По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

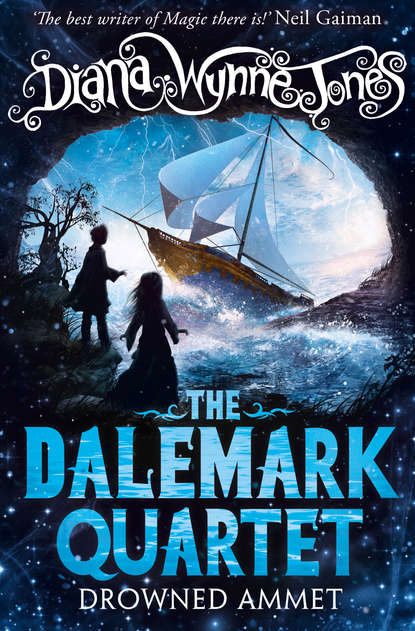

Drowned Ammet

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You sound just like your dad,” Milda said coldly. “Let me tell you, those oysters were a bargain at two silver, and you ought to be grateful.”

“Two silver!” Mitt raised both his chilblained hands to the blotchy ceiling. “That’s no bargain. That’s daylight robbery, that is!”

Mitt and Milda – and the ants – had oysters for supper and for breakfast, and after that they both felt unwell, although the ants seemed as lively as ever. Ham kindly helped Mitt throw the rest of the tub into the harbour.

“And she went and paid two silver for them!” Mitt groaned.

“Don’t be too hard on her. She’s used to better things,” Ham said. “She’s a lovely good woman, she is.”

Mitt stared at him. “If I didn’t feel sick as a dog already,” he said, “I would after I heard you say that!” And he went back upstairs, muttering, “Lovely good woman!” to himself in the greatest disgust. Of course he knew his mother was still young and pretty, in spite of that hateful crease on her face where her dimple should have been, and he knew she was not like those other ladies in the tenement who were always down on the waterfront, making up to the sailors whenever a ship came in, but for Ham to say that! Mitt had never noticed that Ham deeply admired Milda. Ham was too slow and shy to let Milda know it. And Mitt’s feeling was that all women were born stupid and grew worse.

Alda, Siriol’s wife, was the worst of the lot. Mitt supposed he should be thankful that his mother did not spend all her money on arris, the way Alda did. Alda was usually too drunk to sell the fish Siriol, Ham and Mitt had caught. She sat on a barrel at the corner of the stall, while Lydda stood dumbly behind the heaps of fish, letting people have them too cheap. It pained Mitt to his soul. After all their trouble, out half the night pulling in fish in the drizzling rain, a rich merchant’s housekeeper or a mincing man from the Palace had only to appear and point to a pile of sweet whitebait, and Lydda would humbly halve the price. It was not fair. The ones who could afford to pay the full price always got it cheap. But that was Holand all over.

At length, Lydda’s spineless meekness was more than Mitt could bear. If the fish was to go cheap, he felt it should go cheap to the right people. He elbowed Lydda aside and tried selling the fish himself.

“Hadd, Hadd, haddock!” he shouted. “Fit for an earl, and dirt cheap too!” When people stopped and stared, Mitt took up a haddock and waved it about. “Hadd,” he said, “ock. Come on. He won’t eat you. You eat him.” He picked up an eel in the other hand. “And here’s an earl – I mean a Harl – I mean an eel – for sale. Who wants a nice fresh Harl for supper?” It was great fun, and it sold a lot of fish.

After that Mitt always sold the fish. Lydda weighed and wrapped it, while her mother sat on her tub chuckling at Mitt and breathing arris fumes over the customers. Mitt was often very tired. His hands were chapped and covered with little cuts from the fish scales, winter and summer, but it was worth it, just to be able to shout rude things about Hadd.

“You want to watch it, Mitt,” Siriol said whenever he heard Mitt’s sales talk. But he let Mitt go on. After all, there was always a laughing crowd round the stall, buying fish. Even the Palace lackeys sniggered as they bought.

Then one day, as soon as Flower of Holand was out of the harbour and no one could overhear, Siriol amazed Mitt by asking him if he wanted to join the Free Holanders.

“I’ll have to think,” Mitt said. And he missed selling the fish that next morning, in order to hurry home and ask Milda what he ought to do, before she went to work. “I can’t join, can I?” he said. “Not after what they did to Dad?”

But Milda went dancing round the room, her skirts held out and her earrings swinging, and her dimple deep and clear. “This is your chance!” she said. “Don’t you see, Mitt? This is your chance to get back at them at last!”

“Oh yes,” said Mitt. “I suppose it is and all.”

So Mitt became a Free Holander, and great fun it was too. At first it was simply the great fun of being in the secret, with, behind that, the further secret that he was only in it to get revenge for his father. Mitt grinned to himself at both secrets all through long, boring watches when he was alone at Flower of Holand’s tiller, and the stars wheeling overhead seemed to glimmer with sheer glee.

