По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

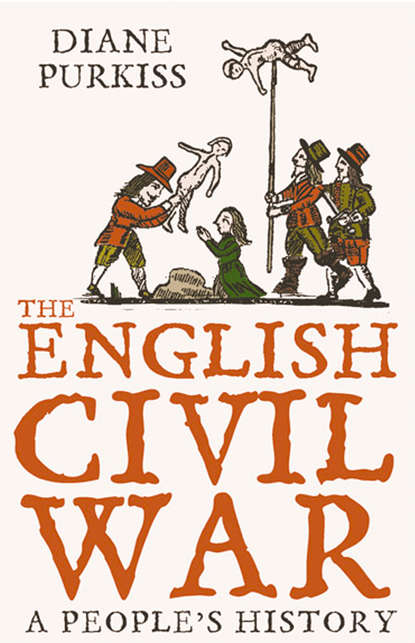

The English Civil War: A People’s History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Anna Trapnel’s religious background supported her notion that she was worthless, while feeding her longing for compensation through being specially chosen by God. This drama had its dark side. During a prolonged spiritual depression, Anna contemplated murder and suicide, but on New Year’s Day 1642 she heard John Simpson preaching at All Hallows the Great, and there was an immediate (and joyful) conversion. The godly typically went through these periods of joy and misery; they were an intrinsic part of Calvinist salvation.

Simpson was relatively young, in his thirties, and another of the St Dunstan’s lecturers. A man of passionately independent views, he was removed from his lectureship in St Aldgate in 1643, and banned from preaching. He was soon in trouble again for asserting, allegedly, that Christ was to be found even ‘in hogs, and dogs, or sheep’. In 1647 Simpson became pastor of the gathered congregation at All Hallows the Great. He was also to fight against Prince Charles at Worcester in 1650. Unlike many radicals, Simpson placed no trust in Oliver Cromwell as the instrument of God. He reported visions in which God had revealed to him Cromwell’s lust for power and his impending ruin. He became a leader of the Fifth Monarchists, a group who believed themselves the elect and the end of the world near. Many contemporaries were bewildered by Simpson’s volatile and passionate nature and thought him mad. But everyone recognized his power as a preacher. In the heady atmosphere of freedom from guild restraints, immigrants bringing novel ideas, the wildness of the East End, and the religious adventure of St Dunstan’s, the unthinkable was soon being thought, and not only by Trapnel. Joan Sherrard, of Anna Trapnel’s parish, said in 1644 that the king was ‘a stuttering fool’ and asked passionately ‘is there never a Fel[t]on yet living? [Felton was the man who had assassinated the Duke of Buckingham.] If I were a man, as I am a woman, I would help to pull him to pieces.’ It was the kind of thing one housewife might shout at another in a noisy high street. It was unimaginable at court, only a few miles distant.

The world was an altogether different place for noblewoman Lucy Hay. West End, not East End; magnificent houses, not wooden terraces; shopping, not working; the court, not the pulpit – though Lucy was religious, and militantly Protestant at that. Lucy Hay was England’s salonnière, a beautiful woman who enjoyed politics, intrigue, plots, but also intellectual games, poetry, love affairs (intellectual, and probably occasionally physical), fashion, clothes and admiration. She was one of Henrietta Maria’s closest and most trusted friends, but also her competitor and sometime political enemy. Her world was more introverted than Trapnel’s, with the obsessive cliquishness of an exclusive girls’ school. But like many a pupil, Lucy struggled not only to dominate it, but also to find ways to widen it.

Her success was founded on her face. She was such a beauty that when she contracted smallpox, the whole court joined forces to write reassuring letters to her husband, telling him that she was not in danger of losing her looks. She asked for and received permission to wear a mask on her return to court, until her sores were entirely healed; when she removed it, people said that she was not only unblemished, but lovelier than ever.

Lucy Hay came from an extraordinary family, the Percys, Earls of Northumberland, a family of nobles always powerful in dissent. Her great-uncle was a leader in the Northern Earls rebellion, beheaded for it in 1572, and her father was imprisoned in the Tower for suspected involvement in the Gunpowder Plot. The Percys were a noble family inclined to see the monarch of the day as only primus inter pares, and to act accordingly. Lucy’s father was known as ‘the wizard earl’ because of his interest in magic, astronomy and mathematics – he was so interested in numbers that he kept three private mathematicians at his side. Hard of hearing, remote of bearing, and often shy, he was also a passionate gambler, and his contemporaries found him difficult to understand. His wife, Dorothy Devereux, was the sister of the Earl of Essex who was Elizabeth’s favourite late in her life, and Dorothy, too, was loved by the queen. But like the Percys, the Devereux found it difficult to accept the absolute sovereignty of the monarch. They had their own power and they wanted it respected.

