По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

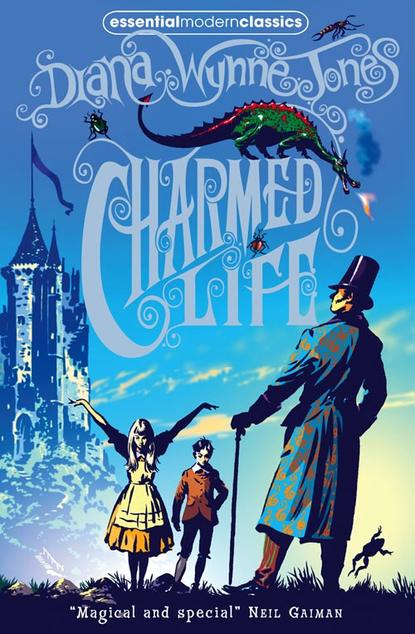

Charmed Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Oh, but I can’t do that,” Chrestomanci said absentmindedly. “Sorry and so on.”

Gwendolen stamped her foot. It made no noise to speak of, even there on the marble floor, and there was no echo. Gwendolen was forced to shout instead. “Why not? You must, you must, you must!”

Chrestomanci looked down at her, in a peering, surprised way, as if he had only just seen her. “You seem to be annoyed,” he said. “But I’m afraid it’s unavoidable. I told Michael Saunders that he was on no account to teach either of you witchcraft.”

“You did! Why not?” Gwendolen shouted.

“Because you were bound to misuse it, of course,” said Chrestomanci, as if it were quite obvious. “But I’ll reconsider in a year or so, if you still want to learn.” Then he smiled kindly at Gwendolen, obviously expecting her to be pleased, and drifted dreamily away down the marble stairs.

Gwendolen kicked the marble balustrade and hurt her foot. That sent her into a rage as strong as Mr Saunders’. She danced and jumped and shrieked at the head of the stairs, until Cat was quite frightened of her. She shook her fist after Chrestomanci. “I’ll show you! You wait!” she screamed. But Chrestomanci had gone out of sight round the bend in the staircase and perhaps he could not hear. Even Gwendolen’s loudest scream sounded thin and small.

Cat was puzzled. What was it about this Castle? He looked up at the dome where the light came in and thought that Gwendolen’s screaming ought to have echoed round it like the dickens. Instead, it made a small, high squawking. While he waited for her to get her temper back, Cat experimentally put his fingers to his mouth and whistled as hard as he could. It made a queer blunt noise, like a squeaky boot. It also brought the old lady with the mittens out of a door in the gallery.

“You noisy little children!” she said. “If you want to scream and whistle, you must go out in the grounds and do it there.”

“Oh, come on!” Gwendolen said crossly to Cat, and the two of them ran away to the part of the Castle they were used to. After a bit of muddling around, they discovered the door they had first come in by and let themselves outside through it.

“Let’s explore everywhere,” said Cat. Gwendolen shrugged and said it suited her, so they set off.

Beyond the shrubbery of rhododendrons, they found themselves out on the great smooth lawn with the cedar trees. It spread across the entire front of the newer part of the Castle. On the other side of it, Cat saw the most interesting high sun-soaked wall, with trees hanging over it. It was clearly the ruins of an even older castle. Cat set off towards it at a trot, past the big windows of the newer Castle, dragging Gwendolen with him. But, half-way there, Gwendolen stopped and stood poking at the shaved green grass with her toe.

“Hm,” she said, “Do you think this counts as in the Castle?”

“I expect so,” said Cat. “Do come on. I want to explore those ruins there.”

However, the first wall they came to was a very low one, and the door in it led them into a very formal garden. It had broad gravel paths, running very straight, between box hedges. There were yew trees everywhere, clipped into severe pyramids, and all the flowers were yellow, in tidy clumps.

“Boring,” said Cat, and led the way to the ruined wall beyond.

But once again there was a lower wall in the way, and this time they came out into an orchard. It was a very tidy orchard, in which all the trees were trained flat, to stand like hedges on either side of the winding gravel paths. They were loaded with apples, some of them quite big. After what Chrestomanci had said about scrumping, Cat did not quite dare pick one, but Gwendolen picked a big red Worcester and bit into it.

Instantly, a gardener appeared from round a corner and told them reproachfully that picking apples was forbidden.

Gwendolen threw the apple down in the path. “Take it then. There was a maggot in it anyway.”

