuit, and skidded to a stop on the bank of the river. He knew it, this whelming brown thing – he dimly remembered – and the hair on his back stood up slightly. This was not what he was looking for. And surely, although it was brown and never for a second stopped crawling past him, by the smell it was only water? Sirius felt he had better test this theory – and quickly. The rate the stuff was crawling, it would soon have crawled right past and away if he did not catch it at once. He descended cautiously to it. Yes, it was water, crawling water. It tasted a good deal more full-bodied that the water Kathleen put down for him in the kitchen.

“Oh, no!” said Kathleen, panting up to find him black-legged and stinking, lapping at the river as if he had drunk nothing for a week. “Come out.”

Sirius obligingly came out. He was very happy. He wiped some of the mud off his legs on to Kathleen’s and continued his search of the meadow. He still could not think what he was looking for. Then, suddenly, as puppies do, he got exhausted. He was so tired that all he could do was to sit down and stay sitting. Nothing Kathleen said would make him move. So she sat down beside him and waited until he had recovered.

And there, sitting in the centre of the green meadow, Sirius remembered a little. He felt as if, inside his head, he was sitting in a green space that was vast, boundless, queer, and even more alive than the meadow in which his body sat. It was appalling. Yet, if he looked round the meadow, he knew that in time he could get to know every tuft and molehill in it. And, in the same way, he thought he might come to know the vaster green spaces inside his head.

“I don’t understand,” he thought, panting, with his tongue hanging out. “Why do those queer green spaces seem to be me?”

But his brain was not yet big enough to contain those spaces. It tried to close itself away from them. In doing so, it nipped the green vision down to a narrow channel, and urgent and miserable memories poured through. Sirius knew he had been wrongly accused of something. He knew someone had let him down terribly. How and why he could not tell, but he knew he had been condemned. He had raged, and it had been no use. And there was a Zoi. He had no idea what a Zoi was, but he knew he had to find it, urgently. And how could he find it, not knowing what it was like, when he himself was so small and weak that even a well-meaning being like Kathleen could pull him about on the end of a strap? He began whining softly, because it was so hopeless and so difficult to understand.

“There, there.” Kathleen gently patted him. “You are tired, aren’t you? We’d better get back.”

She got up from her damp hollow in the grass and fastened the lead to the red collar again. Sirius came when she dragged. He was too tired and dejected to resist. They went back the way they had come, and this time Sirius was not very interested in all the various smells. He had too much else to worry about.

As soon as Robin set eyes on Sirius, he said something. It was, “He’s pretty filthy, isn’t he?” but of course Sirius could not understand. Basil said something too, and Duffie’s cold voice in the distance said more. Kathleen hastily fetched cloths and towels and rubbed Sirius down and, all the while, Duffie talked in the way that made Sirius cower. He suddenly understand two things. One was that Duffie – and perhaps the whole family – had power of life and death over him. The other was that he needed to understand what they said. If he did not know what Duffie was objecting to, he might do it again and be put to death for it.

After that he fell asleep on the hearthrug with all four paws stiffly stretched out, and was dead to the world for a time. He was greatly in the way. Robin shoved him this way, Basil that. The thunderous voice made an attempt to roll him away under the sofa, but it was like trying to roll a heavy log, and he gave up. Sirius was so fast asleep that he did not even notice. While he slept, things came a little clearer in his mind. It was as if his brain was forced larger by all the things which had been in it that day.

He woke up ravenous. He ate his own supper, and finished what the cats had left of the second supper Kathleen had given them. He looked round hopefully for more, but there was no more. He lay sighing, with his face on his great clumsy paws, watching the family eat their supper – they always reserved the most interesting food for themselves – and trying with all his might to understand what they were saying. He was pleased to find that he had already unwittingly picked up a number of sounds. Some he could even put meanings to. But most of it sounded like gabble. It took him some days to sort the gabble into words, and to see how the words could be put with other words. And when he had done that, he found that his ears had not been picking up the most important part of these words.

He thought he had learnt the word walk straight away. Whenever Kathleen said it, he sprang up, knowing it meant a visit to the green meadow and the crawling water. In his delight at what that word meant, his tail took a life of its own and knocked things over, and he submitted to being fastened to the strap because of what came after. But he thought these pleasures were packed into a noise that went ork. Basil discovered this, and had great fun with him.

“Pork, Rat!” he would shout. “Stalk! Cork!”

