По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

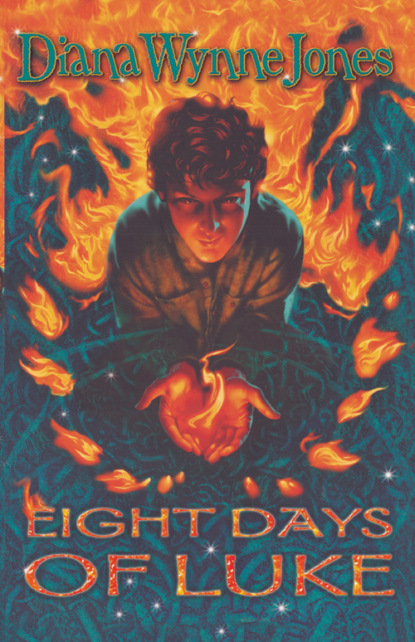

Eight Days of Luke

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“All my horrible relations,” David said. It was a relief to talk about it. He told Luke how his relations did not want him, how they were planning to send him to Mr Scrum so that they could go to Scarborough, about Mrs Thirsk, the food and the chewing gum, and about the row at lunch. Luke listened sympathetically, but it was when David came to the cursing part that he grew really interested.

“What did you say?” he asked. “Can you remember?”

David thought, and was forced to shake his head. “No. It’s gone. But I suppose it was some kind of curse if it knocked the wall down.”

Luke smiled. “No. It wasn’t a curse.”

“How do you know? It brought out a load of snakes too, didn’t it?”

“But it wasn’t a curse, all the same,” said Luke.

David was a little annoyed. For one thing, Luke could not possibly know, and, for another, although it would have been a relief not to have uttered a curse after all, it was plain to David that his words had had a powerful effect of some kind. “What was it then?” he said challengingly.

“Unlocking words. The opposite of a curse, if you like,” Luke said, as if he really knew. David said nothing. He thought Luke was trying to make him feel less guilty about the ruin they were sitting on. Luke smiled. “You don’t believe me, do you?” David shook his head. “Oh well,” said Luke. “But they were, and I’m truly grateful to you. You let me out of a really horrible prison.” He smiled happily and pointed with one slightly blistered finger to the ground under the wall.

This was too much for David, who, after all, had been there to see that nothing but flames and snakes had come from the ground. “Pull the other leg,” he said.

Luke looked at him with one eyebrow up and a mischievous, calculating look on his filthy face. He seemed to be deciding just how much nonsense David could be brought to swallow. Then he laughed.

“Have it your own way,” he said. “But I am grateful, and I’ll do anything I can in return.”

“Thanks,” David said disbelievingly. “Then I suppose you can help me stand this wall up again.”

Luke looked at David in that shrewd and mischievous way again. “I might,” he said. “Shall we see what we can do?”

“Oh, do let’s,” David said sarcastically.

Luke jumped up briskly. “Come on, then. You take the other end of this and help me lift it.” He stooped and put his hands to a section of brickwork, where the wall had come down still cemented together. “Come on,” he said. “Don’t look so glum about it.”

So David, feeling hopeless about it, got up slowly and wandered to the other end of the joined piece of wall. He put his hands to it and found the bricks coming loose as he touched them.

“Heave!” Luke said cheerfully.

David heaved, not very hard. But he must have heaved harder than he thought, because he managed to raise the whole section. Luke lifted his end, and together they carried a whole chunk of wall, grinding and bending, and laid it down in one piece by the compost heap.

“There, you see?” said Luke, and went jumping gaily back across the bricks. “Now this bit.”

In a remarkably short time, they had all the complete sections of wall laid out in order on the gravel. When these were moved, they found there had been a tree growing up against the back of the wall – part of the neat orchard – and the wall had crushed it as it went over. They looked at it, Luke laughing and David glum. Luke shook his head.

“It’s dead,” said David.

“Yes, but we can fake it a bit,” Luke said. “You pull that branch straight.”

They spread the tree out until it looked the right shape for a tree again. Then Luke lifted it in his arms and thumped the broken trunk into the soft ground until it stood upright. Its leaves were withering and wilting still, but it looked as if it were growing.

“Can’t bring the dead to life, I’m afraid,” said Luke, “but they might think it died from natural causes, with luck.”

Then they rebuilt the wall. David had never imagined it could be so easy. True, they worked hard and sweat trickled through the dirt on their faces, but they laughed and whistled as well, and the wall grew in leaps and bounds.

