По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

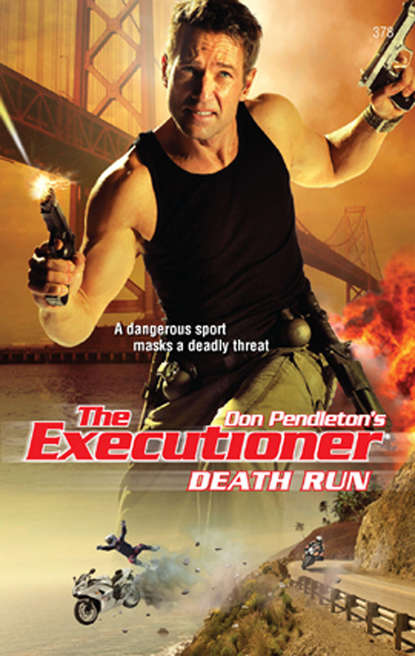

Death Run

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As he brought his bike up to speed and warmed up his tires, none of this mattered; he was just happy to be out on the track, tearing it up with his brother Eddie under the hot desert sun.

Eddie Anderson rose through the ranks of motorcycle racing in the United States to become the youngest person ever to win a national Superbike championship. His performance earned the young phenomenon a spot on the Ducati Marlboro MotoGP team. After winning rookie of the year in his first season, Eddie had a good chance of taking the championship this season.

Darrick circled the track, knocking a few tenths of a second off his lap times with each revolution of the fast circuit. The machine beneath him felt good, better than he’d expected. He skimmed his knees on the apron as he apexed the last corner on the track, straightened the bike and exited hard onto the front straight. He nearly jumped off his saddle when he felt a hand slap his ass. Darrick looked out of the left side of his helmet and saw Eddie passing him. Darrick could keep up with Eddie in the corners, but Eddie’s powerful bike ran away from Darrick’s as they rode down the long front straight. Eddie gained several bike lengths on Darrick before he threw his bike into Turn One.

There was a time when being passed would have thrown Darrick into spasms of rage, but seeing Eddie ride, watching him display his amazing skill and grace, made Darrick smile. He looked forward to his brother taking the number-one plate. Darrick pushed his bike to its very limits and beyond, not because he wanted to beat Eddie, but because he wanted to keep his brother in sight and watch him ride.

Darrick did a good job keeping up with his hard-charging brother, but the harder he pushed, the worse his bike behaved. The front end started to chatter under braking and continued to get worse until the bike was nearly in a tank slapper, forcing him into the paddock to have his technicians sort out the suspension. He pulled into the Free Flow pit, handed his bike to one of the technicians, peeled the top of his one-piece leathers to his waist, and went into the garage to find his team manager and explain the suspension problem. It would probably take only minor adjustments to dial out the front-end chatter and he wanted to get back out on the track before the two-hour practice session ended. He knew there was little point in trying to communicate the problem to the non-English-speaking technician.

It was early Friday morning and the paddock was quiet. The other racers were just starting to trickle out on the track, and a few teams hadn’t even completely set up in their garages yet. Within the hour the sleepy paddock would transform into a buzzing industrial worksite. It would remain so until long after the traffic jam that would inevitably followed Sunday’s race dissipated.

Darrick walked through the garage toward the office to find Jameed Botros, his team manager. He hated to complain because he didn’t want anyone to think he’d fallen back into his prima donna ways, but Botros always set him on edge. There was something wrong with the man, and with the entire Free Flow team itself.

Free Flow, a Malaysian motorcycle company that specialized in building scooters and small motorcycles for Third World markets, had begun developing larger motorcycles for the lucrative U.S. and European markets. Free Flow’s MotoGP race team was part of an effort to build brand recognition in those markets. Though the team was headquartered in Malaysia, most of the technicians and mechanics were Saudis, and none of them spoke English except Botros. Given that the Free Flow team’s primary sponsor was a Saudi oil company, it made sense that the team was composed exclusively of Saudis.

It didn’t bother Darrick that they were Saudis; what bothered him was that they were hard men who seemed out of place in the MotoGP world. They didn’t seem to like motorcycles or motorcycle racing all that much. They didn’t seem to like much else, either, especially Darrick. He’d never worked with such grim, humorless men.

Darrick walked into the office to find Botros speaking with a uniformed member of the Qatar security force. Because of the background noise from the activity in the garage, Botros and the security officer didn’t notice Darrick enter the room. Botros continued to speak to the man in Arabic. Darrick had picked up enough of the language to recognize the words package and shipment. He also made out the English names San Francisco and Mazda Raceway in the snippet of conversation he overheard. The fact that Botros was discussing the following week’s race at the Mazda Raceway near Monterey, California, with a member of the Qatar security force struck Darrick as odd, and his face betrayed his concern.

Darrick said, “Samehni,” Arabic for “pardon me,” one of the phrases he’d picked up. Botros glared at him and said nothing. Darrick switched to English and explained the front-end chatter to Botros, who promised to have a technician make the changes Darrick suggested.

Darrick retired to his motor home to freshen up while the bike was being prepared. When he returned to the garage for the last part of the morning practice session, a particularly humorless technician, a Saudi Darrick hadn’t met before, had his bike running and ready to go out on track. With his heavily scarred face, the man looked more like an escapee from a harsh prison than a trained motorcycle mechanic. “Your motorcycle is ready, sir,” the man said.

Astonished to hear the brutish man speak English, Darrick thanked him, then donned his helmet and gloves and rode out of the garage. He got out on track just as Eddie flew by at full throttle. Darrick knew he should let his tires warm up a bit, but he couldn’t resist the urge to chase his brother. He accelerated hard down the front straight, sat up to get into position for the first turn, and grabbed a handful of brake. Instead of pushing the brake pads into the discs, the brake lever went soft and pulled all the way back to the clip-on handlebar. A mist of brake fluid shot up inside his helmet, numbing his lips and stinging his eyes. His brake line had come loose from the reservoir on the handlebar. Riding nearly two hundred miles per hour into Turn One, he had no brakes.

Darrick leaned the bike into the turn and the front wheel lost traction, throwing the motorcycle to the pavement, shattering Darrick’s collarbone. He skidded off the track alongside the motorcycle and hit the gravel at the outside apex of the turn. In most crashes his protective gear would save him from serious injury, but no gear on Earth would help him if he hit the wall at that speed.

He tried to slow himself, but when he saw the clip-on handlebar of the motorcycle dig into the gravel and launch the machine skyward, he knew it no longer mattered. The bike flew twenty feet in the air and Darrick watched as it started to come down at him. He tried to roll onto his side even though he knew it would make him go airborne and flop around like a rag doll in a tornado. As he expected, his broken shoulder caught in the gravel and flipped him over, launching him feet first into the air. Before he could make an entire revolution, which would have jammed his head into the gravel and snapped his neck, the motorcycle came down across his chest. Man and machine hit the wall as one, crushing the life from Darrick’s body. His last thought before impact was that he was never going to see his brother win the MotoGP championship.

1

Mack Bolan crouched behind the cargo container in the Doha Industrial Area, watching the Qatar security force officer walk past on his rounds. Bolan had timed the man’s route and knew he had just short of thirty minutes to examine the shipping containers that had been transferred from the Pakistani container ship Hammam.

The previous night the soldier had slipped aboard the ship while it was anchored in the Doha Port and located the containers identified as his targets. He hadn’t had time to examine the containers, which were covered in blue tarps. However, he managed to place an electronic tracking device under one of the tarps before he had to clear off the ship.

That morning, he’d followed the trucks hauling the ship’s cargo to the warehouse. He’d located the cargo containers with a hand-held tracking unit disguised as a cellular phone and followed the signal to the corner of the warehouse. The crates were still covered with blue tarps.

When the security officer left the warehouse, the Executioner unfastened the tie-downs securing the blue tarp and pulled the back corner aside, revealing a rear hatch locked down tight by a high-security hardened steel padlock with a hardened steel shackle. It would take more than his .44 Magnum Desert Eagle to blast through that lock, but it didn’t matter. He couldn’t use a gun in the warehouse without alerting the guard, not even his sound-suppressed Beretta 93-R.

Bolan pulled the blue tarp back to reveal a red-and-yellow paint scheme. A painting of a blue racing motorcycle adorned the side of the container. He pulled the tarp farther back to reveal the words Free Flow Racing emblazoned on the bike’s fairing. It wasn’t what the soldier expected to see. According to the intel he’d received from Aaron “the Bear” Kurtzman, these containers held the ten kilograms of weapon-grade plutonium that disappeared in Pakistan the previous week. That was enough of the dense substance to build a nuclear bomb capable of destroying an entire city.

The president of the United States had ordered Hal Brognola, Director of the Justice Department’s Special Operations Group, to get the plutonium back. Because sources indicated that the material had gone to Qatar, getting it back would be a delicate task, given the close relationship between Qatar and the United States. Qatar, an independent emirate that jutted into the Persian Gulf—or Arab Gulf, as the locals called it—was one of the few remaining countries in the Middle East that welcomed U.S. military bases. Though the tiny emirate was politically stable thanks to its oil wealth, Qatar’s relatively moderate policies—it had been the first Arab nation to allow women to vote—made it a target for fanatical Islamic fundamentalists. The emir didn’t want to agitate the region’s radical factions by allowing the U.S. military to conduct an overt operation to retrieve the stolen plutonium so the Man asked Brognola to send in a discrete force. The big Fed assigned the task to the force of one known as the Executioner.

Because plutonium 239 is extremely toxic when inhaled or ingested—absorbing only a few micrograms causes cancer—destroying the ship would have been the equivalent of setting off a massive dirty bomb in the Doha Port, killing thousands of innocent Qatarians. Bolan had to find the material himself. He knew his job wouldn’t be easy. Though one of the most toxic substances ever created, plutonium 239 emits very little gamma radiation, making it virtually undetectable.

Because it ignites at room temperature when exposed to oxygen, plutonium 239 needs to be transported in a self-cooling container. Kurtzman discovered that a German firm had recently built an unusual type B container—a ductile iron cask with plumbing for coolant, a shock absorbing outer casing, and a nickel-lined interior coated with a synthetic resin that sealed in all radiation—that was small enough to fit in the back of a cargo van. The container had been shipped to a client in Pakistan. The only possible use for such a container would be the transport of nuclear material. When Kurtzman investigated the client, supposedly a Chinese energy research company, it turned out to be nothing more than a post office box in Grand Cayman.

The same source that alerted U.S. intelligence to the theft of the plutonium believed the material had been transported to the Port of Karachi, where it would be shipped to Qatar. The Bear’s team hit their computers and tracked every cargo shipment leaving Pakistan for Qatar. The manifest of one vessel, the container ship Hammam, contained anomalies that caught the attention of Stony Man’s cyberdetectives, convincing Kurtzman that this was their ship. Now Bolan stood before the containers that the team had identified.

The Executioner didn’t hear anything behind him but suddenly sensed the pair of eyes boring into him from behind. Instinctively, he threw himself forward and rolled over on his shoulder to see the security officer lining him up in the sights of a Heckler & Koch MP-5. Bolan flattened himself against the concrete floor and felt the initial volley of bullets skim over the top of his head. As the security guard fired, the muzzle rise made his trajectory climb, giving Bolan room to scramble behind the container.

If he’d been going up against an outlaw or terrorist, Bolan would have simply killed the man shooting at him. But the Executioner didn’t want to kill law enforcement officers, whether they were U.S. cops or members of Qatar’s national security force. He’d have to find another way out of this predicament, one that didn’t involve using his own guns.

He pushed his foot into the blue canvas and gained a foothold on one of the metal support ribs that ran the length of the cargo container. With a kick, he propelled himself high enough to grab the top of the container, and with the grace of a gymnast, he swung himself onto the top of the container. Because the security officer had still been firing his weapon, he hadn’t heard Bolan land atop the container.

When the shooting stopped, Bolan raised his head just enough to catch a glimpse of the officer. The greasepaint on the soldier’s face made him hard to see in the dark warehouse, but his blacksuit wasn’t providing much camouflage against the blue tarp. Bolan watched the officer creep toward the wall, where he could see behind the container. When he looked up, he’d see Bolan on top of it. The soldier grabbed an M-84 flashbang grenade from the vest he wore over his blacksuit, pulled the pin and lobbed the grenade over the edge of the container toward the officer.

The man spotted the motion and fired at Bolan. He only got off one round before the flashbang detonated, but that round struck the soldier square in the chest. He wore a vest containing an experimental lightweight armor that John “Cowboy” Kissinger had developed back at Stony Man Farm. The weapons specialist claimed this thin, flexible armor could stop anything up to and including a standard 7.62 mm round, though he wasn’t sure about high-velocity armor-piercing rounds. Fortunately it was capable of stopping the 9 mm round from the officer’s machine pistol, though the bullet struck the Executioner with enough force to knock him over the edge of the container.

Still in midair when the flashbang went off, Bolan covered his ears, closed his eyes and let out a shriek to equalize the pressure in his lungs. He landed on his feet, his legs pumping as soon as they hit the ground. The security officer would recover from the flashbang, but not before Bolan slipped back into the vent through which he’d entered the building.

Doha was a quiet city, and if the shots that the officer fired didn’t bring nearly all eight thousand men of the Qatar security force to the warehouse, the flashbang’s explosion certainly would.

The Executioner moved the grate covering the vent pipe aside, slid inside, replaced the grate and climbed up the pipe. When he got to the top of the vent, he crawled through the rectangular vent pipe that ran along the roof toward a blower fan until he reached the hole he’d cut in the bottom of the pipe. There was only about eighteen inches between the pipe and the roof of the warehouse so he had to snake his way out of the pipe. He could see flashing blue lights from the security force vehicles driving toward the front of the warehouse. Bolan ran to the back edge of the roof where he’d left the rope he’d used to climb up and clipped his descender to the rope. He let himself down the side of the building as fast as he could without breaking any bones. Upon hitting the ground, he ran toward the hole he’d cut in the security fence on his way into the warehouse facility. He was in his Range Rover and driving back toward his hotel before the security officers even discovered he’d left the building.

Bolan was grateful that he hadn’t injured any of the officers who kept the peace in the tiny emirate. Qatar’s security force had a reputation for being good cops, honest and reasonable men who had never been charged with a human rights violation.

He hadn’t been so lucky; he was pretty sure he’d broken a rib when he took the round from the officer’s MP-5, but he’d survive. He hadn’t located the plutonium, but at least he had a lead: Free Flow Racing. He knew that the Losail circuit in Doha would be hosting Grand Prix motorcycle races that weekend. He wouldn’t be able to get back in the warehouse after the fiasco that had just occurred, but at least he knew where to look.

First, he’d have to find a reason to be at the race. He drove back to his hotel and dialed the secure number for Stony Man Farm on his cell phone. It took a few moments for the signal to travel its circuitous but untraceable route before he heard Kurtzman on the line. “What’s up, Striker?” Kurtzman asked, using Bolan’s Stony Man code name.

“I need to be someone else,” Bolan replied.

“Anyone in particular?”

“I’d kind of like to try an average Joe, but maybe another time. Right now I need to be a salesman.”

