По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

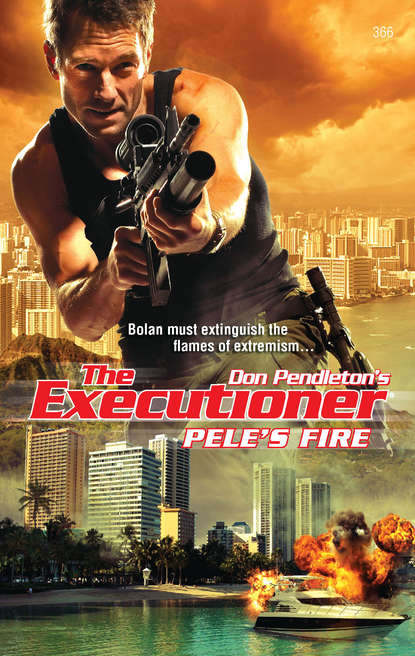

Pele's Fire

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“A home-rule group,” Bolan said.

“Home rule’s part of it,” Polunu said, “but we have groups like that all over. Talk and talk is all they do, until I’m sick of hearing it. Get off your flabby ass and do something, okay? Now, Pele’s Fire, they’re doers. Absolutely.”

“I’m aware of certain bombings, things along that line,” Bolan said.

“Sure. Why not? You haoles killed the red men and enslaved the blacks, then set them ‘free’ and segregated them until they couldn’t take a piss without permission from the government. Stole half of Mexico, and now you bitch about the ‘wetbacks’ sneaking back into their own homeland. Locked up the Nisei in the Big War, when they had no more connection to Japan than you do. All to steal their homes and land. Haoles need to take their lumps for a while. I still think that.”

“Which begs the question—”

“Right. Why did I split? Why am I here, right now, talking to you?”

“Exactly.”

“Haoles need a lesson, man. I still believe that. If they left the islands overnight, I wouldn’t miss a one of them. But getting rid of haoles doesn’t take some mass destruction deal, you know?”

“Not yet,” Bolan replied. “You haven’t told me what they’re planning.”

“That’s the thing, okay? I don’t know what they’re cooking up, exactly, but I’ve heard enough to know it’s too damned big. Like catastrophic big, okay? And not just for the haoles. Man, I’m talking wasteland, here.”

“That’s pretty vague,” Bolan said.

“Don’t I know it? When you start to hear this shit, you shrug it off at first, or you go along and say it’s cool. But when you start to ask around, like I did, for the details, they look at you like you’ve picked up the haole smell. Know what I mean?”

“I get the drift,” Bolan replied.

“So, when this friend of mine who brought me into Pele’s Fire comes up one day and tells me, ‘Polunu, Joey Lanakila thinks you might be working for the Man,’ I know it’s time to bail, okay? I got no future in the revolution, anymore.”

“So, all you have is talk about the outfit planning ‘something big’?”

“Not all. Did I say all?”

“If you’ve got any kind of lead for me, this is the time to spit it out,” Bolan said. “Or you can take it to your grave.”

“Is that a threat, haole?”

“No need. Your own guys want you dead. You want to play dumb, we can say goodbye right now, and you can take your chances on the street.”

“Hang on a minute. Shit! You heard about the missing haole sailors, I suppose?”

“Go on.”

“Six of them, I was told.”

“I’m listening.”

“They’re dead, okay? I give you that,” Polunu said. “I wasn’t in on it, but word still gets around. May turn up someday, maybe not, but Lanakila’s snatch squad got their uniforms. Don’t ask me why, because I’ve got no frigging clue. But something stinks.”

Bolan agreed with that assessment, but it still put him no closer to the solution of the riddle that confounded him. He clearly needed help that Polunu and his den mother could not provide.

“I need to make a call,” he said, clearly surprising both of them. “Five minutes, give or take, and then we’ll hatch a plan.”

He turned to Polunu, pierced him with a cold, steely glare. “If you’ve omitted anything, let’s have it now. Once we’re in motion, second-guessing’s not allowed and there’ll be no do-overs.”

“Man, I’ve told you everything I know.”

“Not yet,” Bolan replied with utter confidence. “When I get back, I’m going to ask for names and addresses. If you don’t have them, it’s aloha time.”

He took the satellite phone and the ignition key, and left them sitting in the dark.

Washington, D.C.

THE NATION’S CAPITAL lies six time zones east of Hawaii. When Japanese dive bombers attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, just before 8:00 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, 1941, most residents of Washington, D.C., were already digesting lunch.

It came as no surprise to Hal Brognola, then, when he was roused from restless sleep by a persistent buzzing, which he recognized immediately as his private hotline.

Scooping up the cordless phone, he took it with him as he left the bedroom, padding through the darkness and avoiding obstacles with the determined skill of one who’s done it countless times before.

“Brognola,” he announced, when he was halfway to the stairs.

“It’s me,” Bolan said.

“How’s the vacation going?”

“More heat than I expected right away, and heavy storms anticipated,” Bolan told him, speaking cagily despite the scrambler on Brognola’s telephone.

The big Fed got the message. “Are you dressed for it?”

“Not really. I may pick up an umbrella in the morning, if I find something I like. Meanwhile, there’s news from Cousin Polunu.”

“Oh?”

“He heard about the rowing team,” Bolan went on, “but doesn’t know where they’ve run off to. It’s a group thing, as suspected, but I can’t begin to guess when they’ll be back in town.”

“Staying away for good, you think?” Brognola asked.

“I’m guessing that’s affirmative.”

“And how does that impact your business on the island?”

“Still unknown. I’m thinking I should reach out to the locals. Find out what they have to say about it, when they’re motivated.”

“You think that’s wise?”

“Looks like the only way to go, right now,” Bolan replied.

“Well, you’re the expert,” Brognola replied. “I hope they’re willing to cooperate.”

“It’s all a matter of persuasion.”