По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

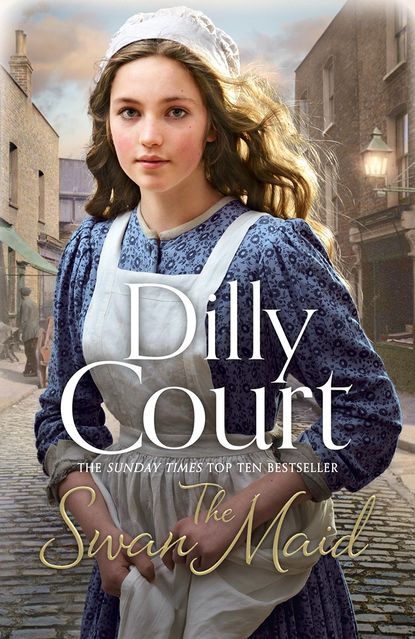

The Swan Maid

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Even so, Lottie had discovered a different side to Jezebel. Not long after the cook had started work at the inn, a small mongrel terrier had got in the way of one of the mail coach horses. The poor creature had been flung up in the air and had landed on the cobblestones in a pathetic heap. Jezebel had happened to be in the yard, smoking her clay pipe, when the accident occurred, and Lottie had seen her rush to the animal’s aid. She had picked it up and, cradling it in her arms like a baby, carried it into the kitchen. Lottie had followed, offering to help and had watched Jezebel examining the tiny body for broken bones with the skill of an experienced surgeon, and the tenderness of a mother caring for her child.

Despite two broken ribs and several deep cuts, Lad – as Jezebel named him – survived, and they became inseparable, despite Mrs Filby’s attempts to banish the dog from the kitchen, or any part of the building other than the stables. Lad, quite naturally, had developed a deep distrust of horses and he refused to be parted from his saviour. Jezebel, who was a good cook and worked for next to nothing, was the one person Mrs Filby treated with a certain amount of restraint and respect, and Lad was allowed to stay.

Lottie entered the kitchen and received an enthusiastic greeting from the small dog, who seemed to remember that she was one of the first people who had shown him any kindness. Having been flea-ridden and undernourished when he first arrived, he was now plump and lively, with a shiny white coat and comical brown patches over one eye and the tip of one ear.

‘Where’ve you been?’ Jezebel demanded. ‘The bullock’s head is done and the meat needs to be taken off the bone, and the vegetables need preparing to go in the stew. I’ve been run off me feet. I was better off in The Steel than I am here.’

‘I would have come sooner, but I had to wait on in the dining parlour and I hadn’t finished the bedchambers, but I’m here now.’

‘And where are those two flibbertigibbets? I suppose they’re making sheep’s eyes at that fellow Trotter. My Bill was just like him until I spoiled his beauty with my chiv. Trotter had best look out, that’s all I can say.’

Lottie lifted the heavy saucepan off the range. She knew better than to argue the point with Jezebel. It was easier and safer to keep her mouth shut and get on with her work; that way the long days passed without unpleasantness and everyone was happy in his or her own way. She had learned long ago that it was pointless to bemoan the fate that had brought her to The Swan with Two Necks. Born into an army family, her early years had been spent in India, and when her mother died of a fever, which also took Lottie’s younger brothers and sister, she had been sent to England with a family who were returning on leave, and left with her Uncle Sefton in Clerkenwell. A confirmed bachelor, he had little time for children and Lottie had been packed off to boarding school, although her uncle had made it plain that he considered educating females to be a total waste of money.

She had received a basic education until the age of twelve, when she returned home to find that her uncle had married a rich widow. Lottie’s childhood had ended when her new aunt, supposedly acting with her niece’s best interests at heart, had sent Lottie to work for the Filbys. It was just another form of slavery: she worked from the moment she rose in the morning until late at night, when she fell exhausted into her bed.

‘Are you doing what I told you, or are you daydreaming again, Lottie Lane? D’you want to feel the back of my hand, girl?’ Jezebel reared up in front of Lottie, bringing her back to the present with a start.

‘Sorry, ma’am.’

‘Get on with it, or you’ll get another clout round the head, and I ain’t as gentle as the missis.’ Jezebel stomped out into the yard, snatching up her pipe and tobacco pouch on the way. Lad trotted at her heels, growling and baring his teeth at the horses.

Lottie set to work and dissected the head, taking care not to waste a scrap of meat. Mrs Filby would check the bones later, and woe betide her if there was any waste. Parsimonious to the last, Prudence Filby ruled her empire with a rod of iron.

Minutes later, Jezebel marched back into the room. ‘Where’s Jem? The butcher has delivered the mutton. I want the carcass boned and ready for the pot. Go and find him, girl.’

‘But I haven’t finished what I’m doing.’

Jezebel moved with the speed of a snake striking its prey. The sound of the slap echoed round the beamed kitchen, and Lottie clutched her hand to her cheek. ‘The bullock’s going nowhere, but you are. Find the boy and tell him to get started or I’ll be after him.’

Lottie found Jem in the taproom, serving ale to the newly arrived male passengers, while Mrs Filby shepherded the ladies to the dining parlour, where they would be plied with coffee, tea and toast, all of which were added onto the bill. Each day was the same, and everyone knew their part in the carefully choreographed routine designed to make the travellers part with their money in as short a time as possible. Jem had taken too long offloading the last coach and was now behindhand with his tasks. Normally cheerful and easy-going, he was looking flushed and flustered.

‘Cook wants you, Jem.’ Lottie took the pint mug from his hand. ‘I’ll finish up in here. There’s only minutes before the coach leaves.’

‘I suppose she’s in a foul mood, as usual.’

‘You’ll soon find out if you don’t hurry up.’ Lottie passed the mug of ale to a man seated at the nearest table. She had just finished serving when the call came for the passengers to board, and she heard the clatter of hoofs and the rumble of wheels as yet another mail coach pulled into the stable yard. She was relieved by Shem Filby, who escorted the new guests into the taproom, enabling her to hurry back to the kitchen to prepare the vegetables.

Early mornings were always hectic, and she was used to the rush, although by midday everyone was beginning to flag, but there was no time to rest. Private carriages made up most of their custom during the day. Filby was pleased to point out that some people preferred the convenience of being transported from door to door, a luxury not provided when travelling by train, and others feared that the speed reached by steam engines would have serious effects on their health. The railways, he said, would one day put them out of business, but that was a long way off, or so he hoped.

Lottie did not have time to worry about such matters. She alternated between the kitchen, the dining room and the bedchambers, as did Ruth and May. They met briefly at mealtimes, with rare moments of free time during the afternoon lull, and then there was dinner to be prepared and served. After everything was cleared away and the dishes were washed and dried, there were beds to be turned back and aired, using copper warming pans filled with live coals. The constant need to provide washing facilities necessitated regular trips from the kitchen to the bedrooms, carrying ewers of hot water, and there was always someone who wanted something extra. Lottie had been sent out to buy all manner of things, mainly for ladies on their travels who had forgotten to bring a hairbrush or a comb. Sometimes it was a bottle of laudanum for pain, or oil of cloves for toothache, and these were always needed as a matter of urgency. Lottie had once been sent out to purchase a gift for a man’s wife as he had forgotten her birthday. Sometimes guests tipped generously, while others gave nothing in return, not even a thank you.

The only time the girls had to chat was during the brief period before they fell asleep on their straw-filled palliasses, and even then they might be awakened at any hour of the night and called upon to serve travellers who stopped at the inn.

Such a call came in the early hours of the next morning. Lottie was in a deep sleep when she was shaken awake by Ruth. ‘Get up. We’re wanted in the kitchen.’

‘What’s the matter?’

‘Soldiers,’ Ruth said excitedly. ‘I leaned over the balustrade and saw their red jackets. I love a man in uniform. Come on, they’ll be in need of sustenance.’

Half asleep, Lottie made her way downstairs, still struggling with the buttons on her blouse.

The stable yard was illuminated by gaslight and filled with the sound of booted feet, the clatter of horses’ hoofs and men’s raised voices. Above them the night sky formed a dark canopy, creating a theatrical backdrop to the dramatic scene. An officer was issuing orders, and Shem Filby was standing in the midst of the chaos, bellowing instructions to the ostlers that seemed to countermand those given by the young lieutenant. It had become a competition to see whose voice was the loudest, and in the end it was Mrs Filby, wearing a dressing robe over her nightgown, whose strident tones were heard above all others.

‘Silence.’ She waded into their midst, seizing a young private by the collar and thrusting him out of her way. ‘Gentlemen, have a thought for our other guests.’ She faced the officer with a contemptuous curl of her lip. ‘You will be more comfortable in the dining parlour, sir. Ruth will show you the way.’

‘Thank you, ma’am.’ As meekly as a schoolboy caught scrumping apples, he followed Ruth into the building.

‘Take the men into the kitchen, May.’ Mrs Filby marched up to two soldiers who were supporting a comrade who appeared to be unconscious. ‘What’s the matter with him? Is he sick? If so, you can take him to hospital.’

The elder of the two privates stood to attention. ‘If you please, ma’am, he’s suffered a knock on the head. A cracked skull ain’t catching.’

‘I don’t need any of your cheek, soldier.’ Mrs Filby peered at the injured man. ‘Has he been drinking?’

‘Only Adam’s ale, ma’am. We’ve been working on the telegraph lines in the Strand for two days, but now we’re heading for Chatham, and then on to the Crimea. All he needs is a bed for the night and some tender care, such as would be given by a kind lady like yourself.’

‘Well, then, I’m sure we can do something for one of our brave men who will soon depart for battle.’ Mrs Filby spun round to face Lottie. ‘Take them to my parlour. See that they have everything they need.’

‘Yes’m.’ Lottie made a move towards the doorway. ‘This way, please, gents.’

‘One moment.’ The lieutenant had obviously had second thoughts and had returned. ‘I’m grateful for your help, ma’am, but I am in charge of my men. Private Ellis needs medical attention.’

‘What is your name, sir?’ Mrs Filby bristled visibly. ‘You are on my property now, not the battlefield.’

He doffed his shako with a bow and a flourish. ‘Lieutenant Farrell Gillingham, Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners, at your service.’

‘Well, Lieutenant Gillingham, if you wish to take your man to hospital, feel free to do so, but we cannot incur the expense of the doctor’s fees, unless, of course, you wish to stump up for them yourself.’

‘Perhaps we will wait until daylight, ma’am. If Ellis is not well enough to be moved, I’ll think again.’ Gillingham spoke in a tone that did not invite argument. He bowed smartly and followed Ruth into the building.

‘Go with the men, Lottie,’ Mrs Filby said in a low voice. ‘You’re a sensible girl, for the most part, anyway. See to their needs as best you can.’ She lowered her voice to a whisper. ‘But don’t make them too comfortable. Their sort don’t pay well.’ She glanced round the yard, which was empty except for the ostlers who were attending to the horses. ‘Filby, where are you? Speak to me.’

Lottie beckoned to the soldiers. ‘Let’s get the poor fellow inside.’

The Filbys’ parlour was dominated by a huge walnut chiffonier, upon which were set out Prudence Filby’s treasured china tea set and small ornaments that had no intrinsic value, but must surely have a meaning for her. Lottie knew each piece intimately, having had to dust them every day since her arrival at The Swan with Two Necks. For some reason best known to herself, Mrs Filby had made the cleaning of her private parlour Lottie’s responsibility, insisting that the hand-hooked rugs with vibrant floral designs had to be taken out into the yard and beaten daily, and the heavy crimson velvet curtains and portière had to be brushed free from dust and cobwebs at least once a week.

Lottie held the door open, and while the soldiers settled Private Ellis on the sofa she raked the glowing embers of the fire into life.

‘What happened to him?’ she asked.

The younger of the two men eyed her up and down. ‘What makes a pretty girl like you want to work in a place like this?’

‘I think we should send for the doctor.’ Lottie chose to ignore the compliment. ‘Your friend looks very poorly.’

‘You’ve got eyes the colour of the cornflowers in the fields at home,’ he said earnestly, ‘and hair the colour of ripe wheat. I never seen such a pretty face in all me born days.’

‘That’s enough of that, Frank. You’re a sapper, not a poet.’ The older man held his hand out to Lottie. ‘Private Joe Benson, miss. Don’t take no notice of my mate. He can’t help hisself when he meets a young lady.’

Lottie smiled. ‘I don’t mind being called pretty, but I still think that your friend looks very unwell.’