По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

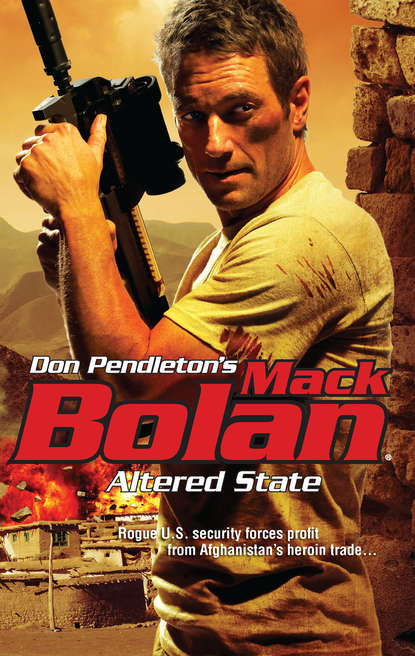

Altered State

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Looks like it,” Latimer agreed. “Listen, about before—”

“If you want to impress me, Russell, earn your pay.”

“I will.”

One of the guards stepped out, allowing Latimer to leave the car, and then the limousine rolled on, leaving the CIA’s deputy station chief to find his own way home.

Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan

J ALALABAD LIES ninety miles due east of Kabul, in Nangarhar Province, where small farmers have traditionally supported themselves by growing opium poppies. Recent claims suggested that production had been slashed by ninety-five percent, but Bolan knew that those statistics were skewed.

In fact, while many of the local growers had been driven out of business, large opium plantations thrived in the Cha-parhar, Khogyani and Shinwar districts.

Bolan was headed for Shinwar, with Deirdre Falk riding beside him and Edris Barialy in his now-traditional backseat observatory post.

“So, have you seen this farm before?” he asked her when they were a half hour from Kabul.

“Not the way I think you mean it, in the flesh,” she said. “We have a ton of photos at the office. Hidden camera, flyover, satellite, you name it. I can draw a map of it from memory, if that’s a help.”

Sending Falk back to her office for whatever maps or photographs they might have used, in Bolan’s view, had been too risky after their first clash with Vanguard warriors. He assumed the DEA office would be under surveillance, or might even have a paid-off mole inside who would, at the very least, tip off their enemies to Falk’s movements.

“Maybe later,” Bolan said.

In fact, he didn’t plan to hit the farm itself. At least, not yet. It would be covered by seven ways from Sunday by a troop of Vanguard mercs, most likely with the Afghan National Police or army on speed dial, in case the hired hands couldn’t cope with a particular emergency.

On top of which, Bolan was not equipped for razing crops in cultivated fields. He wasn’t armed with napalm or defoliants, and even if he had been, their delivery required aircraft.

“You’re after the refinery?” Falk asked him, frowning at the thought.

“I want to see it,” Bolan answered, “but it wouldn’t be my first move.”

He’d destroy more drugs by taking out a heroin refinery, along with whatever equipment Vanguard might have to replace after he blitzed the plant. That was part of his plan, but not the first move that he had in mind.

Falk shifted in her seat, plucking her damp blouse from her damper skin. Despite the small Toyota’s air-conditioning, the outside heat still made its presence felt with sunlight blazing through the windows, baking any skin it touched.

As with her office, Bolan had been forced to veto letting Falk go back to her apartment for fresh clothes or any other personal accessories. They’d done some hasty shopping back in Kabul, but he knew she wasn’t thrilled about the merchandise available.

“Feel free to share,” she said, a hint of irritation in her voice.

“They ship the heroin through Pakistan, correct?” he asked her.

“Right. It’s just a few miles farther east, and Nangarhar’s the next best thing to Pakistan, already. Most of the district uses Pakistani rupees when they pay their bills or bribes, instead of the official Afghanis. The provincial governor is kissing-close with Pakistan’s Intelligence Bureau.”

“And they move it how?”

“Depends on the size of the shipment. These days, most of the big loads roll by truck convoy.”

“Well, there you are.”

“I am?”

“A convoy isn’t fortified. It doesn’t have high walls or razor wire around it, and it’s not next door to a police station.”

“Aren’t you forgetting something? Like twenty-five or thirty shooters who’ll be guarding it?”

“I didn’t say it would be easy,” Bolan answered. “But it’s still our best shot for an opener.”

Grim faced, she said, “Okay. Give me the rest of it.”

United States Embassy, Kabul

A TWENTY-SOMETHING SECRETARY smiled at Russell Latimer and said, “The vice consul will see you now.”

The man from Langley thought about making some kind of smart-aleck remark, like James Bond in the movies, but his mood was too sour for levity. Instead of cracking wise, therefore, he gave the little redhead a low-wattage smile and moved past her, toward his contact’s inner sanctum.

“Come in, Russell! Come in!” his contact said, beaming. By that time, Latimer was in, closing the office door behind him. “Can I get you something? Coffee? Tea? A nice cold beer?”

“Scotch, if you have it, sir,” Latimer said.

“That bad, is it?”

Vice Consul Lee Hastings forced a chuckle. It reminded Latimer of dry bones rattling in a wooden cup. And yes, he’d heard that very noise some years ago while visiting a village in Angola.

“It’s bad, all right,” he said before thanking his host for the drink and tossing it down in one gulp. “I can’t say how bad, at the moment, but it has fubar potential.”

“Come again?”

“ Fubar . Fucked up beyond all recognition.”

The bony laugh again, as Hastings settled into his chair behind a standard-issue foreign service desk.

“In that case,” Hastings said, “I guess you’d better fill me in.”

Hastings was in his late forties, losing the battle of the bulge around his waist, but otherwise in decent shape for an American who’d spent the past three years in Kabul, fixing cracks and pinholes in the diplomatic dike and listening to bomb blasts in the streets outside. Latimer saw him slip one hand beneath the desk and knew that everything they said from that point on would be recorded, which was fine. He’d worn a wire, himself, prepared as always for the day when one of his superiors might try to sacrifice him for some personal advantage.

He began the briefing with a question. “Have you heard about the shootings in the Old City and Chindawol this afternoon?”

“Not yet,” Hastings replied. “Anything serious?”

“Eleven dead, sir,” Latimer informed him, giving Carlisle credit in advance for silencing his wounded soldier in the hospital.

“That’s most unfortunate, of course, but—”

“Sir, it’s not the number I’m concerned about,” Latimer interrupted. “It’s who they were.”

“I see. And who were they?”

“Vanguard employees. One from stateside, that I’m sure of, and the rest natives.”