Within the marriage this mutual strong-mindedness did not make for harmony. The couple separated, and after Elizabeth had brought about a reconciliation which produced a male heir, fell out again. There was no divorce, but they lived apart. Henry Percy did not take to James I. He disliked in particular the many Scots James had brought with him and may have seen their promotion to the nobility as a threat to established families like his own. In the autumn of 1605, he retired to Syon House to think more about numbers and less about politics. His choice of retreat points to the way the Percys had come to see themselves as a southern family; there was no question of a retreat to the north, to the family seat at Alnwick.

This mathematical pastoral was, however, threatened in two ways. First, the Gunpowder Plot exploded, and Northumberland’s kinsman Thomas Percy, four years his elder and one of the chief conspirators, had dined on 4 November with Northumberland at Syon House. Though not a papist, Northumberland was a known Catholic sympathizer, who had tried to secure the position of Catholics with James when he became king. Although he had few arms, horses or followers at Syon, and had known none of the conspirators excepting Percy, he was sent to the Tower on 27 November. He tried to excuse himself in a manner which reveals the Percy attitude to affairs of state: ‘Examine’, he said, ‘but my humours in buildings, gardenings, and private expenses these two years past.’ He was not believed. On 27 June 1606 he was tried in the Court of Star Chamber for contempt and misprision of treason. At his trial, he was accused of seeking to become chief of the papists in England; of failing to administer the Oath of Supremacy to Thomas Percy. He pleaded guilty to some of the facts set forth in the indictment, but indignantly repudiated the inferences placed upon them by his prosecutors. He was sentenced to pay a fine of 30,000 pounds, to be removed from all offices and places, to be rendered incapable of holding any of them hereafter, and to be kept a prisoner in the Tower for life. Voluntary exile had become forced imprisonment. The hand of royalty was heavy.

Northumberland protested to the king against the severity of this sentence, but his cries went unheard. Much more significantly, and perhaps more effectively, his wife Dorothy appealed to the queen, Anne of Denmark, who took a sympathetic interest in his case. This may have been where Lucy learned that women have power, that one can work through queens where kings are initially deaf. The king nevertheless insisted that 11,000 pounds of the fine should be paid at once, and, when the earl declared himself unable to find the money, his estates were seized, and funds were raised by granting leases on them. Northumberland did pay 11,000 pounds on 13 November 1613. He and his daughter had learnt an unforgettable lesson about royal power and nobles’ power.

Typically, Northumberland tried to recreate his private paradise inside the Tower. Thomas Harriot, once Walter Ralegh’s conjuror-servant, Walter Warner, and Thomas Hughes, the mathematicians, were regular attendants and pensioners, and were known as the earl’s ‘three magi’. And Northumberland had Walter Ralegh himself, also in the Tower, as an occasional companion. Nicholas Hill aided him in experiments in astrology and alchemy. A large library was placed in his cell, consisting mainly of Italian books on fortification, astrology and medicine; he also had Tasso, Machiavelli, Chapman’s Homer, The Gardener’s Labyrinth, Daniel’s History of England, and Florio’s Dictionary.

During her stay in the Tower, did Lucy read them? An intelligent girl might have been expected to do so. Another Lucy, Lucy Hutchinson, recalled her own intensive education:

By the time I was four years old, I read English perfectly, and having a great memory, I was carried to sermons, and while I was very young could remember and repeat them exactly … I had at one time eight tutors in several qualities, languages, music, dancing, writing and needlework; but my genius was quite averse from all but my book, and that I was so eager of, that my mother thinking it prejudiced my health, would moderate me in it. Yet this rather animated me than kept me back, and every moment I could steal from my play I would employ in any book I could find, when my own were locked up from me. After dinner and supper I still had an hour allowed me to play, and then I would steal into some hole or other to read. My father would have me learn latin, and I was so apt that I outstripped my brothers who were at school, although my father’s chaplain, that was my tutor, was a pitiful dull fellow.