Each time, Sirius sprang up, tail slashing, fox-red drooping ears pricked, only to be disappointed. Basil howled with laughter.

“No go, Rat. Auk, hawk, fork!”

In fact, Basil did Sirius a favour, because he taught him to listen to the beginnings of words. By the end of a week, Sirius was watching for the noise humans made by pouting their mouth into a small pucker. It looked a difficult noise. He was not sure he would ever learn to make it himself. But he knew that when ork began with this sound, it was real, and not otherwise. He did not respond to fork or talk and Basil grew quite peevish about it.

“This Rat’s no fun any more,” he grumbled.

Kathleen was relieved that Leo had almost stopped chewing things. Sirius was too busy learning and observing to do more than munch absently on his rubber bone. He ached for knowledge now. He kept perceiving a vast green something in himself, which was always escaping from the corner of his eye. He could never capture it properly, but he saw enough of it to know that he was now something stupid and ignorant, slung on four clumsy legs, with a mind like an amiable sieve. He had to learn why this was, or he would never be able to understand about a Zoi.

So Sirius listened and listened, and watched till his head ached. He watched cats as well as humans. And slowly, slowly, things began to make sense to him. He learnt that animals were held to be inferior to humans, because they were less clever, and smaller and clumsier. Humans used their hands in all sorts of devious, delicate ways. If there was something their hands could not do, they were clever enough to think of some tool to use instead. This perception was a great help to Sirius. He had odd, dim memories of himself using a Zoi rather as humans used tools. But animals could not do this. That was how humans had power of life and death over them.

Nevertheless, Sirius watched, fascinated, the way the cats, and Tibbles in particular, used their paws almost as cleverly as humans. Tibbles could push the cover off a meat dish, so that Romulus and Remus could make their claws into hooks and drag out the meat inside. She could pull down the catch of the kitchen window and let herself in at night if it was raining. And she could open any door that did not have a round handle. Sirius would look along his nose to his own great stumpy paws and sigh deeply. They were as useless as Duffie’s feet. He might be stronger than all three cats put together, but he could not use his paws as they did. He saw that this put him further under the power of humans than the cats. Because of their skill, the cats lived a busy and private life outside and inside the house, whereas he had to wait for a human to lead him about. He grew very depressed.

Then he discovered he could be clever too.

It was over the smart red jingly collar. Kathleen left it buckled round his neck after the first walk. Sirius hated it. It itched, and its noise annoyed him. But he very soon saw that it was more than an annoyance – it was the sign and tool of the power humans had over him. One of them – Basil for instance – had only to take hold of it to make him a helpless prisoner. If Basil then flipped his nose or took his bone away, it was a sign of the power he felt he had.

So Sirius set to work to make sure he could be free of that collar when he wanted. He scratched. And he scratched. And scratched. Jingle, jingle, jingle went the collar.

“Make that filthy creature stop scratching,” said Duffie.

“I think his collar may be on too tight,” said Robin. He and Kathleen examined it and decided to let it out two holes.

This was a considerable relief to Sirius. The collar no longer itched, though in its looser state it jingled more annoyingly than before. That night, after a little manoeuvring under Kathleen’s bed, he managed to hook it to one of Kathleen’s bedsprings and tried to pull it off by walking away backwards. The collar stuck behind his ears. It hurt. It would not move. He could not get it off and he could not get it on again. He could not even get it off the bedspring. His ears were killing him. He panicked, yelping and jumping till the bed heaved.

Kathleen sat up with a shriek. “Leo! Help! There’s a ghost under my bed!” Then she added, much more reasonably, “What on earth are you doing, Leo?” After that, she switched on the light and came and looked. “You silly little dog! How did you get into that pickle? Hold still now.” She unhooked Sirius and dragged him out from under the bed. He was extremely grateful and licked her face hugely. “Give over,” said Kathleen. “And let’s get some sleep.”

Sirius obediently curled up on her bed until she was asleep again. Then he got down and started scratching once more. Whenever no one was near, he scratched diligently, always in the same place, on the loops of the loose skin under his chin. It did not hurt much there and yet, shortly, he had made himself a very satisfactory raw spot.

“Your horse has his collar on too tight,” the thunderous voice told Kathleen. “Look.”

Kathleen looked, and felt terrible. “Oh, my poor Leo!” She let the collar out three more holes.

