По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

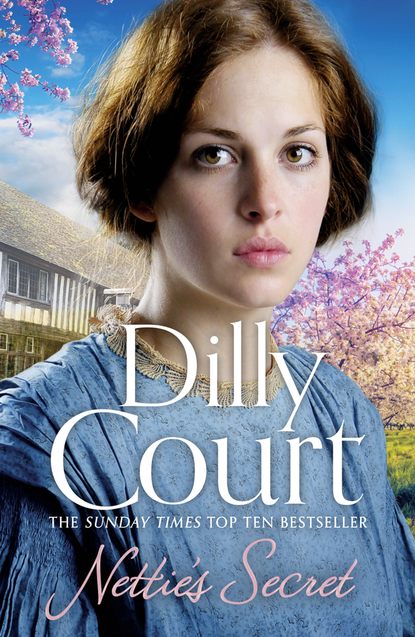

Nettie’s Secret

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Dilly Court

About the Publisher

Chapter One (#u927bd60e-443d-5d9c-b74f-fa197a2d0d32)

Covent Garden, 1875

Robert Carroll appeared in the doorway of his attic studio, wiping his hands on his already paint-stained smock. A streak of Rose Madder appeared like a livid gash on his forehead. ‘Nettie, I want you to go to Winsor and Newton in Rathbone Place and get me some more Cobalt Blue, Indian Yellow and Zinc White. I can’t finish this painting without them.’

Nettie looked up from the garment she had been mending. ‘Do you need them urgently, Pa? I promised to finish this for Madame Fabron. It’s the opening night of her play at the Adelphi, and she must have her gown.’

‘And I have to finish this commission, or I won’t get paid and we’ll find ourselves homeless. We’re already behind with the rent, and Ma Burton isn’t the most reasonable of souls.’

‘All right, Pa. I’ll go, but I thought we didn’t have any money, which was why we had nothing but onions for supper last night.’ Reluctantly, Nettie laid her sewing aside.

‘Food is not important when art is concerned, Nettie,’ Robert said severely. ‘I can’t finish my work without paint, and if I don’t get this canvas to Dexter by tomorrow there’ll be trouble.’ He took some coins from his pocket and pressed them into her hand. ‘Go now, and hurry.’

‘I know you think the world of Duke Dexter, but how do you know that the copies you make of old masters’ works aren’t passed off as the real thing?’ Nettie pocketed the money. ‘You only have Duke’s word for the fact that he sells your canvases as reproductions.’

‘Nonsense, Nettie. Duke is a respectable art dealer with a gallery in Paris as well as in London.’ Robert ran his hand through his hair, leaving it more untidy than ever. ‘And even if he weren’t an honest dealer, what would you have me do? Commissions don’t come my way often enough to support us, even in this rat-infested attic.’

‘I still think you ought to check up on him, Pa.’

‘Stop preaching at me, Nettie. Be a good girl and get the paint or we’ll both starve to death.’

‘You have such talent, Pa,’ Nettie said sadly. ‘It’s a pity to squander it by making copies of other people’s work.’ She snatched up her bonnet and shawl and left her father to get on as best he could until she returned with the urgently needed paints. Everything was always done in a panic, and their way of living had been one of extremes ever since she could remember. When Robert Carroll sold one of his canvases they lived well and, despite Nettie’s attempts to save something for the lean times to come, her father had a habit of spending freely without any thought to the future.

Nettie made her way down the narrow, twisting staircase to the second floor, where the two rooms were shared by the friends who had kept her spirits up during the worst of hard times. Byron Horton, whom she thought of as a much-loved big brother, was employed as a clerk by a firm in Lincoln’s Inn. Nettie had been tempted to tell him that she suspected Marmaduke Dexter of being a fraud, but that might incriminate her father and so she had kept her worries to herself. The other two young men were Philip Ransome, known fondly as Pip, who worked in the same law office as Byron, and Ted Jones, whose tender heart had been broken so many times by his choice of lady friend that it had become a standing joke. Ted worked for the Midland Railway Company, and was currently suffering from yet another potentially disastrous romantic entanglement.