Lucy Hay never became an eager reader, as Lucy Hutchinson did. Instead, she whiled away her time in exactly the way any adolescent girl would: she fell wildly in love with someone her father thought very unsuitable, the king’s Scottish favourite James Hay. But Lucy was also still a daughter in her father’s house. As dutiful daughters, Lucy and her elder sister Dorothy paid their father a visit in the Tower. In Lucy’s case duty was not rewarded. After he had given her sister a few embraces, Northumberland abruptly dismissed Dorothy, but instructed Lucy to stay where she was, asking her sister to send Lucy’s maids to her at once. ‘I am a Percy,’ he said, ‘and I cannot endure that my daughter should dance any Scottish jigs.’ The Percys who had been keeping the Scots out of England for several hundred years were speaking through him.

‘Come, let’s away to prison’, Northumberland might have said to his errant Cordelia, hoping that they would sing like birds in the cage. However, since he snatched Lucy away from an exceptionally lavish party put on just to impress her by her very passionate suitor, it seems unlikely that she was pleased. In any case, all her life, Lucy wanted anything but retirement. She wished to be at the centre of things. And her choice of partner was a sign of her lifelong brilliance at spotting just who was able to open secret doors to power.

To Northumberland, imprisoning his daughter along with him, and thus depriving the king’s favourite of his desires, might have seemed a nice and ironic revenge on the king who had unfairly locked him away. Revenge apart, however, Northumberland loathed James Hay. First, he was a Scot, and there was great resentment among English courtiers and nobles against those Scots brought south by James Stuart. Secondly, he was a favourite of the king who had just punished and shamed Northumberland. But more than all this, the antipathy seems to have been personal. On reflection it is hard to think of two more dissimilar men. Northumberland was intellectual, shy, proud, private, and above all of an ancient family. James Hay was a social being. If Northumberland loved books, James Hay loved banquets and parties.

Especially, he loved giving them. When he held a banquet, Whitehall hummed with servants carrying twenty or twenty-five dishes from the kitchens to the banqueting hall. It was James Hay who invented the so-called antefeast: ‘the manner of which was to have the board covered, at the first entrance of the guests, with dishes, as high as a tall man could well reach, and dearest viands sea or land could afford: and all this once seen, and having feasted the eyes of the invited, was in an manner thrown away, and fresh set on the same height, having only this advantage of the other, that it was hot’ Hay’s servants were always recognizable because they were so richly dressed. Or because they were carrying cloakbags full of uneaten food: ‘dried sweetmeats and comfets, valued to his lordship at more than 10 shillings the pound’. Once a hundred cooks worked for eight days to make a feast for his guests. The party he had put on to impress Lucy involved thirty cooks, twelve days’ preparation, seven score pheasants, twelve partridges, twelve salmon, and cost 2200 pounds in all. John Chamberlain thought it disgustingly wasteful, an apish imitation of the monstrous ways of the French. But it was exactly the ways of the French – elegance, taste, fashion – that made James Hay so personable, so modern. He also liked elegant clothes, court socials and courtly pursuits, especially tilting. He introduced Lucy to the pleasures of the court masque, a musical drama which combined the attractions of amateur theatricals, drawing-room musicmaking, and a costume ball. His wedding to Honora Denny had been accompanied by a masque by Thomas Campion, and in 1617, the year of his courtship of Lucy, he sponsored a masque subsequently known as the Essex House Masque. He also funded a performance of Ben Jonson’s Lovers Made Men.

Hardest, perhaps, for Northumberland to bear, Hay was the son of a gentleman-farmer of very modest means. He was on the make, charmingly and intelligently. He was no fool: he spoke French, Latin and Italian, and one of the reasons he liked to live at a slightly faster pace was that he had spent his youth in France learning about food, wine and pleasure. His choice of Lucy Percy as a bride was astute and sensible, too; he must have spotted her as a future beauty, and of course her family credentials were good, or would be when he had wheedled Northumberland out of gaol.

Lucy was abandoning her father’s world and its values in choosing James Hay. He must have fascinated her, enough to make her put up with virtual imprisonment to get her way, but it was not his looks that made him so appealing. Surviving portraits bear out Princess Elizabeth’s nickname for him, which was ‘camelface’. Encumbered with a notoriously shy and distant father, it may have been James’s easy charm that Lucy found irresistible. And she was only a teenager; though used to magnificence, she was not used to courtly sophistication. James exuded the suavity of French and Italian courts. He knew all about how things were done in those foreign places, then as now redolent with associations of class and chic. And coming from a difficult, even tempestuous marriage between two people of equal rank, she knew that nobility in a partner was no passport to married bliss. Most of all, and all her life, Lucy was alert to power – who had it, who did not, who was in, who out.

Finally, banquets and masques and feasts and court life offered Lucy a chance to take centre-stage. Northumberland was never going to offer her that. He thought great men’s wives existed ‘to bring up their children well in their long coat age, to tend their health and education, to obey their husbands … and to see that their women … keep the linen sweet’. Or so he wrote to his sons, at the very time when Lucy was incarcerated with him. He added that if wives complained, the best idea was to ‘let them talk, and you keep the power in your hands, that you may do as you list’.

Northumberland may have thought he had power, but as many men were to find when the Civil War began, the women in his family knew exactly where real influence lay. About this his daughter was wiser than he. Eventually she wore her father down. He began using pleas rather than force. He offered her 20,000 pounds if she publicly renounced James Hay. Lucy declined; she probably knew that he didn’t have the money, encumbered as he was by fines. Instead, she escaped from the Tower, and fled straight to James, who as Groom of the Stool was resident in the Wardrobe Building. Alas, he was in Scotland with the king, but he knew his Lucy. He left a fund of 2000 pounds for her entertainment while he was away.

James, on his return, worked sensibly on and through Lucy’s mother and sister, winning them with the same charm that had dazzled Lucy. Finally, in October 1617, the old earl gave in. He blessed the pair. Perhaps he was tired of seclusion in the Tower and knew Hay could procure his release. Perhaps Northumberland was forced to recognize what his daughter had noticed long before, that power had passed to a new and very different generation.

Lucy and James were married in November 1617. It was a quiet wedding by James’s usually ebullient standards, costing a mere £1600, but it was well attended: the king, Prince Charles, and George Villiers, later the powerful Duke of Buckingham, were among the guests. James Hay, in order, apparently, to overcome Northumberland’s prejudice against him, made every effort to obtain his release. In this he at length proved successful. In 1621 King James was induced to celebrate his birthday by setting Northumberland and other political prisoners at liberty. The earl showed some compunction in accepting a favour which he attributed to Hay’s agency.

James’s lightheartedness concealed a tragic past, however. His first wife, Honora Denny, was an intelligent and kind woman who had received dedications from Guillaume Du Bartas, one of John Milton’s role models. But she had died in 1614. Her death was the result of an attempted robbery; she had been returning from a supper party through the Ludgate Hill area when a man seized the jewel she wore around her neck and tried to run off with it, dragging her to the ground. Seven months pregnant, the fall meant she delivered her baby prematurely. She died a week later. Her assailant was hanged, even though Honora had pleaded that he be spared before her own death. It was a moment in which the two almost separate worlds of peerage and poor met violently; the meeting was fatal to both.

Despite this saintly act, Honora Denny Hay was no saint. Either James Hay’s taste in women was consistent, or his second wife modelled herself closely on his first. Honora Denny was a powerful figure because she was a close confidante of Anne of Denmark. Rumour said that she had used her position as the Queen’s friend to make sure a man who had tried to murder one of her lovers was fully punished. Lucy, the wilful teenage bride, was to become one of the most brilliant, beautiful and sought-after women in Caroline England, following her predecessor’s example studiously and intelligently. And if Honora Denny Hay had lovers, and got away with it, Lucy could learn from this too.

James Hay’s career was as glittering as she had predicted. Retaining his position as the king’s favourite without any of the slips that dogged the careers of Somerset and Buckingham, he did a good deal of diplomatic work which took him far from home. In 1619 he was in Germany, mediating between the emperor and the Bohemians, and paying a visit to William of Orange on the way home. William scandalized Hay by offering him a dinner in which only one suckling pig was on the table. On his next mission to France in 1621, James cheered himself by having his horse shod with silver; every time it cast a shoe there was a scramble for the discard. But it was not only the old-fashioned who might have preferred William’s solitary pig to James’s extravaganzas. The disapproval of courtly colleagues like Chamberlain symbolized the difficulty facing the Hays as they tried to get on in society.

This society was unimaginable to Anna Trapnel, as her world was to them. It was a milieu full of new and beautiful things, new ideas. The court was their world, headed by a king who came to own the greatest art collection in the history of England, while in Stepney people ate black bread and died daily in the shipyards that built trading vessels to bring his finds to England.

A Van Dyck portrait of Henrietta Maria with her dwarf Jeffrey Hudson painted in 1633 shows fragments, symbols of her court. The monkey is a representative of Henrietta Maria’s menagerie of dogs, monkeys and caged birds, while the orange tree alludes to her love of gardens. Van Dyck deliberately downplays regality; gone are the stiff robes and jewels of Tudor portraiture, and here is a warmer, more relaxed figure who enjoys her garden and pets and is kind to her servant.

Lapped in such care, the queen and Lucy were encapsulated in the jewel case of the royal household, which included everyone from aristocratic advisers and career administrators to grooms and scullions. At the outbreak of the war, it comprised as many as 1800 people. Some of these were given bed and board, others received what was called ‘bouge of court’, which included bread, ale, firewood and candles. The court also supported hordes of nobles, princes, ambassadors and other state visitors, who all resided in it with their households, such as Henrietta’s mother Marie de Medici, and her entourage.

The household above stairs was called the chamber (these were people who organized state visits and the reception of ambassadors); below stairs it was called simply the household (these were the people who did the actual work, the cooking, cleaning and laundering). Supporting the household accounted for more than 40% of royal expenditure. Many servants had grand titles, rather like civil service managers now: the Pages of the Scalding House, the Breadbearers of the Pantry. There were unimaginable numbers of them. The king had, for example, thirty-one falconers, thirty-five huntsmen, and four officers of bears, bulls and mastiffs. The queen had her own household, which included a full kitchen staff, a keeper of the sweet coffers, a laundress and a starcher, and a seamstress. There were over 180, not including the stables staff.

Charles’s court was divided into the king’s side and the queen’s side, horizontally. It was also very strictly divided vertically, with exceptionally formal protocols to enforce these divisions. Charles insisted on the enforcement of these protocols far more firmly than his father had. Only peers, bishops and Privy Councillors could tread on the carpet around the king’s table in the Presence Chamber, for example. All these labyrinthine rules had to be learnt and kept. The king’s chambers were themselves a kind of nest of Chinese boxes; the further in you were allowed, the more important you were. The most public room was the Presence Chamber; beyond it was the Privy Chamber, which could be entered only by nobles and councillors; beyond that was the Withdrawing Chamber and the Bedchamber, reserved for the king and his body servants, and governed by the Groom of the Stool.

Charles actively maintained seven palaces: Greenwich, Hampton Court, Nonesuch, Oatlands, Richmond, St James’s and Whitehall, and he also had Somerset House, Theobalds, Holdenby (in Northamptonshire), and Wimbledon, the newest, bought by Charles as a gift for Henrietta Maria in 1639. There were also five castles, including the Tower of London, and three hunting lodges, at Royston, Newmarket and Thetford (the last was sold in 1630). All were to be touched by the war. Many were ruined.

Whitehall was the king’s principal London residence, a status recognized by both the Council of State and Cromwell, who chose it as the principal residence themselves. It was a warren, a maze of long galleries that connected its disparate parts in a rough and ready fashion, and it was cut in two by the highway that ran from London to Westminster, and bridged (in a manner reminiscent of Oxford’s Bridge of Sighs) by the Holbein Gate. Set down in the middle of the medieval muddle, like a beautiful woman in a white frock, was the Inigo Jones Banqueting House: icy, classical perfection. The long, rambling corridors and rooms of Whitehall were full of tapestries, paintings, statues (over a hundred) and furniture; it illustrated the idea that a palace was about interiors and personnel, not architecture. In that, it was oddly like the houses Anna Trapnel knew.

But Charles and Henrietta tried to alter this muddle. Dedicated and knowledgeable collectors, they eagerly acquired and displayed beautiful art. St James’s had an Inigo Jones sculpture gallery in the grounds that had been built to house the astounding collection of the Duke of Mantua; a colonnaded gallery ran parallel to the orchard wall, whose roof was cantilevered over the gardens so the king could ride under cover if the weather was wet. Somerset House had belonged to Anne of Denmark, and now it became Henrietta Maria’s. There were thirteen sculptures dotted about its garden, some from the Gonzaga collection. In the chapel, some thirty-four paintings were inventoried during Parliament’s rule, some described in the angry terms of iconoclasm: ‘a pope in white satin’. (In a hilarious irony, this was where Oliver Cromwell’s body was displayed to the nation in 1658.) Hampton Court chapel had ‘popish and superstitious pictures’, later destroyed.

Among their other hobbies, Charles and Henrietta were eager gardeners – though neither picked up a spade. But they were both keenly interested in the visual and its symbolic possibilities. The garden, for the Renaissance, was not just an extra room, but an extra theatre, the setting for masques, balls and parties. But it was also a place to be alone and melancholy. It symbolized aristocratic ownership and control of the earth and its fruits. Like other visual arts, garden fashion was changing. As portraits became more realistic, gardens assumed a new and striking formality: mannerist gardens, with grottoes and water-works, gave way to the new French-style gardens, which were all about geometry and precision, and acres of gravel on which no plant dared spread unruly roots. André Mollet, a French designer whose ideas prefigured Le Nôtre’s Versailles, created gardens at St James’s and at Wimbledon House for Charles and Henrietta. It was not for nothing that this style became associated with the absolutism of the Bourbon kings, and Louis XIV in particular. Such baroque planting in masses seemed richly symbolic of the ordered world of obedient and grateful subjects beyond the garden gates. It symbolized their mastery over the realm; every little dianthus, in a row, identical, massed, smiling. No weeds.

But Charles and Henrietta were not just buyers of pictures and makers of gardens. They wanted to be great patrons, like the Medici. One of the first seriously talented artists that Charles managed to lure to England was Orazio Gentileschi, now best-known as the father of Caravaggio’s most brilliant follower, Artemisia Gentileschi. Orazio arrived in England in October 1626, perhaps as part of the entourage of Henrietta’s favourite Bassompierre. He came to England directly from the court of Marie de Medici. Orazio was so much Henrietta’s painter that he was buried beneath the floor of her chapel at Somerset House when he died, an entitlement extended to all the queen’s Catholic servants. She may have liked him because, like her beloved husband, he always wore the sober, elegant black of the melancholy intellectual. He was also small and slight, like Charles.

His greatest commission was probably Henrietta’s own idea; nine huge panels for the ceiling of the Queen’s House at Greenwich. Greenwich itself, referred to as ‘some curious device of Inigo Jones’s’, was also called ‘the House of Delight’. The house was elegant, smooth, very feminine – seventeenth-century minimalism, but with curves, with grace. The paintings added colour and fire. The white-and-gold ceiling was augmented with the brilliant colours of a sequence that was to be called Allegory of Peace and the Arts under an English Crown. The so-called tulip staircase is a misnomer, but a felicitous one, since it conveys the long elegant lines of the curling flights. And like the tulip craze, the palace’s glory was short-lived, for its mistress did not enjoy it for long. Its post-war fate was to become a prison for Dutch seamen, a victim of Parliament’s iconoclasm.

In the seventeenth century, artists often worked with family members; in acquiring Orazio’s services, Charles and Henrietta also gained those of his brilliant daughter. Artemisia almost certainly helped her father with the sequence, while the plague raged through London and the armies gathered reluctantly for the Bishops’ Wars. Orazio’s two sons played a crucial role in Charles’s activities as a collector, going to the Continent to advise King’s Musician Nicholas Lanier when he was negotiating to buy the Duke of Mantua’s collection, the biggest single picture purchase by an English sovereign. Lanier also bought Caravaggio’s astounding and magnificent Death of the Virgin for Charles secretly in Venice. And the melancholy, artistic Richard Symonds suggests a closer relationship between these two exceptionally talented royal servants; in describing Lanier, Symonds calls him ‘inamorato di Artemisia Gentileschi: che pingera bene’ (lover of Artemisia Gentileschi, that good painter) while Theodore Turquet de Megerne says Nicholas Lanier knew artistic techniques that were Gentileschi family secrets; they could have met in Rome or Venice, via Artemisia’s brothers. If so, this was an affair between two of the most talented people at Charles and Henrietta’s court. However the country felt about them, the king and queen had created a world in which such talent could flourish, and find an echo in the mind of another.

And the royal couple could be influenced by this cultural world of their own making. Artemisia says something in one of her letters that is very reminiscent of remarks Henrietta makes about herself during the war: ‘You will find that I have the soul of Caesar in a woman’s heart’ (13 November 1649). Henrietta was to call herself a she-generalissima in similar fashion.

Other schemes came to nothing. Henrietta had ordered a Bacchus and Ariadne from one of her favourite artists, Guido Reni of Bologna, whose Labours of Hercules was one of the paintings Charles had acquired from the Duke of Mantua. It was never sent to London because Cardinal Barberini thought it too lascivious. A cut-price deal was done to ornament the withdrawing room with twenty-two paintings by Jacob Jordaens, a pupil of Rubens, bound to charge much less than the master himself. Balthasar Gerbier tried to get the job for Rubens, promising that the master would not seek to represent drunken-headed imaginary gods, but that he was ‘the gentlest in his representations’. Nonetheless, the royal couple chose the cheaper pupil, with instructions not to tell Jordaens who the clients were, in case he raised his price. He was also firmly told to make his women ‘as beautiful as may be, the figures gracious and svelte’. Gerbier kept on pushing to get the commission for Rubens, but on 23 May, he had to report the failure of his hopes with Rubens’ death. Eight of Jordaens’s paintings were duly executed; like many another artist in the service of Charles and Henrietta, he saw only a small portion of his promised fee, £100 of £680.

The might of the court, its self-absorption and glory, is best glimpsed in the way it displayed its own world to itself. The court masque was like a mirror, gleaming, shining. It was also like an insanely elaborate production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at a well-endowed school; big sets, but amateur actors.

Shrovetide 1630 was a festivity from the seventh Sunday before Easter till the following Tuesday (now called Shrove or Pancake Tuesday). The idea was to eat up all the meat, eggs, cheese and other foods forbidden in Lent. But Shrove also meant shriving or confession of sins, and the gift of absolution from them. The godly didn’t like it much; it was ‘a day of great gluttony, surfeiting and drunkenness’, thought one godly minister, and it was also a day for football and cockfights. In choosing it for her first big masque, called Chloridia, and telling the story depicted in Botticelli’s Primavera, Henrietta was trying to tame festivity, to make it her own, and to combine fun with the shriving of sin, with redemption. The masque’s preface recorded the splendour of the event:

The celebration of some Rites, done to the Goddess Chloris, who in a general counsel of the Gods, was proclaimed Goddess of the flowers, according to that of Ovid, in the Fasti. The Curtain being drawn up, the Scene is discovered, consisting of pleasant hills, planted with young trees, and all the lower banks adorned with flowers. And from some hollow parts of those Hills, Fountains come gliding down, which, in the far-off Landshape, seemed all to be converted to a River. Over all, a serene sky, with transparent cloudes, giving a great lustre to the whole work, which did imitate the pleasant Spring. When the spectators had enough fed their eyes, with the delights of the Scene, in a part of the air, a bright Cloud begins to break forth; and in it is sitting a plump Boy, in a changeable garment, richly adorned, representing the mild Zephyrus. On the other side of the Scene, in a purplish Cloud, appeareth the Spring, a beautiful Maid, her upper garment green, under it, a white robe wrought with flowers.

The resemblance to a mythological painting by an Italian or Flemish master is clear. Inigo Jones, the creator of its visual aspects, carefully borrowed books about continental wedding pageants from the Cotton library. He suggested a costume for Henrietta herself, ‘several fresh greens mixed with gold and silver will be most proper’. This was Ben Jonson’s last court masque, and he made the most of it. Attendance was by invitation, and those not among the called and chosen had little hope of getting in; boxes were overflowing with richly dressed ladies as it was. They wore shockingly low-cut dresses, too, thought the Venetian embassy chaplain: ‘those who are plump and buxom show their bosoms very openly, and the lean go muffled to the throat’. There were feathers, and jewels, and brightly coloured dresses. One of the scantily-clad dancers was Lucy Hay. The masque began at about 6 p.m., and afterwards the king attended a special buffet supper for the cast. At the end of the evening the supper table would be ceremoniously overthrown amidst the sound of breaking glass, so dear to the upper classes, as a kind of violent variant of James Hay’s double feasts.

Charles and Henrietta were good at the visual, and they also had in Nicholas Lanier a fine musician. Their pet poets were less distinguished. Here is William Davenant: ‘How had you walked in mists of sea-coal smoke,/ Such as your ever-teeming wives would choke/ (False sons of thrift!) did not her beauteous light/ Dispel your clouds and quicken your dull sight?’

Shakespeare it isn’t, but it is fascinating testimony to the returning traveller’s first impression of London; coal fires – whoever you were. Coal, and its black dust, linked Henrietta and Lucy to Anna Trapnel’s Stepney.

And Lucy Hay, too, had to instruct her maids to get the coal dust off the new upholstery. The first years of Lucy’s marriage were difficult. She fell ill, so seriously that she nearly died, and perhaps as a result of this illness, she suffered the tragic stillbirth of the only baby she would ever carry. Having married a man with no money of his own, dependent on the king for favours, Lucy was in an oddly vulnerable position. She and her husband needed her efforts to survive James I’s death in 1625 without loss of position. And they had a tremendous stroke of luck early in the new reign. Exasperated with Henrietta Maria’s French ladies-in-waiting, Charles literally threw them out on 7 August 1626. James Hay may have been among those who urged this; Buckingham certainly was. The list of replacements included Lucy. But Henrietta didn’t want her – hers was the name which made the young queen balk.