That night, to his great satisfaction, Sirius found he could leave the collar hanging on the bedspring, while he ambled round the house with only the quiet ticker-tack of his claws to mark his progress. It was not quite such an easy matter to get the collar on again. Kathleen woke twice more thinking there was a ghost under her bed, before Sirius thought of pushing his head into the collar from the other side. Then it came off the bedspring and on to his neck in one neat movement. He curled up on Kathleen’s bed feeling very pleased with himself.

This piece of cunning made Sirius much more confident. He began to suspect that he could settle most difficulties if he thought about them. His body might be clumsy, but his mind was quite as good as any cat’s. It was fortunate he realised this because, one afternoon when Kathleen, Robin and Basil were all out, long before Sirius had learnt more than a few words of human speech, Tibbles did her best to get rid of him for good.

Sirius, bored and lonely, drew himself quietly up on to the sofa and fell gingerly asleep there. He liked that sofa. He considered it unfair of the humans that they insisted on keeping all the most comfortable places for themselves. But he did not dare do more than doze. Duffie was moving about upstairs. It seemed to be one of the afternoons when she did not shut herself away in the shop and, Sirius had learnt by painful experience, you had to be extra wary on those days.

He had been dozing there for nearly an hour, when Romulus jumped on him. He hit Sirius like a bomb, every claw out and spitting abuse. Sirius sprang up with a yelp. He was more surprised than anything at first. But Romulus was fat and determined. He dug his claws in and stuck to Sirius’s back and Sirius, for a second or so, could not shake him off. In those seconds, Sirius became furiously angry. It was like a sheet of green flame in his head. How dared Romulus! He hurled the cat off and went for him, snarling and showing every pointed white tooth he had. Romulus took one look. Then he flashed over the sofa arm and vanished. Sirius’s teeth snapped on empty air. By the time he reached the carpet, Romulus was nowhere to be seen.

A bubbling hiss drew Sirius’s attention to Remus, crouched in the open doorway to the shop. Remus bared his teeth and spat. At that, Sirius’s rage flared vaster and greener still. He responded with a deep rumbling growl that surprised him nearly as much as it surprised Remus. A great ridge of fur came up over his back and shoulders and his eyes blazed green. Remus stared at this nightmare of eyes, teeth and bristle, and his own fur stood and stood and stood, until he was nearly twice his normal size. He spat. Sirius throbbed like a motor cycle and crept forward, slow and stiff-legged, to tear Remus to pieces. He was angry, angry, angry.

Remus only waited to make sure Sirius was indeed coming his way. Then he bolted without courage or dignity. He had done what his mother wanted, but not even for Tibbles was he going to face this nightmare a second longer than he had to. When Sirius reached the door of the shop there was no sign of Remus. There was only Tibbles, alone in the middle of a dusty floor.

Sirius stopped when his face was round the door. In spite of his rage, he knew something was not right here. This door should have been shut. Tibbles must have opened it. She must be trying to tempt him inside for reasons of her own. The prudent thing would be not to be tempted. But he had always wanted to explore the shop, and he was still very angry. To see what would happen, he pushed the door further open and let out another great throbbing growl at Tibbles.

At the sight and sound of him, Tibbles became a paper-thin archway of a cat, and her tail stood above in a desperate question mark. Was this a puppy or a monster? She was terrified. But she stood her ground because this was her chance to get rid of it.

Her terror gave Sirius rather an amusing sense of power. Slow and stiff-legged, he strutted into the room. Tibbles spat and drifted away sideways, so arched that she looked like a piece of paper blowing in the wind. Sirius saw she wanted him to chase her. Just for a moment, he did wonder how it would feel to take her arched and narrow back between his teeth and shake his head till she snapped, but he was sure she would jump out of reach somewhere before he could catch her. So he ignored her. Instead, he swaggered across the dusty floor to look at the objects piled by the walls and stacked on the shelves.

He sniffed them cautiously. What were these things? As curiosity gained the upper hand in him, his growl died away and the hair on his back settled down into glossy waves again. The things had a blank, muddy smell. Some were damp and pink, some pale and dry, some again shiny and painted in ugly grey-greens. They were something like the cups humans drank out of, and he thought they might be made of the same stuff as the dish labelled DOG in which Kathleen gave him his water. But Sirius could not have got his tongue into most of them. No human could have drunk out of any.

Then he remembered the thing on the living-room mantelpiece Kathleen had smashed that morning when she was dusting. It had held one rose. Duffie had been furious.