Nettie hurried down the stairs, past the rooms where the family of actors resided when they were in town, as was now the case. Madame Fabron had a small part in the play Notre-Dame, or The Gypsy Girl of Paris, at the Adelphi Theatre, with Monsieur Fabron in a walk-on role, and their daughter, Amelie, was understudy to the leading lady, Teresa Furtado, who was playing Esmeralda. The Fabrons were of French origin, but they had been born and bred in Poplar. They adopted strong French accents whenever they left the building in the same way that others put on their overcoats, but this affectation obviously went well in the theatrical world as they were rarely out of work. Fortunately for Nettie, neither Madame nor her daughter could sew, and Nettie was kept busy mending the garments they wore on and off stage.

She continued down the stairs to the ground floor, where sickly Josephine Lorimer lived with her husband, a journalist, who was more often away from home than he was resident, and a young maidservant, Biddy, a child plucked from an orphanage. Nettie quickened her pace, not wanting to get caught by Biddy, who invariably asked for help with one thing or another, and was obviously at her wits’ end when trying to cope with her ailing mistress. Not that she had many wits in the first place, according to Robert Carroll, who said she was a simpleton. Nettie knew this to be untrue, but today she was in a hurry and she was desperate to avoid their landlady, Ma Burton, who inhabited the basement like a huge spider clad in black bombazine, waiting for her prey to wander into her web. Ma Burton was a skinflint, who knew how to squeeze the last penny out of any situation, and her cronies were shadowy figures who came and went in the hours of darkness. Added to that, Ma Burton’s sons were rumoured to be vicious bare-knuckle fighters, who brought terror to the streets of Seven Dials and beyond. It was well known that they were up for hire by any gang willing to pay for their services. It was best not to upset Ma and incur the wrath of her infamous offspring and their equally brutal friends.

Nettie escaped from the house overlooking the piazza of Covent Garden and St Paul’s, the actors’ church, and was momentarily dazzled by the sunshine reflecting off the wet cobblestones. She had missed a heavy April shower, and she had to sidestep a large puddle as she made her way down Southampton Street. It would have been quicker to cut through Seven Dials, but that was a rough area, even in daytime; after dark no one in their right mind would venture into the narrow alleys and courts that radiated off the seventeenth-century sundial, not even the police. Nettie stopped to count the coins her father had given her and decided there was enough for her bus fare to the Tottenham Court Road end of Oxford Street, and from there it was a short walk to the art shop in Rathbone Place. She must make haste – Violet Fabron would expect her gown to be finished well before curtain-up.

Nettie spotted a horse-drawn omnibus drawing to a halt in the Strand and she picked up her skirts and ran. The street was crowded with vehicles of all shapes and sizes, and with pedestrians milling about in a reckless manner, but this enabled Nettie to jump on board. As luck would have it, she found a vacant seat. One day, when she was rich, she would have her own carriage and she would sit back against velvet squabs, watching the rest of the population going about their business, but for now it was the rackety omnibus that bumped over the cobblestones and swayed from side to side like a ship on a stormy ocean, stopping to let passengers alight and taking on fresh human cargo. Steam rose from damp clothing, and the smell of wet wool and muddy boots combined with the sweat of humans and horseflesh. Nettie closed her mind to the rank odours and sat back, enjoying the freedom of being away from her cramped living quarters, if only for an hour or so.

Two hours later, Nettie returned home with the paints and two baked potatoes that she had purchased from a street vendor in Covent Garden.

Robert studied the small amount of change she had just given him. ‘The price of paint hasn’t gone up, has it?’

Nettie took off her bonnet and laid it on a chair in the living room. ‘No, Pa. I bought the potatoes because we need to eat. I’m so hungry that my stomach hurts.’

‘There should be more change than this.’

‘I had a cup of coffee, Pa. Surely you don’t begrudge me that?’

Robert shook his head. ‘No, of course not. I’m hungry, too. Thank you, dear.’ He took the potato and disappeared into his room.