They went on, leaving the gardener staring ruefully at the bitten apple. And instead of reaching the ruins, they came to a goldfish pond, and after that to a rose garden. Here Gwendolen, as an experiment, tried picking a rose. Instantly, another gardener appeared and explained respectfully that they were not allowed to pick roses. So Gwendolen threw the rose down too. Then Cat looked over his shoulder, and discovered that the ruins were somehow behind them now. He turned back. But he still did not seem to reach them. It was nearly lunch time before he suddenly turned into a steep little path between two walls and found the ruins above him, at the top of the path.

Cat pelted joyfully up the steep path. The sun-soaked wall ahead was taller than most houses, and there were trees at the top of it. When he was close enough, Cat saw that there was a giddy stone staircase jutting out of the wall, more like a stone ladder than a stair. It was so old that snapdragons and wallflowers had rooted in it, and hollyhocks had grown up against the place where the stair met the ground. Cat had to push aside a tall red hollyhock in order to put his foot on the first stair.

No sooner had he done so than yet another gardener came puffing up the steep path. “You can’t go there! That’s Chrestomanci’s garden up there, that is!”

“Why can’t we?” said Cat, deeply disappointed.

“Because it’s not allowed, that’s why.”

Slowly and reluctantly, Cat came away. The gardener stood at the foot of the stair to make sure he went. “Bother!” Cat said.

“I’m getting rather sick of Chrestomanci forbidding things,” said Gwendolen. “It’s time someone taught him a lesson.”

“What are you going to do?” said Cat.

“Wait and see,” said Gwendolen, pressing her lips together in her stormiest way.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_285caa06-2db0-51a4-b4b8-8aa41555be32)

Gwendolen refused to tell Cat what she was going to do. This meant that Cat had rather a melancholy time. After a wholesome lunch of swede and boiled mutton, they had lessons again. After that, Gwendolen ran hastily away and would not let Cat come with her. Cat did not know what to do.

“Would you care to come out and play?” Roger asked.

Cat looked at him and saw that he was just being polite. “No thank you,” he said politely. He was forced to wander round the gardens on his own. There was a wood lower down, full of horse chestnuts, but the conkers were not nearly ripe. As Cat was half-heartedly staring up into one, he saw there was a tree-house in it, about halfway up. This was more like it. Cat was just about to climb up to it, when he heard voices and saw Julia’s skirt flutter among the leaves. So that was no good. It was Julia and Roger’s private tree-house, and they were in it.

Cat wandered away again. He came to the lawn, and there was Gwendolen, crouching under one of the cedars, very busy digging a small hole.

“What are you doing?” said Cat.

“Go away,” said Gwendolen.

Cat went away. He was sure what Gwendolen was doing was witchcraft and had to do with teaching Chrestomanci a lesson, but it was no good asking Gwendolen when she was being this secretive. Cat had to wait. He waited through another terrifying dinner, and then through a long, long evening. Gwendolen locked herself in her room after dinner and told him to go away when he knocked.

Next morning, Cat woke up early and hurried to the nearest of his three windows. He saw at once what Gwendolen had been doing. The lawn was ruined. It was not a smooth stretch of green velvet any longer. It was a mass of molehills. As far as Cat could see in both directions, there were little green mounds, little heaps of raw earth, long lines of raw earth and long green furrows of raised grass. There must have been an army of moles at work on it all night. About a dozen gardeners were standing in a gloomy huddle, scratching their heads over it.

Cat threw on his clothes and dashed downstairs.

Gwendolen was leaning out of her window in her frilly cotton nightdress, glowing with pride. “Look at that!” she said to Cat. “Isn’t it marvellous! There’s acres of it, too. It took me hours yesterday evening to make sure it was all spoilt. That will make Chrestomanci think a bit!”

Cat was sure it would. He did not know how much a huge stretch of turf like that would cost to replace, but he suspected it was a great deal. He was afraid Gwendolen would be in really bad trouble.

But to his astonishment, nobody so much as mentioned the lawn. Euphemia came in a minute later, but all she said was, “You’ll both be late for your breakfast again.”

Roger and Julia said nothing at all. They silently accepted the marmalade and Cat’s knife when he passed them over, but the sole thing either of them said was when Julia dropped Cat’s knife and picked it up again all fluffy. She said, “Bother!” And when Mr Saunders called them through for lessons, the only things he talked about were what he was teaching them. Cat decided that nobody knew Gwendolen had caused the moles. They could have no idea what a strong witch she was.

There were no lessons after lunch that day. Mr Saunders explained that they always had Wednesday afternoons off. And at lunchtime, every molehill had gone. When they looked out of the playroom window, the lawn was like a sheet of velvet again.

“I don’t believe it!” Gwendolen whispered to Cat. “It must be an illusion. They’re trying to make me feel small.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: