По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

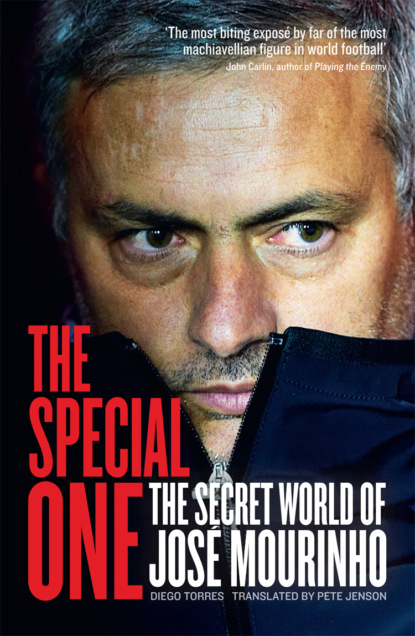

The Special One: The Dark Side of Jose Mourinho

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Pérez’s communications advisors understood from the outset that he set great store in the concept of fantasy. Ilusión and the spectacular are connected concepts. The dictionary defines the word ‘spectacular’ as an adjective applied to things that, because of the ‘apparatus’ that accompanies them, impress whosoever is in their presence. The meaning can even be extended to imply ‘gimmicky’. The first definition of ‘ilusión’ in the Royal Academy’s Dictionary of the Spanish Language is emphatic: ‘concept, image or representation without an actual reality, suggested by the imagination or caused by a delusion of the senses’.

José Luis Nueno, professor of commercial management at the IESE (Institute of Higher Business Studies) and author of a study of Madrid’s business model for Harvard Business School in 2004, questioned the logic of the choice of Mourinho and considered that in a traditional enterprise his signing would at the very least be seen as unorthodox. It would be an error, says Nueno, ‘for a company to imitate another in terms of who its leader is: to believe that one person is responsible for everything is like believing that the carrying out of one task is responsible for everything. It’s like saying: if I buy the shop-window displays of Zara I am Zara. Or even, if I copy everything that Zara does I am Zara. You miss the relationships between all the bits and pieces in the system. And you lose the acquired experience of developing that system.’

Traditional industry is less sensitive to the mythology that fills the minds of football fans. Inter’s defeat of Bayern to win the Champions League gave Mourinho another trophy, but, more importantly, it gave him a magical glow in the eyes of many Madrid supporters and the feeling that they had finally found their essential authoritarian patriarch for these difficult times. Somebody who could part the Red Sea. Is there anything more exciting, more full of ilusión, than beautiful superstition?

Nobody knew how to exploit this better than Mourinho, ever more conscious of the fact that his collection of trophies gave him an incalculable capacity to influence the minds of fans and directors: two Portuguese leagues, two English leagues, two Italian leagues, a Portuguese Cup, an English Cup, an Italian Cup, a UEFA Cup, two Champions Leagues … Success is exciting. Continual success, skilfully promoted, is persuasion’s most seductive calling card. It is then that ‘magical thinking’ comes in to play.

In The Golden Bough, the anthropological classic published in 1890, James Frazer writes that primitive societies linked themselves to a ‘magical man-god’ who exercised ‘public magic’, primarily to provide food and control the rain. We don’t expect anything less from the director generals who control the big multinationals, nor of certain football managers. Frazer argues that magic works by imitation: what appears to be, influences what appears to be. Like causes like. If you want more muscle, eat more meat; if you want to fly, eat birds; if you want success, attach yourself to someone successful, touch him, ask for his autograph. Magic works through symbols and symbols work by metonymy and metaphor – Mourinho is a symbol of the social leader and a metaphor for triumph.

Magical thinking establishes a mystical relationship that very few people in the world of football are capable of resisting, as nobody is wholly free from superstition. Players can’t stop themselves, always taking their first step onto the pitch with their right foot. Roman Abramovich cannot suppress it, trying to import the Guardiola model to Chelsea, but without the ‘Masia’, without the culture of youth development, without the Camp Nou, and to an environment completely different to that of Spanish football. Neither could Pérez restrain himself when he coupled his desire to win the Champions League to a coach who had won it twice.

Champions League statistics brought Mourinho closer to Madrid. But those same numbers made it mathematically less likely that he would win it again. Bob Paisley is the only coach to have won three European Cups, and he did it from within a very stable club: the Liverpool of the seventies and eighties, a club that had been built on the firm foundations laid by Bill Shankly with a continuity that went back to 1959.

Mourinho himself must have noted a degree of rage from within the club when two months after arriving in Spain, after an unexpected 0–0 draw on his league debut in Mallorca, he felt obliged to clarify that he was not a magician.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘I’m a coach. I’m not Harry Potter. He’s magic but in reality magic doesn’t exist. Magic is fiction and I live in the football world, which is the real world.’

Mourinho wanted to lower the levels of expectation. But he always knew that his signing was intimately related to marketing, a science that studies how to take advantage of expectations for economic ends. Harry Potter is not just a fictional character. He is a commercial system learned in the business schools well known to José Ángel Sánchez. When Madrid signed the Brazilian forward Ronaldo in 2002 the director general compared his impact on the economy of the club to the bespectacled boy wizard, saying that ‘Ronaldo is Harry Potter’.

The commercial model of the Madrid brand that Sánchez inspired when he joined the club is the same that Disney used to promote The Lion King. Following a sequence outlined by the concept’s inventor, Professor Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist and a specialist in the economics of information, Disney developed an exploitation chain that multiplied the number of times a product could be offered to the public. The way a product was presented was expected to evolve, generating new expectations and new demand. Varian called these ‘windows’. The first window of a film is at the cinema. The second is the showing of the film on passenger airlines; then, the release of the DVD; next, the barrage of articles with the image of the characters on patented toys, games, electronics, textiles, furniture, etc. And finally, the musical, or any other commodity that the imagination is capable of conceiving.

‘Disney is a content producer, and we’re another content producer,’ Sánchez explained during the galáticos era, as he maximised profits from Figo, Zidane, Ronaldo and Beckham as if they were characters in a cartoon series. The director general glimpsed a universe in which supporters were transformed into ‘audiences’ and became consumers of legend. During a game, these excited customers could be divided into three blocks, according to how they consumed the product. In the stadium are those who have paid at the turnstiles; the people who have bought a private box, the companies that hire out their boxes; or private individuals who have hired VIP areas, everyone in their consumer ‘window’. In the second block outside the stadium are companies paying broadcasting rights for live and subsequent transmission on TV and the internet.

But the spectacle does not finish at the end of the game: the club’s in-house media, Real Madrid TV, the official web page and the various club shops go on drawing in a third wave of customers. In this last block are the sponsors. The players lend their image for the promotion of companies who have contracts with the club, such as Audi, Telefónica, Coca-Cola, adidas, Babybel, Nivea, Samsung, Bwin and Fly Emirates. And then comes the film, a climax promising to break through the final frontier. Real: The Movie, released in 2005, was the ultimate example of putting Varian’s theory into practice. At this point Real Madrid were more like Disney than Disney could ever be like Real Madrid.

More than creating new icons capable of raising the market value of the product, from 2000 Sánchez and Pérez were looking for people who were already famous, established celebrities prepared to incorporate their own mythology into the club. Before signing for Paris Saint-Germain, a Brazilian international was offered to the club, his name Ronaldinho Gaúcho. A high-ranking Madrid official, however, dismissed the idea after passing judgement on the player’s prominent teeth. Ronaldinho was – within Disney parameters – an absolute unknown and the casting was not being done by a football expert. As a result, David Beckham was the only signing of the 2003–04 season. The Englishman possessed an image that had, in the words of the president, ‘universal projection’.

Along with the sale of the land on the Avenida Castellana to build skyscrapers where the old training ground had stood – a real-estate operation that transformed Madrid’s horizons dramatically – Sánchez and Pérez’s formula helped the club make a great deal of money. In the financial year ending in 2005 Madrid became the highest-grossing club in the world. The sum of €276 million entered the Bernabéu coffers, €30 million more than that earned by Manchester United, until this point the world’s most financially powerful club. Negotiation of TV rights in 2006 concluded with an unequal distribution of funds, to the detriment of all first and second division clubs apart from Barcelona and Madrid, who were blessed with the biggest contracts in Europe.

Not even when the economic bubble burst did the club’s income stop growing. At the end of the 2011–12 season it exceeded €500 million, and Pérez was also able to show off a league title, his first as president since 2003. It was the first and last Spanish league won by Mourinho.

Chapter 3

Market (#uf262fc09-2ee0-5f85-99b0-0ea07150a3f7)

‘You are Peter, the rock on which I will build my church, and the gates of Hell will not prevail against her. To you I give the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven; and what you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.’

Matthew, 16:18–19

‘The foundations of this our city are as firm as the convictions of all who love Real Madrid. An institution that respects its past, learns from its present and is firmly committed to its future.’

Inscription on the foundation stone at Valdebebas

Football nights at the Ciutat de València stadium have a distinctive feel. The salty sea air, the smell of sunflower seeds from the stands, the penetrating aroma of liniment on the ceramic-tile floors of the dressing rooms, boots scattered on the ground, incandescent lamps giving off slightly less light in the visitors’ dressing room than in the home one, the kind of lamps you find in hospital rooms, lighting up the face of Pedro León as he gets changed, reasonably satisfied after the game on 25 September 2010.

The crowd had just applauded him off the pitch in recognition of the time he spent at Levante three seasons ago. He had been Madrid’s best player and had done what his coach had asked, or so he thought.

Mourinho had brought him on after 61 minutes in place of Di María in an attempt to break down Levante’s defence. He told him to hug the touchline, to open up the pitch, to take people on and try to get around the outside of the opposition’s defence; and if there was space to do so, to make diagonal runs inside, combining with Benzema and Higuaín. The substitute carried out his coach’s instructions although from the bench he was being stared at by a clearly annoyed Mourinho. Furious, he grabbed a bottle of water and threw it to the ground. Despite the fact that he had created a chance for himself and served up another simple opportunity for Benzema to score, the match ended 0–0.

Pedro León was preparing to go to the bus when Mourinho stopped him in the dressing room and, calling the attention of the other players, pointed the finger of blame at the hapless Spaniard.

‘I’ve heard you’re going around like a star, saying you have to be starting games and doing whatever the hell you like. Your friends in the press, that Santiago Segurola … they say you’re a star. But what you’ve got to learn is to train hard and to not go around saying you have to be a starter. You’re going to be left out of the squad for several games. On Monday you won’t be going to Auxerre …’

‘I didn’t say that,’ the accused responded, stunned. ‘Tell me. Who have I told that I should be starting? We should talk in private. Please, boss, let’s talk in private …’

Mourinho sneered before turning around. The dressing room was electrified. The players did not understand what had happened to suddenly make the coach ruthlessly belittle someone who seemed so vulnerable. A 23-year-old newcomer to the team. A talented footballer who the group saw as a solution to the creative problems the team sometimes faced in away games. A player who had just shown against Levante that he was up to the task had been accused by the manager of being a kind of traitor, based on some idle gossip that it seemed only Mourinho had heard.

On Monday 27 September Madrid travelled to the French city of Auxerre to play their second group game in the Champions League. The absence of Pedro León caught the attention of both directors and journalists. That evening, during the official press conference, someone asked Mourinho the technical reasons behind his decision not to call up one of the players who had most impressed in the previous match. The question was either to be evaded or invited a football-based refection, but the answer Mourinho gave suggested the most powerful man at the club was almost out of control.

‘Speculation is your profession,’ he told reporters in a steely, inflexible tone that was then new but which, over time, would become almost routine. ‘In very pragmatic terms I could say that Pedro León has not been called up because the coach didn’t want to call him up. If President Florentino comes to ask me why Pedro León hasn’t been called up I have to answer him. But he’s not asked me. You’re talking about Pedro León as if he’s Zidane or Maradona. Pedro León is an excellent player but not so long ago he was playing for Getafe. He’s not been called up for one game and it feels like you’re talking about Zidane, Maradona or Di Stéfano.

‘You’re talking about Pedro León. You have to work to play. If you work as I want you to, then it will be easier to play. If not, it will be more difficult.’

Mourinho spoke with a mixture of cruelty and pleasure. The sadistic nature of the rant unsettled the squad. It was the first time that the players felt their manager represented a threat. Gradually, they began to follow his every public appearance: on TV, on the web, via Twitter, with iPhones or BlackBerries. They didn’t miss a single appearance because they understood that in the press room a different game was being played out, one that would have a major effect on them professionally; a game that could ennoble or degrade them, place them in the spotlight or bury them with indifference, conceal their misery or entirely disregard their merits – a ritual of four weekly appearances that they only had access to as spectators.

Real Madrid’s statute book establishes the board as the executive body of government responsible for directing the administration of the club. In practice, it works as a small, homogeneous parliament that meets regularly to discuss issues proposed by the president for approval. With the exception of the group closest to the president, whose position enables direct channels of inquiry, the confidential information handled by board members is usually limited to sources in the offices of the Bernabéu, offices well removed from the football team. Because directors are hand-picked by the president, Florentino Pérez, he has never met with overwhelming opposition and, except on rare occasions, the board unanimously agrees.

José Manuel Otero Ballasts, recognised by Best Lawyers magazine as the top intellectual property lawyer in Spain, is Professor of Law at the University of Alcalá de Henares, a former dean of the Faculty of Law of the University of León, author of detective novels and one of the 17 members of the board of directors. Asked in November 2010 about the character of José Mourinho, this most intellectual of Madrid’s directors turned to the Bible for reference:

‘When Jesus named the man who was to lead his Church he did not choose the even-tempered calm John, but Peter, the passionate, hot-blooded fisherman. Mourinho plans everything, everything, everything … his intelligence enables him to analyse the reality of a situation and project his own solutions. I had never before heard Casillas say that a coach had been “great” during half-time [the goalkeeper said this to the media after the victory in Alicante in October 2010]. They all adore him. He’s a communicator. He encloses the players verbally. He’s been successful in all the signings. It’s the first time I’ve seen this level of calm at the club.’

José Ángel Sánchez, the corporate director general, offered an equally complimentary account of Mourinho:

‘The coach,’ said Sánchez, ‘is like Kant. When Immanuel Kant went out for his walk in Königsberg everyone set their watches because he always did it on time. When the coach arrives in the morning at Valdebebas everyone knows that it’s 7.30 a.m. without looking at the clock.’

Sánchez felt that Madrid had its first coach who could be trusted to sign wisely. He cited the example of Khedira and Di María, whom the coach – showing what a clinical eye he had – asked for before the 2010 World Cup. He argued that his compendium of virtues made him exactly the solid figure that the club had needed for so many years. Mourinho, in the opinion of the chief executive, had ‘brought calm’ to Madrid.

The sports complex Valdebebas, known as Real Madrid City, is one of the most advanced centres of football technology in the world. It occupies an area of 1.2 million square metres, of which only a quarter has been developed, at a cost of some €98 million. The work of the architectural studio of Antonio Lamela, it has 12 playing fields, a stadium and, at its heart, a ‘T-shape’ of standardised units whose functionalist design of flat layers and clean lines projects a mysteriously moral message.

The main entrance, at the foot of the ‘T’, is at the lowest point of the facility. From there the complex unfolds, beginning with the dressing rooms of the youngest age categories (8- to 9-year-olds) and going through, in accordance with age group, the dressing rooms of each category, using the natural slope of the hill on the south side of the valley of Jarama. The architects, in collaboration with the then director of the academy, Alberto Giráldez, gave the main building an educational message for young people: the idea of an arduous climb from the dressing rooms of the youngest to those of the professionals. On top of this great parable of conquest – and indeed of the whole production – sits the first-team dressing room. And above the dressing room, with the best views of all, sits the coach’s office, defining its occupier as the highest possible authority. As Vicente del Bosque said of his predecessor as head of the academy, Luis Molowny: ‘He was a moral leader.’

Something in Mourinho’s arrival at Valdebebas surprised those who worked there. As well as Rui Faria, fitness coach, Silvino Louro, the goalkeeping coach, Aitor Karanka, the assistant coach, and José Morais, the analyst of the opposition, the Portuguese coach brought his agent and friend, Jorge Mendes. Gradually, the squad became convinced that Mendes worked in the building. Not so much as another one of the coaches but as the ultimate handyman.

Impeccably fitted out in a light woollen Italian suit, with a tie that never moved and a fashionable but unpretentious haircut, tanned even in the gloomiest of winter days, Jorge Paulo Agostinho Mendes was the first players’ agent who saw himself as a powerful businessman, often speaking as a self-styled agent of the ‘industry’ of football. Mourinho also used the term ‘industry’ in his speeches, seasoning his turns of phrase with expressions from the world of financial technocracy. For many other football agents, this was an artificial pose. ‘They think they’re executives at Standard & Poor’s,’ said one Madrid player’s FIFA agent.

Born in Lisbon in 1966, Mendes was raised in a working-class neighbourhood. His father worked in the oil company Galp and he won his first trophies selling straw hats on the beach in Costa Caparica. He played football at junior championship level and, determined to make it as a professional, migrated north to Viana do Castelo. He ran a video rental store, worked as a DJ and opened his own nightclub in Caminha, before discovering that he had a gift – the talent of first being able to gain the trust of players, and then being able to value them, generally above market prices. His first major transaction was the transfer of goalkeeper Nuno from Vitória de Gimarães to Deportivo de la Coruña in 1996. With the commission obtained from the deal, the foundation was laid for Gestifute to become the football industry’s most powerful agency, with subsidiaries such as Polaris Sports, dedicated to the management of image rights, marketing and advertising, and the promotional agency Gestifute Media.

Mourinho and Mendes shared an office straight away. The agent set himself up in the suburb of La Finca in Pozuelo. He went to Valdebebas, along with his players and his coach, almost every morning, accompanied by various assistants. When it was training time he would sit in Mourinho’s chair and look out of the window from his own private agency to follow the progress of the team from up on high.

The sight of Mendes in his dark-blue pinstripe suit sitting behind the glass, drinking coffee and looking at everything from behind the mask of his sunglasses, sparked the imagination of the players every morning as they warmed up. There was no shortage of jokes and laughter. Especially when jogging as a group, they had the feeling they were being watched from above.

‘There’s the lord and master of the club,’ said one. ‘There’s the boss.’

Mendes entertained his business partners in Mourinho’s office. There they organised their interviews with other agents. Juanma López, the former Atlético player, who was now a players’ agent, appeared one morning. It was a topic of conversation for the naturally curious players. ‘Mendes has his office here,’ they commented. Lass Diarra did not understand what all the fuss was about: ‘Who’s that?’ he said. The Frenchman had never seen López play.

The first stone of Valdebebas was laid on 12 May 2004. During the opening Pérez gave a visionary speech: he imagined a huge theme park that club members could access daily and in which they rubbed shoulders with the players.

‘The new “City of Real Madrid” has an inclusive character,’ he said. ‘It will be open to all who love the sport and want to enjoy all the possibilities for entertainment around it.’