Nettie sighed with relief as the door closed behind her father. She reached under her shawl and produced the new notebook that she had purchased in Oxford Street. It had cost every penny that she had earned from mending a tear in Monsieur Fabron’s best shirt, and she had supplemented it with a threepenny bit from the coins that her father had given her for his art supplies. Perhaps she should have spent the threepence on food, but she considered it money well spent, and paper, pen and ink were her only extravagance. Writing a romantic novel was more than a guilty pleasure; Nettie had been working on her story for over a year, and she hoped one day to see it published. But she dare not reveal the truth to Pa – he would tell her that she was wasting valuable time. No one in their right mind would want to pay good money for a work written by a twenty-year-old girl with very little experience of life and love. She knew exactly what Pa thought about ‘penny dreadfuls’ and he would be mortified if he thought that his daughter aspired to write popular fiction. It was her secret and she had told nobody, not even Byron or Pip, and Ted could not keep a secret to save his life. Poor Ted was still nursing a broken heart after being jilted by the young woman who worked in the nearby bakery; he wore black and had grown his hair long in the hope that he looked like a poet with a tragic past. Nettie had met the love of his life, Pearl Biggs, just the once, and that was enough to convince her that Ted was better off remaining a bachelor than tied to a woman who was no better than she should be.

Nettie hid the new notebook, along with two others already filled, beneath the cushions on the sofa, where she slept each night. She was in the middle of her story, and the characters played out their lives in her imagination while she went about her daily chores. Sometimes they intruded in her thoughts when she was least expecting it, but occasionally they refused to co-operate and she found herself with her pen poised and nothing to say.

She put the potato on a clean plate and went to sit on a chair in the window to enjoy the hot buttery flesh and the crisp outer skin, licking her fingers after each tasty bite. When she had eaten the last tiny morsel, she wiped her hands on a napkin and picked up her sewing. She concentrated on Madame Fabron’s gown, using tiny stitches to ensure that the darn was barely visible. Having finished, she put on her outdoor things and wrapped the gown in a length of butter muslin. She opened the door to her father’s studio.

‘I’m off to the theatre, Pa.’

‘The theatre?’

‘Yes, Pa. You remember, Madame Fabron needs her gown for the performance this evening.’

‘Oh, that. Yes, I do. Wretched woman thinks she can act. I’ve seen more talented performing horses. Don’t be long, Nettie. I want you to take a message to Duke. You’ll need to make full use of your feminine wiles because this painting won’t be finished today. He can come and view it, if he so wishes.’

‘Yes, Pa. I’ll be as quick as I can.’

Once again, Nettie left their rooms and made her way downstairs. She was tiptoeing past the Lorimers’ door when it opened and Biddy leaped out at her.

‘I heard you coming. I need help, Nettie. Mrs Lorimer’s having one of her funny turns.’

‘I’m sorry, Biddy. But I’m in a hurry.’

Biddy clutched Nettie’s arm. ‘Oh, please. I dunno what to do. She’s weeping and throwing things. I’m scared to death.’

‘All right, but I can only spare a couple of minutes.’ Nettie stepped inside the dark hallway and Biddy rushed past her to open the sitting-room door. The curtains were drawn and a fire burned in the grate, creating a fug. The smell of sickness lingered in the air. It took Nettie a moment to accustom her eyes to the gloom, but she could see Josephine Lorimer’s prostate figure on a chaise longue in front of the fire. She had one arm flung over her face and the other hanging limp over the side of the couch. Unearthly keening issued from her pale lips.

‘What’s the matter, Mrs Lorimer?’

Josephine moved her arm away from her face. ‘Who is it?’

‘It’s me, Nettie Carroll from upstairs. Biddy says you are unwell.’

‘I’m very ill. I think I’m dying and nobody cares.’

Nettie laid her hand on Josephine’s forehead, which was clammy but cool. ‘You don’t appear to have a fever. Perhaps if you sit up and try to keep calm you might feel better.’

‘How can I be calm when I am all alone in this dark room?’

Biddy shrank back into the shadows. ‘Is she dying?’

Nettie walked over to the window and drew the curtains, allowing a shaft of pale sunlight to filter in through the grimy windowpanes. ‘Mrs Lorimer would be better for a cup of tea and something to eat, Biddy. Have you anything prepared for her luncheon?’