“Ah, shut up, he’s useful!” Siriol said to Ham when Ham protested. “Who’s going to bother with a lad who looks just like all the other kids? People think boys don’t count. Look at the way he gets away with selling fish. He’s safer than what we are.”

Taking messages for the Free Holanders was pure bliss to Mitt. He revelled in going unnoticed through the crowded streets. It was good to be small and ordinary-looking, so that he could get the better of Harchad’s soldiers and spies. He would memorise the message carefully and slip off after selling the fish, mingle with the crowd in this street, watch a fight in that alley, loiter round the barracks, joking with the soldiers, and still go unsuspected. He was Mitt of the free soul, who did not know the meaning of fear. And the greatest fun of all was when he chanced to be in a street while soldiers stopped off both ends of it and questioned everyone in it about their business.

Harchad ordered this done quite often, as much to keep people properly subdued as to catch revolutionaries. In a tense silence, broken only by the clopping of soldiers’ boots, his men would go from person to person, searching bags and pockets and asking each one what he was doing in this street. Mitt delighted in inventing business. He loved giving his name. It was marvellous to have the commonest name in Holand. Mitt, with perfect truth, could call himself Alham Alhamsson, Ham Hamsson, Hammitt Hammittsson, and Mitt Mittsson, or any combination of those that he fancied. He enlivened boring hours of fishing by thinking up new ways to fool Harchad’s men.

The only trouble about being a Free Holander was that Mitt did not understand what the meetings were about. Once the novelty wore off, they bored him to tears. They would sit in someone’s shed or attic, often without a candle even, and Siriol would start by talking of tyranny and oppression. Then Dideo would say that the leaders of the future were coming from below. Below what? Mitt wondered. Someone would tell a long tale of Hadd’s injustice, and someone else would whisper things about Harchad. And sooner or later Ham would be thumping the table and saying, “We look to the North, we do. Let the North show its hand!”

The first time Ham said this, Mitt felt a shiver of excitement. He knew Ham could be arrested for saying it. But Ham said it so often that Mitt lost interest. He found he was using the meetings to make up sleep in. He never got enough sleep in those days.

Mitt felt this would not do. If he was to get his revenge on the Free Holanders, he needed to know what they were up to. “What do they think they’re doing?” he asked Milda. “It’s all looking to the North, or whisper, whisper, about Harchad, or tyranny and that. What’s it about?”

Milda looked nervously round the room. “Hush. They’re getting at rebellion and uprising – I hope.”

“They don’t get at it very fast,” Mitt said discontentedly. “There’s no plans at all. I wish you could come to meetings and see if you could make some sense of them.”

Milda laughed. “I might – I bet they wouldn’t have me, though.”

When Milda laughed, the crease on her face gave way to a dimple again. It was a thing Mitt always tried to encourage if he could. So he said, “I bet they would have you. You could stir them up a bit and get them to come out with something. I’m sick of old tyranny and the rest!” And since this made Milda smile broadly, Mitt did his best to keep her smiling. “Tell you what,” he said. “While I’m getting back at them for informing, I’d like to get back at old Hadd too. I’d like to give him what for, because of him trampling you underfoot all these years.”

“What a boy you are!” said Milda. “You don’t know what fear is, do you?”

After that, it was understood between Mitt and Milda that the mission of Mitt’s life was a double one. He was to break the Free Holanders and rid the world of Earl Hadd. Mitt was sure he could do it. So was Milda.

Milda joined the Free Holanders too. Mitt was delighted. He had high hopes of it. Milda came to meetings, and she talked as eloquently as anyone there. She loved to talk. She loved leaning forwards over the secretive night-light and seeing everyone’s listening faces shadowy and attentive. But the sole result was that Milda became as ardent a freedom fighter as anyone there. She talked revolution to Mitt whenever he was at home.

“Flaming Ammet!” Mitt said disgustedly. “It’s like being at a meeting all the time now!”

All the same, Milda’s talk did make things clearer to Mitt. He was soon able to talk of oppression and uprising, tyranny and leadership from below, and feel he knew what it meant. And when he had leisure to think – which he sometimes did while Flower of Holand ploshed her sturdy way to the fishing grounds – he decided that what it amounted to was that there were two parts to Dalemark: the North, where people were mysteriously free and happy, and the South, where the earls and the rich people were free and happy enough, but where they made darned sure that ordinary people like Mitt and Milda were as unhappy as possible.

Right, Mitt said to himself. I reckon that sums it up. Now let’s get busy and do something about it.

But the Free Holanders seemed simply content to talk, and Mitt became increasingly annoyed by them. He was very pleased when another secret society actually killed four of Harchad’s spies. Siriol was not. He told Mitt, with a glum sort of gladness, that things would be very much worse now. And they were.