POSING AS MATT COOPER, Bolan presented his credentials to the paddock guard. Overnight Kurtzman had created a background for Cooper, an American sales rep for the racing fuels division of CCP Petroleum, a Russian company created from the ashes of the failed Yukos Oil. Cooper’s assignment was to get MotoGP racing teams to use CCP racing fuel. To create the character of Cooper, Bolan, who spoke decent Russian, spent the night studying the recent history of Grand Prix motorcycle racing.

The Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) formed the MotoGP class, motorcycle racing’s most prestigious racing series, for the 2002 season. Originally FIM had dictated that 990 cc four-strokes raced in the class. When those motorcycles became so powerful that their performance outpaced the limits of tire technology, the FIM lowered the displacement limit to 800 cc for the 2007 racing season.

Darrick Anderson, an American rider, dominated the first three seasons of MotoGP, but problems with alcohol and other drugs had destroyed his career. He’d disappeared for several years, but this year he was back. Bolan had Darrick’s name at the top of the list of people he planned to interview, since Darrick was Free Flow Racing’s top rider.

Posing as Cooper’s assistant at CCP’s American branch, Barbara Price, Stony Man’s mission controller, had arranged meetings with representatives from several MotoGP teams. Most top teams were already supported by major oil companies so the story was that CCP targeted smaller teams. Since MotoGP teams didn’t get any smaller than Free Flow Racing, it only made sense that Cooper would meet with them first. Price set up a meeting with Team Free Flow Racing’s general manager Jameed Botros.

Bolan arrived at the Free Flow Racing garage complex in the Losail paddock fifteen minutes before his scheduled meeting with Mr. Botros but found the area deserted. The doors were open, so he let himself inside, hoping to find out where everyone was, but the garages were empty. The Executioner walked toward a wall covered with television monitors and realized why the complex was empty. From several different angles the monitors showed Darrick Anderson’s lifeless body being loaded onto a helicopter. Bolan could tell things didn’t look good for Mr. Anderson.

He looked around the building and saw several containers identical to the ones he’d seen in the warehouse the previous night. He activated the GPS locator in his cell phone and saw that the container he wanted had to be either in the very back of the garage complex or behind it. He made his way to the rear of the complex without finding the container.

He punched a button that opened one of the overhead doors in the back wall and went outside, where he found the container he’d tagged with the homing device still secured to the bed of a truck trailer. He examined it and saw that the seals applied to the container in Pakistan still hadn’t been broken.

Bolan turned around and found himself face-to-face with a man dressed as a member of the Qatar security force, though the dagger in his hand was not standard-issue for the force. Bolan hadn’t heard the man approach because of the noise generated by the barely muffled motorcycle engines that permeated the entire Losail facility. The officer lunged at Bolan with the dagger, its tip contacting Bolan’s rib cage just below his left armpit. Because the Executioner had moved back the moment he saw the blade coming at him, the dagger barely penetrated his skin.

Bolan brought his left elbow down on the attacker’s arm, snapping both the radius and ulna bones in his forearm. The man fell beneath the force of the blow. Bolan reached around with his right hand and caught the knife as it fell from the attacker’s disabled hand. The man lunged forward and in an instinctive reaction Bolan sliced upward with the knife, catching the man several inches below the navel and cutting all the way up to his rib cage.

The man staggered backward and fell, clutching his midsection in a failed attempt to hold in the intestines that poured from his eviscerated abdomen. Bolan knew this man most likely was not a cop. Cops didn’t try to assassinate strangers with daggers, especially Qatar’s security force officers. He was certain that the man he’d just gutted was a criminal posing as a security officer.

Bolan pulled his Beretta from his shoulder holster and asked the man, who was dying too slowly to avoid intense suffering, “Do you speak English?” He received no answer. The man had entered a state of shock and wasn’t able to respond. Bolan estimated he would be dead within minutes.