As they worked, David came to like Luke more and more. He was fun. He made jokes all the time, and no difficulty seemed to dismay him. Some of his jokes were complete nonsense, mostly because he chose to keep up the pretence that David had let him out of prison. “My chains,” he said, as they staggered under the largest section of wall, “were a good hundred times heavier than this.” Then again, when they got to the most difficult part, which was slotting the newly rebuilt wall into the jagged ends of the walls at the sides of the garden, Luke said something odd. David was doing the slotting, while Luke held the wall tilted for him. He could see Luke’s muscles standing out in knots.

“Are you sure you can hold it?” David asked.

“Nothing like so heavy as a bowl of venom,” Luke panted cheerfully. David laughed.

Once the wall was slotted in, they were finished. It was not perfect. The upper courses of bricks wandered up and down a little, and because they had used no cement, there were places where you could look through to the orchard. But it stood solidly. David and Luke were very proud of it.

“Not bad, considering neither of us ever built a wall before,” Luke said. “What shall we do now?”

David looked at his watch and found it was nearly supper time. “I shall have to go in,” he said mournfully. “They get furious if I’m late.” He was very dejected. He remembered he was in disgrace and about to be sent to Mr Scrum on Tuesday. It was too bad, now that he had met Luke. “Can you come out after supper?” he asked, thinking he must see as much of Luke as he could while he had the chance.

“Of course,” said Luke. “Whenever you want. Just kindle a flame and I’ll be with you.”

“Meet you here then,” said David.

“As you like,” said Luke. David turned to go and Luke, laughing, but trying to look solemn, raised one hand like a Redskin salute. “Farewell, oh my benefactor,” said he.

“Oh do shut up about that!” David said, and ran down the garden laughing.

CHAPTER FOUR The Third Trouble (#ulink_db186a8d-043e-5fad-b1fe-c5ee0242ae56)

David was filthy. He had to wash and climb into more of Cousin Ronald’s wide cast-offs before he dared to go down to supper. The odd thing about washing in a hurry is that soap and water only loosen the dirt. Most of it comes off on the towel afterwards. David looked rather nervously at the reddish-black smears on Mrs Thirsk’s bright white towel, but he was in too much of a hurry to do anything about it. The gong had gone before he started to wash.

He hurried downstairs, thinking about Luke and Luke’s odd jokes. If Luke had not come along, there was no doubt David would at this moment be crawling downstairs in the most hideous state of guilt, wondering how he was going to confess to having cursed a wall down. As it was, he felt much better. Rebuilding the wall had wiped away his misery and also the horror of the way the curse had worked. He thought of the flames and the snakes, but all they did was to remind him of Luke’s joke about kindling a flame. David grinned as he came to the bottom of the stairs, because someone – Astrid probably – had left a box of matches on the stand beside the gong. David slipped them into his pocket as he passed. If Luke wanted him to strike a match as a signal, then he would. But it was no good asking for matches. That would only remind his relations to forbid him to have them.

He went into the dining room. Astrid was saying, “And my leg never left me in peace, the whole afternoon.”

“Both my legs,” said Uncle Bernard. Then he saw David in the doorway and abandoned the contest. David walked to his place and sat down in a silence heavier and nastier than any he had known. It was clear the row was still going on. Unless, David thought rather nervously as he picked up his soup spoon, they had found out about the wall and were angry about that now. The soup was burnt. David could see black bits floating in it. It tasted burnt.

Cousin Ronald broke the silence at last by saying reproachfully, “We are waiting to hear you say sorry, David.”

“Sorry,” David said, wondering why they could not have told him that straight away.

There was another heavy silence.

“We want to hear you apologise,” said Aunt Dot.

“I apologise then,” said David.

“I don’t call that an apology,” said Uncle Bernard.

“Well, I said sorry and I said I apologise,” David pointed out. “What else do you want me to say?”

“You might take back your words,” suggested Astrid.

“All right. I take them back,” David said, hoping this would now mean peace. But he thought as he said it that it was just like Astrid to say the silliest thing of the lot. “How can you take back words anyway? I mean, once you’ve said them they’ve gone, haven’t they, and—?”

“That will do,” said Cousin Ronald. There was more silence, broken by the reluctant clinking of spoons, during which David began to wish that his curse had really been a curse and working at this moment. Then Cousin Ronald cleared his throat and said, “David, there is something we have to tell you. We have decided, solely on your account, not to go to Scarborough after all. We shall stay here, and you shall stay with us.”