It is easy to understand the queen’s difficulties. Henrietta was young, and rather daunted by England and the English court. Lucy was beautiful and clever and seems to have struck every man who met her as a kind of goddess. What queen consort in her senses would want her footsteps dogged day and night by somebody so very desirable, so charismatic? Henrietta wanted to lead; she didn’t want to follow. And Lucy’s sexual reputation had begun its nosedive. It was widely assumed that she was the mistress of that most glittering, most hated upstart of all, the Duke of Buckingham, and that Hay and Buckingham both hoped to use her to gain power over the young queen. Henrietta was quite intelligent enough to resent this. And she hated Buckingham, and detested his power over her husband.

Her mixed feelings about Lucy might have had another, darker cause. It may be that James Hay and Buckingham were both hoping that Charles might become infatuated with Lucy, that they might be able to control the king through his mistresses. This was not a stupid idea: the strategy was to pay rich dividends with Charles’s son, after all. And even the rumour cannot have endeared Lucy to the young, insecure queen, who believed passionately in marital fidelity.

And how might Lucy have felt about these plans? The self-willed girl, who chose her own husband? Perhaps the sense of being used and ordered in and out of bed bred a curious solidarity between Lucy and the queen, since in these unpromising circumstances Lucy somehow triumphed. By the summer of 1628, she had become Henrietta’s best friend and closest lady-in-waiting. As James Hay had taught her, she used dinners and entertainments: Bassompierre, the French ambassador, reported on Lucy’s cosy supper parties ‘in extreme privacy, rarely used in England, and caused a great stir, since the Queen rarely associates with her subjects at small supper gatherings’. This was high fashion, exciting, vivid, very faintly transgressive. It was women-only, too. Bassompierre noted that the king ‘once found himself in these little festivities … but behaved with a gravity which spoiled the conversation, because his humour is not inclined to this sort of debauche’. The kind of games which may have been played are exemplified by Lucy’s doglike and ambitious follower Sir Tobie Mathew, who wrote a character of her; it can be read as nauseatingly fulsome or very double-tongued indeed. Those who saw it as flattery agreed that it was ‘a ridiculous piece’. In his character, Mathew praises her ability to turn aside her followers’ wooing by seeming not to understand them. What Lucy liked was the idea of love, love as a game: a solemn Platonic game, yes, but one that could at any moment be deflated by sharp satire.

It was typical of Lucy that she could bring triumph even out of the disaster of serious and disfiguring illness. When she developed smallpox in the hot summer of 1628, it coincided very neatly with the death of the Duke of Buckingham, who had come to be James Hay’s rival and enemy. Buckingham’s death left an enormous gap at the very centre of power, a gap which James and Lucy Hay raced to fill. Everyone wrote to James, who was in Venice, urging him to return to England at once, even urging Lucy’s illness as a good excuse. In fact, though, James was both too late and not needed. The person who stepped into Buckingham’s position of power and influence over Charles was in fact his queen, Henrietta. And Lucy had assiduously cultivated her. Henrietta loved Lucy so much that she could hardly be restrained from nursing her personally. When Lucy began to recover, Henrietta rushed to her side.

But despite these glowing moments, the relationship had its ups and downs. Tobie Mathew could report in March 1630 that Lucy and Henrietta were not as close as before, and by November William, Lord Powys could inform Henry Vane that Lucy was back in full favour again. The problem sometimes seemed to be that Lucy was not very good at being a courtier: her natural dominance sometimes overpowered her political instincts. Powys remarked that ‘she is become a pretty diligent waiter, but how long the humour will last in that course I know not’. And although she and Henrietta had much in common, they were very different in inclination and temperament. Lucy’s rather Jacobean liking for fun, frivolity and parties was not altogether shared by Henrietta, who liked her parties too, but preferred them to have serious moral themes. When another of Henrietta’s advisers lamented that the wicked Lucy was teaching the queen to use makeup, he was complaining that she brought some Jacobean dissoluteness to the primness of the new court. Henrietta had moods in which she found this fun, and moods in which it made her feel shamed and guilty, particularly since Lucy could not share the great passion of her life, her Roman Catholic religious zeal. Finally, as Tobie Mathew remarked, Lucy was really a man’s woman: ‘She more willingly allows of the conversation of men, than of Women; yet, when she is amongst those of her own sex, her discourse is of Fashions and Dressings, which she hath ever so perfect upon herself, as she likewise teaches it by seeing her.’