Harchad imposed a curfew. Anyone found in the streets after dark was marched away and never seen again. Siriol forbade Mitt to carry messages during that time. Mitt did not quite understand why he should not.

Then a thief on the waterfront tried to rob a man. He knocked the man down and was taking his money when he found a gold button with the wheatsheaf crest of Holand on it, hidden in the man’s coat. The thief knew it was the badge Harchad gave all his spies, and he was so frightened that he jumped into the harbour and was drowned. Mitt did not understand this story at all.

“Well, if you don’t, I’m not telling you,” was all Siriol would say.

Then Earl Hadd quarrelled with four other earls at once. Everyone in Holand groaned. Much as they detested Hadd, they almost admired him for being so very quarrelsome. “Fallen out with Earl Henda again, has he?” the women in Milda’s sewing shop would say. “Honestly, I never knew anyone like him!” This time, however, Hadd fell out not only with Henda, but with the Earls of Canderack, Waywold and Dermath too. And so powerful were these Earls, and owned so much of South Dalemark between them, that there was some doubt in Holand whether Hadd could hold his own against them all.

“Bitten off more than he can chew this time for sure, the old sinner,” Dideo said to Mitt. “Maybe this is where the Free Holanders get their chance.”

Mitt hoped so. But Harl, Hadd’s eldest son, managed to put himself into Hadd’s good books by suggesting a way to deal with the four Earls. Harl, fat and indolent though he was, could sometimes be seen with his brother Navis and a crowd of beaters, servants and dogs, walking over the Flate and shooting birds with a long silver-inlaid fowling piece. Harl was allowed to use a gun, being an earl’s son. No one else was, apart from lords and hearthmen, because there had been so many uprisings in the South. Big ships carried cannon, as a protection against the ships of the North, but guns were other wise banned. But, said Harl, why not give all the soldiers guns as well? That would make the four Earls think twice before attacking Holand.

Hadd agreed that it would. And that put paid to the hopes of Mitt and the Free Holanders. Up went rents and taxes and harbour dues. The people of Holand admitted grudgingly that Hadd was up to everything, even while they groaned.

“It’s not right,” said Ham. “Give Harchad’s men guns and they’ll be ten times worse than they are now. But you have to admire Hadd. Fair play.”

But Hadd took other precautions too. The Earl of Canderack, since most of the coast north of Holand was his, owned a fair-size fleet he could send against Holand if necessary. Holand also had its fleet. But to be on the safe side, Hadd betrothed his granddaughter Hildrida to the Lord of the Holy Islands, north of Canderack. The ships of the Holy Islands were famous. As Siriol remarked to Ham, the Holy Islands fleet was probably the main reason why the North had not long since conquered the South and brought freedom to everyone. Milda, as she sewed with three other women at a great bedspread to be covered with blue and gold roses, thought of it from another point of view. One of the women said that Lithar, Lord of the Holy Islands, was twenty years old. And, another added, Hildrida Navisdaughter could only be about nine.

Milda remembered she had once been interested in Navis and his family. “Then in that case I don’t think it’s fair at all!” she said warmly.

(#ulink_6a459ffb-e3da-5433-a43d-239321fa8175)

IT DID NOT seem fair to Hildrida Navisdaughter either. She thought at first she was in trouble. She and her brother, Ynen, had gone sailing. They had been tired of being told they were too young to go out in a boat alone and of being taken tamely up and down the coast by the sailors the Earl employed to sail his family. Ynen had wanted to sail a boat himself. So they slipped away and borrowed their cousins’ yacht. It had been splendid fun, and very frightening too. Ynen had nearly laid the boat on her side, just outside the West Pool, before he got used to the wind. And they had twice found themselves nearly aground in the shoals beyond. But they had managed. They had brought the yacht back and not even bumped the jetty.

Then, as soon as she reached the Palace, Hildy was told her father wanted to see her. Naturally she thought he had found out about the sailing.

Too bad for him! Hildrida thought, while she was having a good dress put on and her windblown black hair brushed. I shall be very angry. I shall say we’re never allowed to do anything. I shall say it’s my fault, and I shan’t let him send for Ynen. And I’ll tell him that it doesn’t matter whether we drown or not. It’s not as if we were important.

The lady-in-waiting who led Hildrida by her hand through the lofty corridors to Navis’s rooms rather thought Hildrida must have found out what was in store for her. She had never seen her so white and stormy. The lady-in-waiting was glad she was not in Navis’s shoes.

Navis was well aware that his daughter had an awkward personality. He had taken refuge in a book. When Hildy was shown in, she found him sitting on the window seat, with his calm profile outlined against the Flate beyond the window, and his eyes on a song by the Adon. She was exasperated. The ladies-in-waiting told her that Navis was still grieving for her dead mother, but Hildy found that hard to believe. To her mind, Navis was the coldest and laziest person she knew.

“I’m here,” she said piercingly, to stir him up a bit. “And I’m not sorry.”